Stanley Fischer Got the Bank of Israel Addicted to Dollars, Says Former Bank Gov

David Klein, who served as the bank’s governor in 2000-2005, has plenty to say about the bank’s interference with the foreign currency exchange market, about its immense foreign currency reserves, and about the decision to keep the interest rate low

18:3601.12.19

Israel should reevaluate its economic policy, according to former Bank of Israel governor David Klein. In a recent interview with Calcalist, Klein was measured in his speech, but his experience and past positions mean his words are a resounding slap to the face. Klein headed Israel’s central bank in 2000-2005, a tomoulous time that started with the Al-Aqsa Intifada, continued with then-finance minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s severe cuts to Israel’s welfare system, and ended with the Israeli disengagement from Gaza. Unlike the superstar governors that preceded and succeeded him—Jacob Frenkel and Stanley Fischer—Klein was considered conservative and dull, not one to put a spoke in the wheel.

Today, at the age of 84, Klein still considers his words carefully but his message is sharp, even combative: the government deficit is too high, Israel’s foreign exchange reserve policy is out of control, the way numbers are rearranged to balance the budget is dangerous, and the premises according to which policy makers come to decisions are no longer relevant. For some reason, the changes that happened in recent years are not being taken into account when setting policies, Klein said.

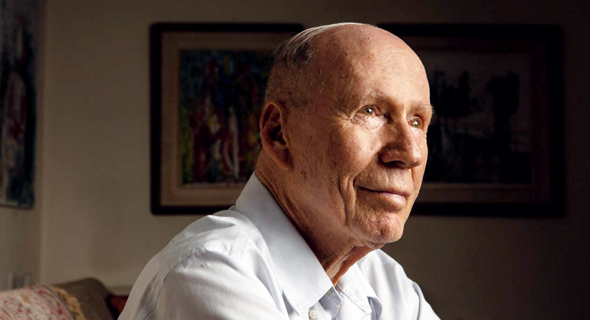

Former Bank of Israel governor David Klein. Photo: Alex Kolomoiskyצילום: אלכס קולומויסקי

Economists have always assumed that inflation increases the more unemployment drops, Klein said. This is because it was assumed that the more people earn, the more they buy, creating a demand that upps prices. In recent years that relationship was thrown out of balance—unemployment in Israel is low, but so is inflation, Klein said, and this change has not been reflected in Israel’s inflation targets.

The relationship between the interest rate and inflation also went wrong, Klein said. “The Bank of Israel thought the miniscule interest will increase inflation, and that didn’t happen either,” Klein said. “What did happen in the many years of miniscule inflation is that housing prices sky rocketed, long-term savings were harmed, and this is especially dangerous for the many investments made by pension funds and insurance companies that did not accumulate interest, meaning that those who reach retirement age will be very disappointed by their pensions.” The low interest rate also created immense liquid reserves, meaning huge sums of public money are laying around in people’s checking accounts or in deposits that yield no interest, he said.

The policy must change, according to Klein. Current inflation measurements do not take into account housing prices, which are on a continuous rise, for example, and that is why the inflation target is no longer relevant, he said. “When you tell the Bank of Israel, ‘you are responsible for stabilizing prices,” you must define exactly what prices it must stabilize.”

Another conception that must change is that low interest is desirable, Klein said. “Considering the negative effects of miniscule interest, this seems to be an outdated school of thought, and the interest should be higher—it should be upped gradually by 0.25% every time, until it is 2%. Under that level, interest only causes damage.”

Last week, current bank governor Amir Yaron decided to maintain Israel's benchmark interest rate at 0.25% and not cut it to 0.1%, surprising many who thought he would follow global trends. To counteract the shekel’s appreciation as a result, he announced a significant purchase of dollars.

Israel’s interest rate was raised for the first time in almost eight years in November 2018, under deputy governor Nadine Baudot-Trajtenberg, who served as temporary bank governor between Yaron and his predecessor Karnit Flug. “I thought she was starting a process, but then she was thrown out of the bank,” Klein said. “The fact is, nothing happened since she upped the interest rate to 0.25%. They should have kept going, but her successor balked.”

According to Klein, the governor acts based on recommendations from the bank’s research division, which may also be held captive by an outdated thought process. “Then they tell the governor, ‘look, Mario Draghi, the exiting president of the European Central Bank, has introduced negative interest rates, and you’re thinking of raising it?’ One of the things the current governor did is to say he is not thinking of upping the interest rate, choosing a phrasing as if to calm the markets,” Klein said. “I am not raising or lowering, I am waiting and in the meanwhile I am not making any decisions—that is what it means.”

Klein has some serious credentials. He has a doctorate in economics from The George Washington University and started his career at the Israeli Ministry of Finance. He held senior positions both in Israel and abroad, including at the International Monetary Fund. He joined the Bank of Israel in 1987, staying there for 17 years until he stepped down as governor. He then set on the board of Israel-based investment house Meitav Dash Investments Ltd. and insurance company AIG.

Interest and inflation aside, according to Klein, Israel’s biggest problem is the budget deficit. In October, the deficit was 3.7% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), compared to a target of 2.9%. Since the beginning of the year, the deficit increased by NIS 13 billion (approximately $374.5 million), compared to 2018. “The bigger the deficit, the more trouble the economy is in,” Klein said. “Credit rating companies do not like it, international investors flee from it, and Israelis do not like to invest in such a market, either. You cannot live with such a market for long.”

Israel’s Ministry of Finance and Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon were recently criticised for playing with the numbers, moving up tax collections and postponing payments to the next fiscal year to allow Kahlon to close 2018 under the deficit target. The budget should be managed appropriately all year round, not just at its end, Klein said. That means updating predictions throughout the year.

Though Klein has plenty to say about everyone and everything, it seems most of his criticism is reserved for Fischer, who succeeded him as governor in 2005 and became somewhat of a yardstick for those who follow. If Klein’s tenure was characterised by his non-interference in the foreign exchange market and his insistence that the free market should dictate the shekel’s exchange rate, Fischer did the opposite. He started what Klein refers to as the Bank of Israel’s “addiction” to buying foreign reserves.

Fischer’s move was unexpected, Klein said. It started as a reaction to a threat made by the Manufacturers Association of Israel and the Histadrut, Israel's largest trade union, that if Fischer refrained from taking action to stop the appreciation of the shekel they would move to advance a parliamentary committee that will determine the interest rate, Klein explained. “That bothered him a lot. He decided to increase the foreign currency reserves by $10 billion, and he was emphatic that it was not a policy. But then he got dragged into it, and eventually increased the reserves to $80 billion.”

The Bank of Israel started to buy foreign currency in 2008 and since then it has not stopped, Klein said. “It created a situation where the bank is seen as being committed to weaken the shekel. If the shekel appreciates they say ‘the Bank of Israel is not working, it needs to buy foreign currency.’ And though things have happened since within the Israeli economy that demand a policy change, the bank is deep in a nothing-happens mentality. There is inertia.”

At some point, Klein said, the bank understood that a reserve target is no longer a believable explanation, so it switched to a policy of responding to the market. “So today, we have reserves of $121 billion, and in relation to the GDP that is one of the highest ratios in the world. And not only does it not help, meaning it does not weaken the shekel, it creates a lot of negative side-effects.” One side-effect is that speculators who otherwise would have been more cautious choose to act because they can trust the bank will make a move if the shekel strengthens. Another is that those reserves cause huge losses to the bank—NIS 60 billion (approximately $17.2 billion) according to the most recent balance, Klein said.

Klein was also the last Bank of Israel governor to transfer the bank’s budget surplus to the finance ministry to cover the deficit. “If the Bank of Israel has a surplus, it should be given to the finance ministry.,” Klein said. “But Stanley (Fischer) found some way to integrate the reserves into the bank’s balance, like nothing is happening. He created the problem, and to explain he looked for excuses. I have no complaints about Karnit (Flug), who stepped into his shoes. She just did not dare to change the management style she inherited from him.”

Related articles

Klein is of the opinion that Israel’s fiscal policy should be the exact opposite of what it is today—that is, that Israel should sell its foreign currency reserves instead of increasing them. “It may be revolutionary, but we do not need to do it fast. We need to say that, regardless of the exchange rate, we are selling $25 million a day, gradually. It does not need to have much of an impact but it will accumulate. The policy needs to be target-oriented and the target is to diminish the foreign currency reserves and thus diminish the Bank of Israel’s deficit. Israel’s foreign currency reserves should not exceed $40 billion.”

The Fischer-esque policy that has dominated the Bank of Israel since his tenure should be corrected because it is not natural, Klein said. “There was a discussion in the literature about how one refers to a bank with negative equity, something that in a commercial company would be considered insolvency. Such a correction will decrease the bank’s negative equity, and maybe create some surplus for the bank to cover the government deficit, as the law dictates.”