From Seinfeld to Black Mirror: film and TV serve as valuable academic teaching materials

As reality turns closer to dystopia and fiction grows ever more real, the use of copyrighted creative works for teaching various fields grows. With the now less-than-temporary shift towards distance learning outside the classroom, new legal implications arise

Dystopia is quickly becoming a reality, so it makes sense to see a demand for dystopian fiction. A recent Slate article pointed to the value of such fiction as both a warning of things to come, as well as a useful tool in planning for such eventualities.

This planning is valuable both practically, if and when the need arises, but also legally, in terms of plotting the ethical, social, and legal ramifications of said eventualities and figuring out what to do from a regulatory standpoint. Also, misery loves company and this seems to hold true even for fictional misery.

The younger crowd might, for example, consider the recently popular television anthology series Black Mirror, which first aired in 2011. Many of the show’s most disturbing episodes feature seemingly futuristic technologies that wire directly into the human brain and present the potential consequences thereof. Surprisingly, such revolutionary technologies are not so far off.

A great example of this convergence of fantastical fiction and fact is Elon Musk’s Neuralink Corp. On Wednesday, Musk announced a similar device to the one in Black Mirror, that would allow people to “listen to music” directly through Neuralink’s chips implanted in the user’s brain. Musk also suggested the chips “could help control hormone levels and use them to our advantage.”

Given the warp speed at which fiction and non-fiction appear to be colliding, there would seem to be clear teaching opportunities in employing dystopian film and television programs in higher education, especially in the areas of pedagogy focused on the intersection between law and technology.

This idea of using popular culture as a teaching tool is not novel per se and there are already a number of research articles focused on extracting educational value from Hollywood entertainment.

In fact, I know of at least one academic course in Israel (which I teach) that focuses on extracting topical and useful legal theory relating to entrepreneurship and intellectual property from the HBO hit comedy Silicon Valley (2014-2019).

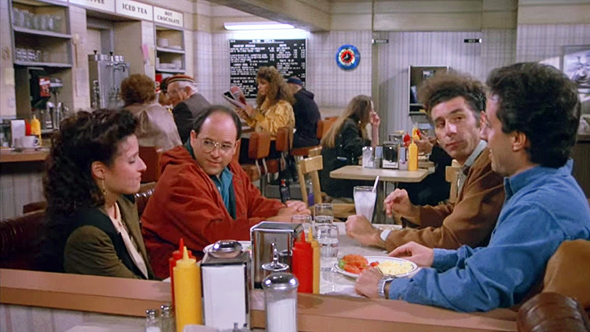

Notably, the use of film and television in legal education isn’t limited to technology issues. There is now even an online multi-institution law course, called Yada Yada Law School that is centered on the popular 1990s era Seinfeld television show.

It is likely that we will see more of these types of classes as the pandemic rages on and in-class discussions continue to be replaced by long-distance virtual classrooms. Student attention is hard enough to maintain under optimal classroom circumstances, let alone where it is easy for the student to occupy themselves with anything else on their computers— with Netflix or social media being the most common culprits—while still looking somewhat engaged via the low-resolution webcam. All while the hapless professor is struggling to adapt to the new teaching methods.

However, a class where the source material is popular culture might actually catch and hold students’ attention, while also teaching them timely and relevant information. Film and television in legal education provide additional important skills relating to issue spotting, that is, the ability to find actionable information within a sea of seemingly unrelated data.

But, be warned, calling some of these films and shows fiction is actually a bit misleading. Sure, the plots are contrived and the timescales are modified to fit within our limited attention spans, but a lot of modern film and television strives to create as realistic a fiction as possible, even buying real working machines and hiring technical advisors and consultants to make sure that the gobbledygook spouted by the actors makes sense to eggheads everywhere. Some television shows even donated their medically relevant stock to local hospitals as filming shut down and the number of patients went up due to the coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak. Thus, as more sectors of entertainment become truer to science and technology, they also become ever-more useful pedagogical tools as they more accurately reflect real-life circumstances and situations.

There are legal limitations, however, in using Hollywood to augment your teaching. According to U.S. copyright law, the unauthorized public display of a film or large portions thereof would, under normal circumstances, fall within the rubric of civil and criminal infringement. Fortunately for teachers, under U.S. code 17, section 110(1), it is not considered an infringement provided it was “in the course of face-to-face teaching activities of a nonprofit educational institution, in a classroom, or similar place devoted to instruction.” This does not, however, cover virtual teaching, made popular by the pandemic.

Fortunately, as discussed in a previous column, the forward-thinking and farsighted 2002 Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization Act (TEACH) expanded this loophole, albeit with many problematic caveats, to distance education as well.

In other jurisdictions, for example in the U.K., academic institutions may rely on fair dealings defenses in public presentations of film or via direct carved out limited exceptions in the law under section 34 of the country’s 1988 Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act. While the British law was subsequently amended to allow students to watch copyrighted films outside of the classroom for educational purposes, it still requires that access to copyrighted works be limited to dedicated terminals on university campuses. Also, these exceptions are not applicable for commercial purposes, meaning that once created, the instructor cannot sell versions of their course, nor can the university sell access on different or commercial platforms.

Canada, a commonwealth country, which owes much of its copyright law to the U.K., similarly has fair dealing exceptions for educators. Moreover, under Canadian copyright law, a professor can show publicly available online material to their students, provided the copyright holder has not expressly forbidden it.

Finally, under a simple reading of Israeli law, as per Section 29 of the 2007 Copyright Act, such exceptions to infringement are only allowed if the display of the copyrighted work is open only to the employees and students of the institution. The law does provide, however, additional post facto defenses for broader activities under the Israeli version of the fair use defense, through Section 19.

In light of these limited defenses and dodges, could a professor simply share their Netflix password with students so that everyone can access the required viewing in the non-public setting of their own home? Some have suggested that the major streaming networks would be blasé about this type of sharing, although Netflix indicated that it is looking for “consumer-friendly ways” to push back against the phenomenon.

Currently, as long as streaming companies do not expressly disallow it, however, users are likely not violating the U.S. Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, unless, the Supreme Court decides to interpret it differently over the summer.

If the law does narrow down copyright workarounds for professors, and access to film in e-learning and distance education is further limited, we can expect a further encroachment of this dystopian world: dreary and dull lectures.

Dov Greenbaum, JD PhD, is the director of the Zvi Meitar Institute for Legal Implications of Emerging Technologies and Professor at the Harry Radzyner Law School, both at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya.