Interview

“We’re lucky that the mutations only affected the rate of infection, they could have created a far more violent virus”

Prof. Ron Diskin, an expert on deadly viruses, isn’t worried that the new Covid-19 vaccine will lose its effectiveness but is concerned about millennials’ cavalier attitude toward the disease

Prof. Ron Diskin is an expert on deadly viruses at the Department of Structural Biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science and the winner of the 2020 Scientific Council Prize for Chemistry. One of the research projects that is being conducted in his lab at the moment is an attempt to develop a drug to treat those who have already been infected by Covid-19 (coronavirus) by creating a synthetic molecule that can bind to the virus, prevent it from infiltrating human cells, and can signal to the immune system that it must be attacked.

Over the past few weeks, scientists uncovered two new strains of the Covid-19 virus, the “British” mutation and the “South African” one, are there others out there?

“Yes, they are definitely not the only ones. Viruses are constantly changing, each one at its own pace. Both of those mutations popped up on the news because they infect people at a higher rate than the original strain. The South African variant is slightly more worrying, since it has altered a portion of the spike protein’s active site, (the change allows the virus to bind to cells more strongly, making infection easier) that the Covid-19 vaccine is designed to bind to, but it’s not the end of the world, since the vaccine can be modified.”

Prof. Ron Diskin of the Weizmann Institute of Science. Photo: Amit Shaal

Prof. Ron Diskin of the Weizmann Institute of Science. Photo: Amit Shaal

Do viruses have a “coefficient of variation” like in mathematics? Can we assume that out of every X number of infections, the virus will carry a certain mutation?

“Every virus has a unique mutation rate. In viruses of the SARS variety—including SARS-CoV-2 which is responsible for the coronavirus—every other infection event, on average, is characterized by some type of mutation to its genome. The most common type is ‘silent’ mutations, which occur at the viral genome level but don’t alter any of its proteins. Those types of mutations are a useful tool in contagion research: genetic sequencing of the virus allows us to track these genomic signatures and build an epidemiological ‘transmission tree.’”

And what happens when a mutation does change one of the virus’ proteins?

“Some of these mutations will kill the virus and cripple it, so that it can’t infect others, spread, or replicate itself. These mutations will disappear by way of elimination. However, a small part of them will be expressed at the viral protein level, but in such a way that we won’t notice.”

“Even rarer mutations are those that give the virus an extra oomph, and by the process of natural selection, they will become the majority of the viral population. The mutations that we mentioned earlier, for example, modify the spike protein in such a way that it improves the virus’ ability to bind to receptors on our human cells. This is what causes viruses that carry these mutations to be more effective at infecting people. From the virus’s perspective, these are more successful mutations.”

“Viruses will always change, especially RNA-viruses, like the SARS viruses. We’re lucky that they’re not that terrible in comparison to AIDS for example, which is the champion of all viruses when it comes to amassing mutations and changes. AIDS accumulates mutations at a rate that is faster than the immune system, manages to evade immune responses, leading the body to constantly and chronically reinfect itself, without the ability to recover.”

Should the rate at which new Covid-19 mutations develop worry us? Could it make the race to develop vaccines a case of chasing after our own tails?

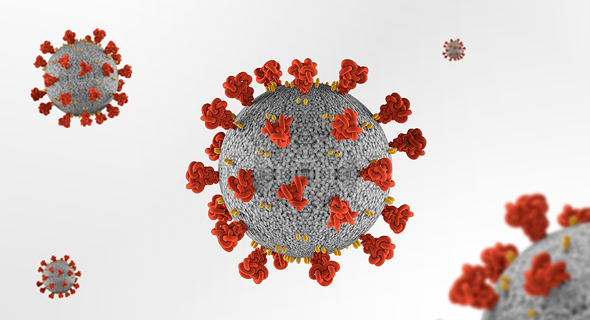

“The Covid-19 vaccines won’t become ineffective so quickly, because they cause the immune system to develop a multi-armed immune response: the vaccine doesn’t only work on one viral active site, but targets several locations on the spike - the protein layer that encapsulates the virus that resembles thorns and which the coronavirus has become associated with. The spike is a fairly large protein that has several sites that act as the virus’ Achilles heel: those sites bind to receptors on our body’s cells. The vaccines activate a successful immune response specifically against those sites, binds to the virus there, and blocks it from binding to our body’s cells.”

The coronavirus has many "spikes" which is a defining feature. Photo: Shutterstock

The coronavirus has many "spikes" which is a defining feature. Photo: Shutterstock

But those types of bad mutations can cause the vaccine to eventually lose its effectiveness.

“There is always room for concern that the virus’s vulnerability will change due to mutations, and the effectiveness of the body’s immune response will decrease. But, since the vaccine is effective against several locations on the spike protein, the chance that the mutation will render the vaccine ineffective is very low. The Pfizer vaccine is 95% effective; even if a mutation can cause that number to drop to 90%, it’s still a game-changer. Compare that to FDA requirements, which states that a vaccine’s efficacy threshold must be 50% or above. It’s possible that at some point the vaccine will lose its effectiveness, but this will only happen if the virus will undergo a radical change, and not a few single mutations.”

What do you think of the “British” and “South African” strains of the virus?

“It’s funny to call it that. I think that the same mutation randomly developed in other places in the world as well, independently, because it’s all a big numbers game. It’s true that the British were the first to identify the mutation, but that’s only because they have a good genome sequencing platform. When you uncover new information, you can discover terrifying new things. Perhaps a mutation like this was created also in Iran or in Israel, which has lately started to genetically sequence the virus?”

“There are places in the world where morbidity is rising in a way that seems more in line with the model of the British mutation than of the ‘old version.’ Wherever there is a higher rate of infection it may suggest that is the case. We must remember that searching for these particular mutations is biased because it ignores others. If we’re trying to look bright side, then we should be glad that so far there aren’t any indications of mutations that cause more severe symptoms, but only a higher infection rate.”

I mean, can this virus be any more aggressive?

“There is always the potential for it to be. This virus has a complete arsenal of proteins, aside from the spike, which operate inside the cell. There are also changes that can affect the severity of the disease and not just the potential for infection.”

If we must change the vaccines’ components, will we have to start over from scratch?

“Maybe in another two or three years, but it’s not a big deal, because we’ll simply readjust the new vaccines. In any case, it’s the regulatory aspect, not the scientific one that’s problematic: after all, only two days after the genetic sequence of the virus in Wuhan was released, Moderna already announced that it had a vaccine. It’s that simple: to sit with a file on the computer, program the sequence, press enter, synthesize it, and there you go, with a ready vaccine. It’s merely a couple of days’ work.”

“The hardest part is seeing whether or not it works and proving to regulatory authorities that it’s safe. That’s what takes time. I assume that once the regulatory authorities agree that it’s safe, approving a second version of the Covid-19 vaccine will be simpler and faster. It will be similar to the annual flu vaccine.”

Which vaccine is better? Is it the one with the higher efficiency rate?

“Whatever is available. For now, there is a global shortage of vaccines. Even with its high vaccination rates Israel won’t be able to forget about the coronavirus, because the entire world is in the same boat once the skies reopen for flights, and the large numbers of travelers could provide fertile ground for more mutations to develop. As long as world morbidity doesn’t decline, it won’t end - and even if you combine all the vaccines being produced today, I still don’t know whether they will be enough to vaccinate even a quarter of the world population. The Western world will have to consider how to vaccinate populations in weaker countries.”

Pfizer's Covid-19 vaccine. Photo: Getty Images

Pfizer's Covid-19 vaccine. Photo: Getty Images

The research team you’re leading is working toward finding an anti-Covid-19 drug.

“Yes, we are not trying to develop a vaccine, but a drug to cure people who’ve been infected. Currently, we’re at the animal-testing stage. The next step will be to convince a commercial body who wants to take this to the clinical trial stage, which is more difficult because it’s quite expensive.”

Is Israel’s enthusiasm for the vaccine a result of hysteria?

“That’s a question for psychologists, and isn’t my area of expertise. I can only guess that Israelis don’t like to be suckers, and that’s what motivates them and also creates this group dynamic of ‘everyone is rushing to get vaccinated,’ and now there is a competition for vaccination.”

“If we’re being serious for a second, it’s clear why 60 and 70-year-olds stormed the vaccination centers — the danger to their lives is tangible. After they led the charge without ramification, it spurred the rest of the population to get vaccinated. The real test will be young people since their risk to them is less tangible. Those in their 20s, it seems, failed to internalize the severity of the risk, some of them take part in parties. They shy away from the vaccine’s minimal risk or from the general unpleasantness of getting vaccinated. I’m curious about what will happen when vaccines become available to them as well, and how many will want to get vaccinated. It touches on social responsibility, just like two or three years ago when there were people who refused to get vaccinated against measles.”

How are you and your family coping while waiting for the vaccine to be distributed to everyone?

“My wife works in special education. They work all the time, during lockdowns as well, and that’s why I take care of my kids in the morning, and in the afternoon I go into the office. It’s a scenario that’s typical of Israeli families during these times. What bothers me is my wife’s risk of infection: some of the children in special-ed need close physical contact, need to have their diapers changed, etc. Every week or two it turns out that some child is sick, classrooms close down, and entire teams go into isolation. Those teachers need to receive the vaccine as soon as possible, just like health professionals are getting it, and rightly so. When that happens, my life will become easier.”