Corporate Funds Are Taking Over Israel's Startup Scene

Israel has seen a record $7.5 billion invested in startups in 2018. Unlike previous years, corporate venture arms played a role in almost half of the year’s deals

13:3619.06.19

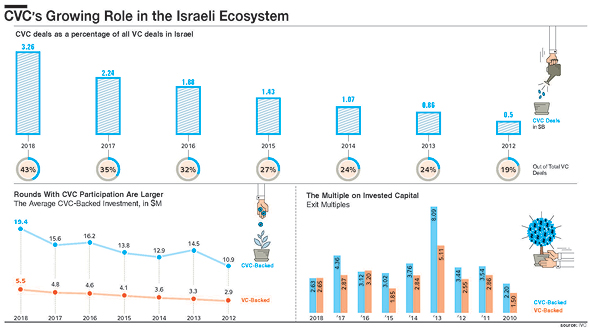

Israel has seen a record $7.5 billion raised by startups in 2018, according to data from Tel Aviv-based research firm IVC Research Center Ltd. Unlike previous years, almost half (43%) of all funding rounds were participated by at least one corporate venture capital (CVC) vehicle, or as entrepreneurs like to call them, strategic investors.

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

CVCs are not a new phenomenon, but their popularity has risen and ebbed according to market conditions. A 2016 report by research firm CB Insights that looked into the history of corporate funds found that at their peak, in the 1970s, they accounted for 41% of all venture capital investments. In recent years, they have peaked again, reaching a 51% market share in the U.S. in 2018, according to research company Pitchbook Data Inc.The same trend holds true for Israel, according to IVC. Between 2012 and 2018, CVCs’ share has risen from less than a quarter to 43%. In 2012, they were involved in 6% of the 773 deals recorded that year, while in 2018, that percentage rose to 18% out of 949 deals.

In January 2014, Google paid $3.2 billion for connected home company Nest Labs Inc., three years after backing the company via Google Ventures. The acquisition strengthened the conception that a CVC investment hints at the possibility of a future acquisition, but such cases are actually rare. While CVCs have become powerful players in global tech, the billions they funnel into the industry have complex repercussions for the entire financial system.

Venture capital funds aim to triple returns on investments over a period of five to 10 years, but most investments don't yield returns. Fund managers hope to make a killing off two or three companies out of a portfolio of 10-15 in order to meet investor expectations. The focus funds direct to conserving their investment can be seen in their investment contracts.

Dan Shamgar, partner at Israel-based law firm Meitar Liquornik Geva Leshem Tal. Photo: Tomer Jacobson

Dan Shamgar, partner at Israel-based law firm Meitar Liquornik Geva Leshem Tal. Photo: Tomer Jacobson

Funds put a lot of effort into clauses that protect their investment, for example, the question of rights if a startup is liquidated, Dan Shamgar, partner at Israel-based law firm Meitar Liquornik Geva Leshem Tal, told Calcalist in an interview.

CVCs, on the other hand, are less concerned with conserving the value of their investment, and more with influencing the company's operations and its technology in order to generate collaborations and learn of future business strategies, Shamgar said. CVCs usually only invest in startups that develop products the corporation deems relevant, he said, and therefore have agreements that pertain to products and development and not just financial elements.

CVC investments also almost always include a clause that requires startups to inform the corporation of all acquisition offers. This practice, Shamgar said, is meant to help CVCs keep updated on the market and the startup's attractiveness to other companies. "Acquisitions are usually discrete processes, and some investors feel like they missed an opportunity," he explained. While a startup that does not want to be acquired by its investor may find such a clause limiting, several offers usually boost the final acquisition price, he said.

Investments are usually not an indication of a future acquisition, Yair Shoham, the manager of Intel Capital Israel, said in an interview with Calcalist. "We almost never invest in chips but rather in technologies that are on the outskirts of Intel's core interests, to increase the range," he said. One example is Israeli public transit app developer Moovit App Global Ltd., which Shoham said supports the ecosystem of Intel-owned automotive chipmaker Mobileye. Another is blockchain startups, "because we believe the development of the domain will require stronger chips."

Yair Shoham, the manager of Intel Capital Israel. Photo: Amit Sha'al

Yair Shoham, the manager of Intel Capital Israel. Photo: Amit Sha'al

"For companies in which we think we might be interested to acquire in the future, we’ll ask for notice, but mostly we don't acquire portfolio companies," Shoham said. "And anyway, I believe that if Intel is a potential buyer, the startup will approach us."

Over the past decade, there has also been a change in the profile of the typical strategic investor. In the past, it was typically a company with its own research and development unit, which used its venture arm as a way of increasing market reach. Today, companies that don't traditionally perform internal R&D have joined the game. Financial institutions such as banks and insurance firms have venture arms, and so do media entities such as Disney and CNN.

The total annual investments of American CVCs grew from $6.4 billion in 2009 to over $39 billion in 2018, according to Pitchbook, and in certain domains that has set off a competition for startups, boosting their valuations. Developments in the automotive industry, for example, have pushed carmakers into hedging their bets across several tech companies at the same time: the Volkswagen Group invested in both Uber and Israeli taxi-hailing company Gett before starting its own ridesharing company, MOIA; General Motors invested in at least three mapping companies and acquired two more.

An investment from a corporate entity that operates in the same domain is not always a comfortable situation for a startup. "A strategic investor involved in the company's operations will perhaps learn information that the portfolio company isn't interested in sharing, especially if they target the same market," Shamgar said. Another difficulty might arise if the startup wants to do business with a rival of its strategic investor. Startups need to take into account their future plans when weighing the pros and cons of accepting an investment, he said.

On the other hand, strategic investors can provide young companies with a vote of confidence and open a lot of doors for them, Shamgar said—and not just technologically or in terms of courting partnerships.

Related stories:

- Venture Capital Firm Finistere Is Committed to Israel, Says Founding Partner

- As Market Matures, Israeli Tech Valuations Continue to Climb

- Intel Announces Israeli Startup Accelerator

According to IVC, on average, exists yielded higher returns for founders and investors if a CVC was one of the company's backers. Between 2010 and 2018, companies with CVC backers recorded higher multiples for every year except 2016.

Shoham thinks it is down to the added contribution CVCs make. Corporates have a much wider sphere of influence than any venture capital fund, he said. "We have 120,000 employees, of which a large number can be recruited to help the companies we invested in," he said. "Any venture capital fund would have been happy to invest in the companies we backed in 2018, but they came to us because we are Intel, and we can help them build their technology and market. It might be hard to enlist the business division to help companies, but when it works it works."