Israel's Transportation Crisis Is a State of National Emergency, Says Former Transportation Ministry Director

Dan Harel, the former chairman of Israel Railways and former managing director of Israel’s Ministry of Transportation, spoke to Calcalist about the ills of the country’s public and private transportation systems

09:3324.02.20

Israel’s transportation crisis is nothing short of a state of national emergency, according to Dan Harel, the former chairman of Israel's national train company Israel Railways Ltd. Harel stepped down from his position earlier this month, after just two years. “If we do not declare a state of emergency, we will end up spending most of our time in traffic,” Harel said in a recent interview with Calcalist.

Harel, 65, joined Israel Railways following a 35-year career in the Israeli military, where he advanced to the role of deputy chief of staff. After retiring from the army in 2009 he was appointed managing director of Israel’s Ministry of Transportation, a position he left after just one year, due to disagreements with then-minister Yisrael Katz. “I wanted to set up a metropolitan transportation network but Katz refused for political reasons,” Harel said. He then held several public positions before joining Israel Railways.

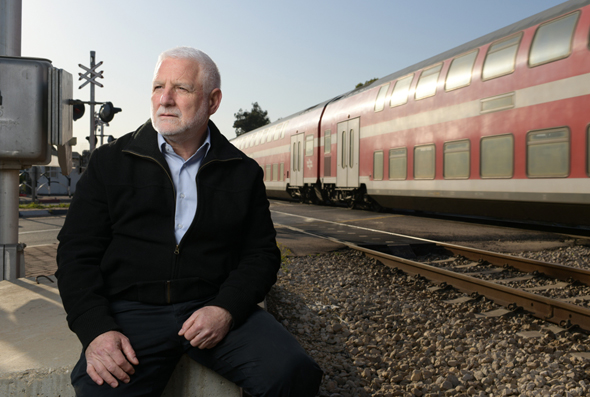

Dan Harel. Photo: Yonatan Bloomצילום: יונתן בלום

Harel said it was the severe crisis that caused him to join Israel Railways. As the quality of life in Israel rises, people tend to buy more cars and the government lacks the guts to tell them they cannot do that, he said. “In the 1990s they thought they could solve it by paving more roads and they put a lot of money into it,” he said. But, in this arms race, cars won big time. In 2015, Israel had between 215,000 and 220,000 new cars, and in 2017 and 2018, it saw 300,000 new cars each year, Harel said. Deducting old cars that had gone off the road, this still means 150,000 new cars, he said. “Say a car is 5 meters in length, these 150,000 new cars need 750 kilometers of road just for them to have somewhere to stand.”

In 2018, Israel paved 140 kilometers of new roads, but this was done outside of the metropolitan areas that are the most heavily congested, Harel said. The only way to solve this, according to Harel is to create public transportation lanes and have a functional railway system.

Harel places the blame for the train’s ills on the government, which he says refused to acquire well-needed train tracks and cars leading to over-crowdedness and delays. A double-deck car meant to house 144 passengers is at 190% capacity during rush hour, which means that people have difficulty coming on and off of it, Harel said. A delay of more than three minutes means the train missed its arrival window and this causes a chain reaction, he added.

“When I took the job we were approved 160 cars and a NIS 900 million (approximately $260 million) budget,” he said. But this was not enough. The train also needs more tracks, he said.

Related articles

Another issue Harel raises is that Israel uses intercity trains that weigh 300 tonnes as if they were light rails. Intercity trains take a long time to stop and using them only makes sense for long distances where the train can reach high speeds, he said. In the Tel Aviv area, for example, such a train makes six stops, and none of these stops has sufficient supplemental public transportation, he added.

Harel believes the solution is at least two new tracks connecting Tel Aviv and Haifa and four more tracks on Israel's Highway 20, also known as Ayalon Highway. He also warns against an existing plan to dig underground rail tunnels between Ben Gurion International Airport and Tel Aviv suburb Herzliya. “It is going to start at NIS 30 billion (approximately $8.6 billion) and end with NIS 70 billion (approximately $20 billion),” he said. They should just build a bridge over the highway as they do in Europe, he added.