Your Personal Secrets May Be Written All Over Your Face

Facial recognition technology offers enormous promise in medicine, security and consumer applications, but concerns about privacy and abuse also bear examination

09:1705.04.18

Human facial expressions are determined by a complex array of muscles signaling to others a person’s ethnic background, age, gender or mood. Even a slight movement of a facial muscle allows us to guess what a person is feeling or what they are about to say. In the past few years, artificial intelligence technologies have taken this basic human ability a few steps forward and are now capable of not only recognizing a certain individual but of deriving far-reaching insights about them, which they may have prefered to keep secret, or are not even aware of themselves, such as sexual orientation or violent tendencies. The technologies are fast, accurate and widely available, often as off-the-shelf products requiring little to no adjustments for in-depth facial analysis.

Galit Wellner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Galit Wellner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Tal Hassner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Tal Hassner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Michal Kosinski. Photo: Lauren Bamford

Michal Kosinski. Photo: Lauren Bamford

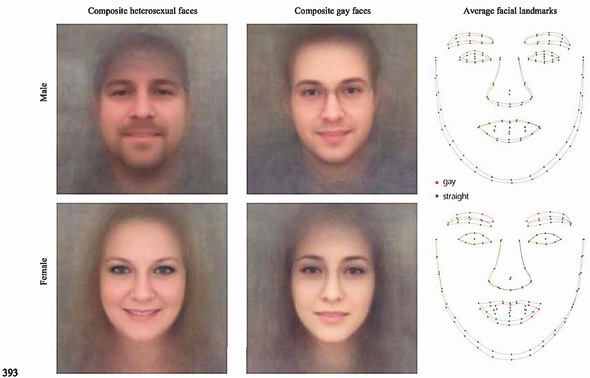

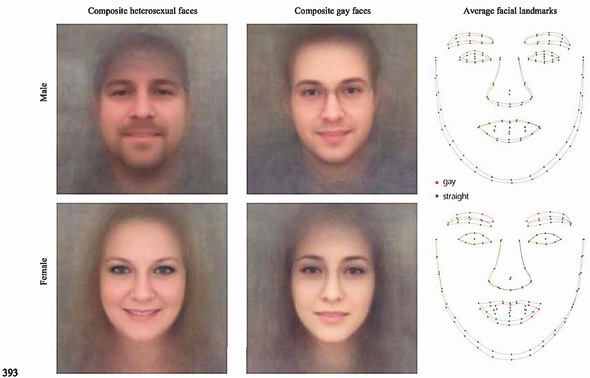

Excerpt from Mr. Kosinski's research on identifying sexual orientation

Excerpt from Mr. Kosinski's research on identifying sexual orientation

A facial recognition payment station by Alipay. Photo: AFP The European Union is currently promoting legislation giving each person full ownership of their biometric data and the right to decide how it can be used. Such laws, however, neglect to take into account the public’s willingness to freely give out their data to companies in exchange for services. In addition, this discussion becomes more acute as we turn our eyes to some of the less democratic countries such as China, Russia, and Iran, where the government is actively using technology to persecute people opposing the regime and control every move made by its citizens.

A facial recognition payment station by Alipay. Photo: AFP The European Union is currently promoting legislation giving each person full ownership of their biometric data and the right to decide how it can be used. Such laws, however, neglect to take into account the public’s willingness to freely give out their data to companies in exchange for services. In addition, this discussion becomes more acute as we turn our eyes to some of the less democratic countries such as China, Russia, and Iran, where the government is actively using technology to persecute people opposing the regime and control every move made by its citizens.

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

The facial recognition revolution is already here in the form of cheap high-resolution security cameras installed at every street corner, as well as standard consumer products found in almost every person’s pocket, with such technologies as the iPhone X’s Face ID feature. Despite benefits in the fields of security, medicine, and user experience, concerns are being raised when it comes to privacy and potential misuse of these technologies.

Galit Wellner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Galit Wellner. Photo: Orel Cohen New technologies are always received with mixed feelings, Galit Wellner, a philosophy of technology researcher at Tel Aviv University and the NB Haifa School of Design, said in an interview with Calcalist. When industrial machines appeared in the late 19th century, some were happy about the more efficient and cost-effective way of producing things while others were wary of changes and possible loss of jobs, and tried to destroy the machines, she added. These two extremes will always be there, and the tension between them is healthy because it forces us to consider where the reasonable balance is, Ms. Wellner said.

Ms. Wellner sees facial recognition as a tool that can help remove barriers and save people the trouble of remembering passwords or making up new ones. “Everyone is talking about the Panopticon, about being a surveillance society, but I am not that concerned,” Ms. Wellner said, referring “I cannot sew as well as a sewing machine can, my handwriting is much less clear than typing and I type much faster than I am able to write manually. A lot of technologies help us do things better. Facial recognition is no different.” Ms. Wellner does, however, warn that a democratic society must create some boundaries to prevent misuse and notes she would want to know exactly what kind of information is being gathered on her, and what it is used for.

Twelve years ago computers were already better than humans at recognizing faces, but that was only when a person was trying to be recognized by standing directly in front of the camera and taking off glasses and accessories, says Tal Hassner, an associate professor at the Open University in Israel and a senior computer scientist at the University of Southern California. In recent years, Mr. Hassner’s research has focused on identifying a person’s age and gender with face recognition technologies.

Tal Hassner. Photo: Orel Cohen

Tal Hassner. Photo: Orel Cohen In 2007, deep learning technologies capable of recognizing people under less than optimal conditions—when they do not know they are being photographed, when they are far from the camera, or when their face is blurred or partially hidden—were starting to surface, Mr. Hassner said in an interview. This is done through an artificial neural network that is exposed to millions of faces and expressions and can also be trained to not only identify a person but also determine their age and mood, he added. The network’s ability to recognize and analyze faces is far superior to the human ability to do so, Mr. Hassner said.

Computers today are much better than people in almost any visual-cognition task, says Michal Kosinski, a psychologist and data researcher at Stanford University who recently gained some infamy when it was reported that data he collected was used by Cambridge Analytica in its campaigning for Donald Trump in 2016. In an interview with Calcalist, Mr. Kosinski said that computers are more effective in connecting numerous tiny signals that are insignificant in and of themselves, but add up so that an algorithm can examine them and make a very accurate analysis of a person’s personality and feelings.

In September, Mr. Kosinski published research claiming his algorithm can identify a person’s sexual orientation with 91% accuracy in men and 83% in women, just by analyzing their faces. Fearing controversy, Mr. Kosinski said he did not want to publish the results at first but decided to do so because companies and governments have been using photos of people’s faces for years in order to predict behavior and he decided it was important for people to know what kinds of information they can actually get.

Michal Kosinski. Photo: Lauren Bamford

Michal Kosinski. Photo: Lauren Bamford Mr. Kosinski also said technologies that can accurately guess a person’s political inclination are already under development. Just because people cannot determine who someone is going to vote for, what their personality traits are, or what they will do later, by looking at their face, does not mean the data is not there, it just means that the human mind is incapable of interpreting it, he said.

Useful technologies often inherently compromise users’ privacy and collect large amounts of data. There is no clear line separating beneficial technologies from harmful ones and even tools developed with the best intentions in mind can be used for entirely different purposes. Bellow are some applications of facial recognition technologies currently in use worldwide.

Excerpt from Mr. Kosinski's research on identifying sexual orientation

Excerpt from Mr. Kosinski's research on identifying sexual orientation Boston-headquartered company FDNA Inc. developed a system that uses facial recognition to identify rare underlying genetic medical conditions which a doctor may not be able to easily detect. Like Down syndrome, many conditions manifest in a person’s face, but it is impossible for a doctor to recognize conditions that are less common just by looking at the patient, Dekel Gelbman, CEO of FDNA, said in an interview. Another example of possible medical applications is a system developed by Tel Aviv-based Face-Six that uses facial recognition to eliminate the risk of giving medication to the wrong patient in a medical facility.

Facial recognition can also be used for personal comfort and security, for example, recognizing who has entered a room and adjusting the temperature or lighting conditions accordingly, or distinguishing between a house’s inhabitants and outside intruders. Law enforcement and government agencies can use facial recognition to identify criminals and terrorists or locate missing persons and as a substitute for biometric paper passports, a process currently underway in Australia. The FBI’s facial recognition system is capable of identifying people within a large crowd using a database of 411 million pictures of U.S. citizens. Estimated to include about half of the U.S. population, many of the individuals in the database are innocent civilians.

Some applications can turn people’s faces into a digital wallet. In China, KFC customers can use their Alipay account to pay for their meal, simply by smiling at a camera; in the U.K. two retailers already use facial recognition for confirming a customer’s age when purchasing alcohol as well as for quick checkout; some applications are capable of recognizing customers entering a store and immediately offering them customized deals and products based on data gathered from social networks, credit card history, and other public and private records.

A facial recognition payment station by Alipay. Photo: AFP

A facial recognition payment station by Alipay. Photo: AFP Related stories:

- Israel to Share New National Health Database with Local Tech Industry

- For Social Networks, Misuse of User Information is a Feature, Not a Bug

- Startup that Tricks Facial Recognition Algorithms Raises $4 Million

There is no way to hide from facial recognition algorithms, says Ido Naor, a senior researcher at Moscow-headquartered cybersecurity company AO Kaspersky Lab. You do not have to be present online for an algorithm to recognize your face, Mr. Naor said in an interview. “There are networks of cameras everywhere, and no matter where you are, a lens is going to capture you at some point,” he said.

“Facial recognition is like a hammer or a car,” Mr. Hassner said, “you can use them for wonderful things as well as terrible things.” That is true for any technology developed by man, he added. Mr. Kosinski agreed, adding that even if it were made illegal in one country, it would just be developed in another, because it is too useful for people and countries to ignore. “Facial recognition comes at the price of compromising privacy but not using it may cost human lives, personal welfare, and financial progress. I, for one, cannot say what is more important.”