Can a Golem Have a Birthday and Other Questions of Legal Personhood

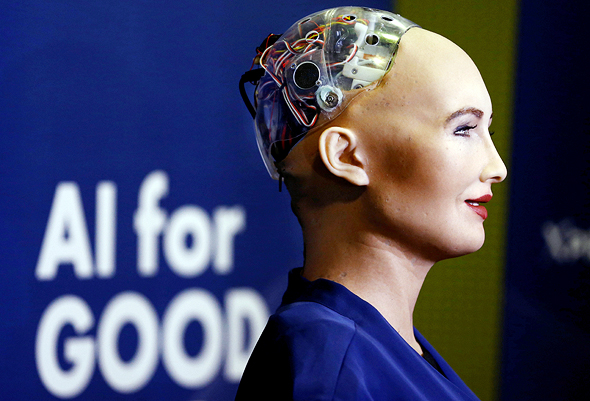

After ruling on the legal personhood of corporations and animals, courts must decide whether artificial intelligence should have legal accountability, as well as rights

This week, on the 20th day of the Jewish month of Adar, is the birthday of the famed Golem of Prague. Which begs the question—whether or not you accept the veracity of the underlying folklore—can a Golem have a birthday? More specifically, can a Golem have legal personhood such that its birthday is recognizable by the government? Or, more relevant for today, can an autonomous being, designed and made by a human, such as an artificial intelligence (AI) machine, have legal personhood with all of its associated rights and duties?

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

This is not a new question. There is a long history of non-humans obtaining legal personhood. From animals to corporations, jurisdictions have historically granted limited rights and duties to some types of non-humans, albeit mostly for economic efficiency. Most corporations, for example, are treated as sufficiently human-like in the eyes of the law as to allow them to enter into contracts, own property, or be liable for breaking both civil and criminal law.

While there have been extensive efforts to expand the scope of human-like rights to include animals, these often fail. In the U.S. court case Naruto et al v. David Slater, also known as “the monkey selfie copyright dispute,” People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) fought to have a macaque’s copyrights to a selfie he took acknowledged. Last spring, the appellate court ruled that animals cannot be granted the human rights associated with copyright.

In May of last year, the highest court in New York unanimously ruled that chimpanzees do not have the right to not be held captive or to be released to an out-of-state animal sanctuary. Unlike people, the court did not find that chimpanzees had a fundamental right to bodily liberty as per the nearly-universal right of habeas corpus.

While animal rights seemed to have stalled, some non-humans have seen their rights expand further in recent years, especially corporations. In 2014’s Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a corporation can have religious beliefs that it can act upon, for example, in refusing to provide contraceptives to their employees as part of their healthcare coverage.

In the 2010 case of Citizens United v. FEC, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that corporations have some First Amendment free speech rights, particularly in their right to finance public broadcasts of political messaging around the time of an election.

Pushing the scope of these rights even further, Amazon tried to claim free speech rights for its voice-enabled artificial intelligence service Alexa. In a 2017 case involving a murder that may have been overheard by Alexa, Amazon contended in court that “(Alexa’s) interactions may constitute expressive content that implicates privacy concerns and First Amendment Protections.”

While Amazon subsequently dropped that legal theory, with the ability of AI-enabled devices to collect, analyze, and present processed data, AIs are that much closer to assuming human-like rights and responsibilities, at least legally. But we are not there yet.

Around the same time that the U.S. courts were deciding the fate of animal copyrights, the European Commission decided against considering extending people-like rights and duties to AI. This was in contradistinction to the efforts of a committee within the European Parliament that sought to provide electronic personhood, mostly for facilitating the determination of responsibility when an autonomous machine causes a tort. That responsibility would likely be conveyed formulated via a requirement that all autonomous AI machines must have some liability insurance, just in case.

This failed effort might behave been especially helpful as AI algorithms become increasingly complicated and opaque, making it harder for manufacturers to appreciate and predict all the ways that their technology will interact with people and things. It will also make it harder to associate an AI’s moral failure to a corresponding responsible human.

While Electronic personhood would have made it harder to associate an AI’s moral failure to a corresponding responsible human, providing legal personhood to an AI would arguably help hold real people criminally liable for aiding an AI in the commission of a crime. If the AI could not be criminally responsible, it might be legally complicated to hold the AI’s human accomplices liable, but if an AI can be made liable for a crime, even if that AI cannot actually be punished for the crime, its human accomplices could.

Those against this proposed change in European law successfully argued that making AIs legally responsible for themselves would provide a disincentive for manufacturers to be ultimately responsible for their creations, perhaps even allowing the machines to run amuck without concern for the consequences. Providing even some aspects of legal-personhood to an AI could also force legal systems to reassess foundational legal principles such as mens rea—a person's intention to commit a crime.

The results of the European effort notwithstanding, granting person-like rights to an AI is a bit more complicated than what has been accomplished with companies. In contrast to corporations—which always have at least one actual human involved in their actions—AIs can be associated with physical devices that can directly interact with the environment without any human intervention. As such, AIs exist in an uncanny valley, where their proximity to humanity creates a visceral distrust that will need to be overcome as AI becomes more advanced, more prevalent and more human-like. In the end, the law will likely provide limited personhood to AI, albeit when it becomes convenient, legally expedient and transactionally necessary, like when a Golem wants to buy a cake for its birthday.

Dov Greenbaum, JD PhD, is the director of the Zvi Meitar Institute for Legal Implications of Emerging Technologies and Professor at the Harry Radzyner Law School, both at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya.