Shells, fuzes and a 2,650% return: Inside Aryt’s explosive growth

How a reclusive owner, a late-career CEO, and relentless demand turned an overlooked factory into a stock market phenomenon.

You don’t have to be an expert on the capital market or follow what’s happening on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE) every day to know that since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine - and even more so since the Gaza war began in October 2023 - shares of companies in the defense sector, now commonly called defense-tech, have generated extraordinary returns on the TASE. But even compared to well-known companies like Elbit Systems and Beit Shemesh Engines, which have enjoyed surges in revenue, profitability, and share prices, the modest Aryt Industries stands out.

The share price of the Sderot-based shell fuze manufacturer has risen by about 140% since the beginning of this year and by about 350% in the past 12 months, almost nine times the return of the Tel Aviv-125 index over the same period. In the past three years, since the Ukraine war broke out and ignited a global arms race, Aryt has delivered investors a staggering return of 2,650% (27 times their money!). Naturally, the IDF’s enormous demand for fuzes for tank, cannon, and mortar shells is directly responsible for this surge. In 2024, Aryt reported sales of NIS 126 million (approximately $37M) and a net profit of NIS 60 million ($17.7M), and looking ahead, it has a backlog of orders worth more than NIS 1 billion ($290M) for the coming years.

This success has also surprised those at the top of the company. The controlling owner (51%) is the ultra-Orthodox businessman Zvi (Zvika) Levi, who avoids any publicity, does not give interviews, and refuses to be photographed. He acquired control in 2006 for about NIS 14 million ($4.13M), while today Aryt is worth about NIS 2.1 billion ($620M). Alongside him, the CEO for the past three years has been Haim Stapler, 71, who took the role at the age of 68 - after he had already retired.

The meeting with Stapler takes place at Aryt Industries’ sterile headquarters in Or Yehuda, where only the models of shells and fuzes scattered around hint at the company’s deadly mission. “Our nickname used to be ‘the little company from Sderot,’ and it’s hard for people to change how they think about us, but I haven’t heard that phrase in a year,” Stapler tells me proudly at the start of our conversation. “On the stock exchange, we’re in the ‘century club’ - companies whose value has grown by over 100% every year for more than two consecutive years. There aren’t many companies like that, and it makes us proud. If it happens for a third year, that would be crazy.”

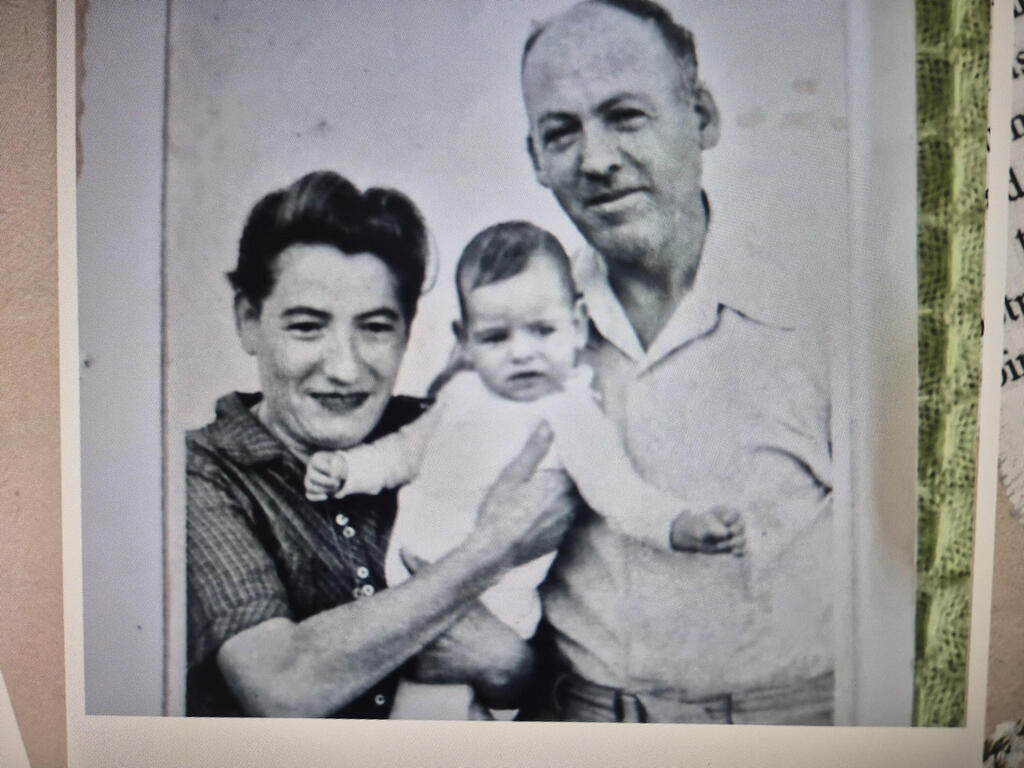

Stapler is far from the typical CEO of a defense company. He didn’t come up through the army ranks, he didn’t emerge from high-tech, and he had no network in the defense establishment. What he did have was management and executive experience, a rare personal charm for the arms industry, and a kind of emotional detachment learned at home, all of which turned out to be significant advantages in the role he took on. “I grew up in a one-and-a-half-room apartment in Tel Aviv’s old north with my parents, who were Holocaust survivors,” he says. “We barely got by on my father’s income as a shoemaker and compensation money from Germany. My mother didn’t work, she served my father and fed him boiled chicken every day. Her role in life was to make sure I survived. After giving birth to me, she struggling so much mentally that she placed me in a boarding school for three years, while she received treatment. To this day, I have a photo of myself being held by the caregiver who wanted to adopt me.”

What was your relationship with your father like?

“It was difficult. He came out of the Holocaust with feelings of guilt for surviving when his family did not. He was completely emotionally detached, and I learned from him how to separate daily life from the soul. I have thick skin and I don’t take anything to heart. Maybe that’s also a remnant of the boarding school where I grew up. I learned not to feel there.”

Stapler enlisted in the Artillery Corps in 1971 and started his career wiring electrical panels. After studying electrical engineering, he began designing panels at Katzenstein Adler, where he first met Zvi Levi. Later, the company he worked for was sold to Elco, and Stapler moved to the German company Siemens, eventually rising to VP of sales and marketing for Israel. “I sold power plants, trains, printing presses, and industrial projects worth 100–150 million euros a year,” he recalls.

How did your parents feel about you working for a German company?

“It was difficult for them, but they never said a word. To their credit, they knew how to be supportive.” In 2008, after Levi invested in Aryt, he approached Stapler and offered him a position as an external director while he was still at Siemens. After nine years, the maximum term for that position, they temporarily parted ways. “Aryt was a small company then, worth about NIS 40 million, and Zvi told me to call him when I retired from Siemens,” Stapler says. “When I did retire, I called him and he suggested I join Aryt as co-CEO. Since I’m a hyperactive person, I agreed. I knew the company, the customers, and the field well from my artillery service, so for me, it was like closing a circle. At first, I worked part-time, about 20%, but that gradually increased, and today I’m the sole CEO. Officially I’m supposed to work 80%, but in reality, I work at 300%.”

Few people begin their CEO careers at 68.

“My nature is to want to conquer the next goal. Some people retire and say, ‘Now I’m going to travel abroad,’ but that doesn’t interest me. At Siemens, I traveled abroad so many times that I can hardly stand to see another airport. On the other hand, someone who has worked for an international company and was constantly on the move finds it hard when they’re suddenly told to stop. And maybe it’s just my crazy head, but for me, when someone retires, they start counting down the days.”

“A boutique detonator company”

Stapler holds a shell detonator in front of me. “A detonator is the part that connects to the shell to activate the explosive material inside it. There are time fuzes that activate after a set period, impact fuzes that detonate when the shell hits a surface, and proximity fuzes that explode when the shell nears its target. What’s unique about our detonators is that they’re electromechanical. In relatively simple and inexpensive mechanical fuzes, the firing mechanism relies on rotating gears - Hamas, for example, manufactures such mechanisms. In our detonators, the firing system is electronic and therefore much more reliable. This is essentially what makes us a boutique detonator company. You can count companies like ours on one hand.”

Stapler’s “boutique” has been expanding rapidly. In 2022, Aryt’s sales to the Ministry of Defense and Israeli defense companies totaled about 18 million shekels. Two years later, they jumped more than fourfold to 80 million. Today, sales to Israel’s defense establishment make up 64% of the company’s operations, while Aryt also sells detonators to India and recently won a tender to supply a customer in North America.

“Since 2022, the company’s value has increased twentyfold, and there are investors who have made millions from investing in us,” Stapler says. “When we open subsidiaries in the United States or Europe and set up production lines there - as we’ve done in India - and when we launch our new product (solar roofs for generating electricity for agriculture and other uses), people will already look at us differently.”

The vast majority of Aryt’s detonators are manufactured at its subsidiary, Reshef Technologies, which operates in Sderot. “Our rapid growth happened even though Reshef’s factory in Sderot came under heavy fire after October 7, and all the residents of Sderot, including our employees, were evacuated to Eilat and other parts of the country,” Stapler explains. “The factory itself was also hit, and we shut down for a month or two. But we had commitments to India for continuous supply, so we couldn’t just say, ‘Sorry, that’s not happening.’ At the same time, the IDF began pouring in orders, and we also signed a deal with a North American company to supply detonators worth 300–400 million shekels this year. So we reopened the factory as soon as we could.”

How do you manage to deliver all that without employees?

“The organization was incredibly challenging. We had nothing, and we still had to deliver. Taking on all these orders was a gamble, so we had to switch into emergency mode.”

What did that mean in practice?

“In a war, when people receive compensation from the state, why would anyone come to work, right? So I told the employees they needed to come back immediately, and that if I brought in replacements, they wouldn’t be able to return to the company later. The veteran workers came back, some didn’t, but we grew from 40 employees to 250. At the same time, we expanded the factory’s production areas to six times their original size. We rented every available space in the area, expanded the warehouse, and created separate production lines for each product. Our entire outlook changed during the war. Instead of producing tens of thousands of fuzes a year, we had to produce 400,000–500,000. We even set up classrooms inside the factory because the most critical skill for making fuzes is soldering electronic boards. It’s a very specialized skill, you need dexterity and precise technique. So we opened a training school to teach new workers. Right now, we have 30 students every month. Mothers from Sderot, Be’er Sheva, and Arad work for us.”

“Shall we sit back and let them kill us?”

The fuze market is estimated at about $1 billion a year, and according to analyst reports, it is projected to grow to $1.7 billion by 2031. However, contrary to what one might assume, not every rise in regional violence benefits Israeli companies. In a conversation with Stapler, a day after Israel launched a war against Iran, he emphasizes that the new front could actually hurt business.

“This is an air force war - it doesn’t affect us,” he explains. “Our products are related to three artillery areas: mortar shells, tank shells, and drone armament, for which we’re currently developing fuzes. But the war makes things harder because the skies are closed. When there are no planes and no transport, it’s hard to export. We also have to remember that our market is a ‘projectile’ market, so I need to diversify with more business lines. That’s why I need subsidiaries, so if one line performs poorly one year, the other can compensate.

“This is a good opportunity to explore acquisitions in both defense and civilian sectors. Right now, for example, I’m looking at a drone company with civilian market applications.”

A “projectile” company lives from escalation to escalation.

“And what if there are no wars at all, so there’s no need for detonators? Detonators are always needed. Armies train constantly, so there’s ongoing demand. And if we gain a foothold in a foreign military like India’s, the potential is endless. India’s borders are so vast they can’t fence everything, so they shoot to mark their territory, which means they need detonators. From 2015 to 2025, we supplied them with a million detonators, and for every shell they sell, I supply 37% of the detonators. In 2024, we signed a contract for another five million detonators over ten years. India isn’t at war - and look at how much they consume.”

From a business perspective, it’s good for your company if the war in Gaza drags on endlessly.

“I wouldn’t say I want the war to continue forever just to keep getting orders. That’s not how it works. Businesses prefer stability, a flood of orders can stress the system. For a company, living with wild fluctuations is terrible. One day they tell you, ‘Here’s a million dollars, just keep stock for me,’ and the next day demand collapses. That’s why, during peaceful times, we’ve been developing a green energy system under our subsidiary Aryt Sustainability. It’s a dual-use solar installation we’ll launch in a year. For the next 5–10 years, they’ll need everything, both our fuzes and our solar roofs.”

Still, Aryt is a “war stock.”

“To say ‘they profit from war’ is simplistic. Does Elbit, for example, only profit when there’s a war? No, it benefits from global tensions. Since the Russia–Ukraine war, all of Europe has started to think differently. They’re building shell factories like crazy. Countries like Denmark and Finland, which you’d expect to focus only on peaceful civilian industries, are now investing heavily in armaments. They’ve realized that today, being unprepared for an attack is a crime. It’s in human DNA, wars will continue to happen, and the point is to be ready. So countries prepare even if no war breaks out. that’s a long-term story. You can’t close capability gaps overnight.

“The Ukraine war didn’t help me directly, because our Defense Ministry doesn’t approve sales to countries in conflict, neither Russia nor Ukraine. But indirectly, we benefit from Europe’s rearmament. We recently signed an MOU with a Danish company for knowledge transfer, essentially a distribution agreement for Europe. At the end of 2024, we closed a deal with Bharat Electronics, India’s equivalent of Elbit, for another ten years, guaranteeing about $20 million in annual revenue. Last year, we signed a single order with a North American customer worth $320 million, to be delivered in 2025, with hopes for future continuity. The idea is to ‘put a foot on the ground.’ If you want to sell in the US or Denmark, you need a local presence. You can’t just sell them parts from afar, you have to enter an existing factory, set up a line, or build a new factory at the customer’s site. Every country insists that production happens on its own soil.”

You speak from a cold business perspective. Do you have any issue with the fact that the shells your fuzes trigger can kill innocent people?

“Of course I do. But it happens by accident, not out of malice. In war, you can’t fully control collateral damage, and the better and more reliable the fuze, the less chance of harming civilians. For me, collateral damage also means a faulty fuze that fails to detonate, then you’ve basically handed your enemy a free missile for their own stockpile.”

And you’re completely at peace with being a significant player in the arms industry?

“Saying the arms industry isn’t legitimate is like saying, ‘Let’s sit back and let them kill us.’ I’m the child of Holocaust survivors - Jews who had no way to defend themselves. So this is an industry that saves lives too. Without it, we wouldn’t survive here. If we invested 100% of our money in education alone, would you feel safe enough at the borders?

“By the way, sustainability is our way to balance our main business: fuzes kill, but our solar systems help save humanity. I hope one day our green product sales will surpass Reshef’s sales. The green market is huge.”

“The entire vision is Zvika’s.”

This business creativity, says Stapler, “is all Zvika’s vision, the owner’s vision, who understood exactly what armies would be looking for.”

A vision of war?

“He saw Aryt as a company producing a product that others don’t have and realized there would be a market for the best in the world.”

What is his background?

“He’s a proud native of Tiberias, from an ultra-Orthodox family, and a businessman par excellence. Some people take courses and earn degrees all over the world, but Zvika wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth, and look where he ended up. He’s a great marketer, and you can tell that within seconds.”

Why did an ultra-Orthodox man from Tiberias invest in a defense company?

“He invested in Aryt because he was looking for a listed company. But unlike other investors who came and went, buying shares to make a quick profit and then selling, Zvika believed in Aryt and didn’t walk away even in the tough years. He’s someone with real passion for what he does, and he’s a very serious trader. He’s an owner who’s personally involved in every detail - that’s his strength and the secret to his success. He’s not one of those ‘launch it and forget about it’ businessmen. And the vision he had really worked.”

How did the connection between you two come about?

“He founded Ral Electric in Tiberias, which was a family company that manufactured electrical panels, and I was managing a subsidiary of Katzenstein Adler that sold him equipment - so we grew up together professionally. We had an excellent working relationship and stayed in touch for 20 years. In the end, he suggested that I join Aryt as an external director. He wanted to strengthen Aryt’s marketing, and he mostly works with people he’s known for years. That’s very important to him. He and I share the same passion for marketing, and we understand each other.”

Why isn’t he well-known? You can’t even find a picture of him online.

“He’s a man of faith, and he believes publicity does no good - so he prefers to stay out of the spotlight.”

You’re both unusual figures in the defense industry, you can tell by your candid language.

“Military people are usually less outspoken when it comes to building connections,” he smiles. “Zvika and I aren’t ex-military; we’re marketing people. In our industry, you can’t be inhibited, it just doesn’t work. You have to know how to connect with your customer.”

Does the arms embargo on Israel, which is starting to take effect, affect you?

“Absolutely. Some sub-suppliers have stopped supplying us, so we were forced to develop certain product components ourselves, and we did. There are countries I won’t name that always used to work with us without a problem, but today they won’t supply us. I’m not talking about Europe, but about other countries that, in times of conflict, simply decide they don’t want to deliver. In those cases you can try to persuade the supplier, but it’s not up to them, it’s up to their government. That’s why local Israeli production is so important, so we can minimize our dependence on foreign suppliers as much as possible.”

England, Spain, and other countries are already openly boycotting.

“We don’t work with England, so its embargo doesn’t affect us directly. And we’ve found workarounds to source missing components or raw materials by partnering with other countries. But it’s not easy, you’re still dependent on other countries. Some refuse to supply, others might suddenly hike their prices drastically. That’s why we need production independence. You can’t just rely on American stockpiles - when one war ends, you have to be ready for the next one.”