“I don’t want to be the richest man in the cemetery” — Morris Kahn on giving it all away at 95

The tech billionaire who co-founded Amdocs is spending his final chapter investing in life-saving science and telling old regrets to get lost.

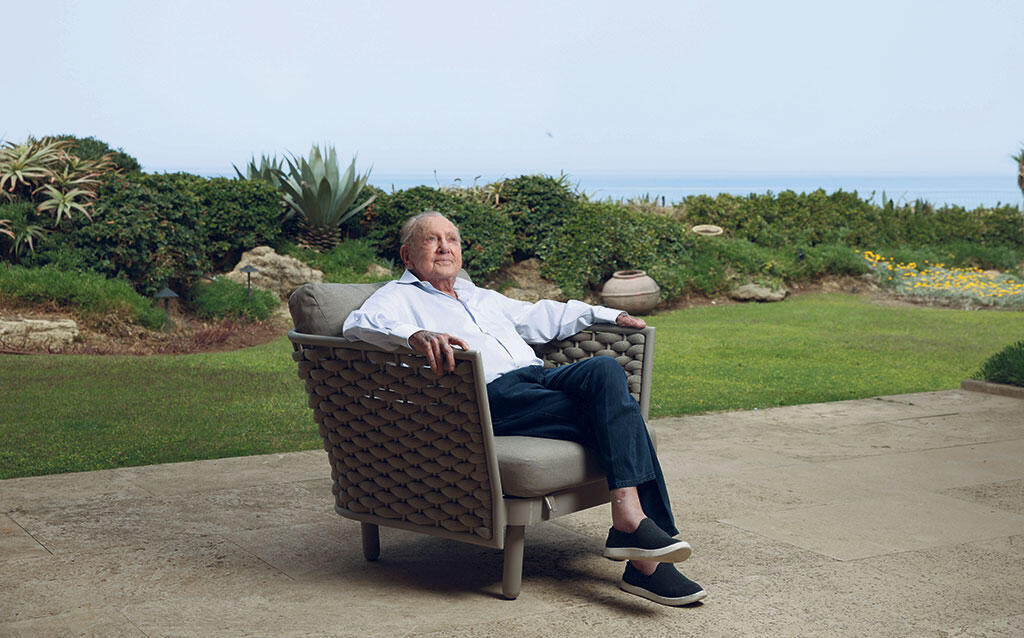

Morris Kahn’s bedroom in his villa in Beit Yanai offers a vivid reflection of the 95-year-old billionaire’s life: massive glass walls overlook the sea, creating the illusion that the room is in the water. Above the bed hangs a large painting of a nude woman reclining on her side. Beside the bed stands an oxygen tank.

“My body is betraying me, in a way,” he says, speaking through a device connected to his hearing aid. “But I can still go on with what I have. The secret is love. It’s an important spice in life. I like to be around people who excite me. I can even show you pictures of my girlfriends,” he laughs. “I’m lucky I’ve always been able to do what I wanted to do. A beach in Thailand is nothing compared to what I have here in my bedroom.”

Your aunt passed away in South Africa two years ago at the age of 112. Is that a good prognosis for you?

“She’s not the only one. My great-grandmother lived to be 100 back in the old days, before modern medical treatments. We have good genes. But I don’t want to live to 112. I’m grateful for every year that I have something meaningful to do. I don’t want to end up as just a sick old man being taken care of.”

Are you frustrated that old age can’t be cured?

“Try talking to my friend Sami Sagol. He wants to live forever and will brainwash you about it. That’s why he set up a pressure chamber at Assaf Harofeh, and I set up another one with him at Ichilov. Have I tried it? No. I’m not allowed to, given my condition.”

Did you tell him, ‘Sami, between us—does it really work?’

“No. Why would I spoil it for him? He never wants to die. I’m the opposite. I don’t want to add years to my life—I want to add life to my years. And there’s a price for that. I do things that make me happy, even if they might shorten my life.”

Like what?

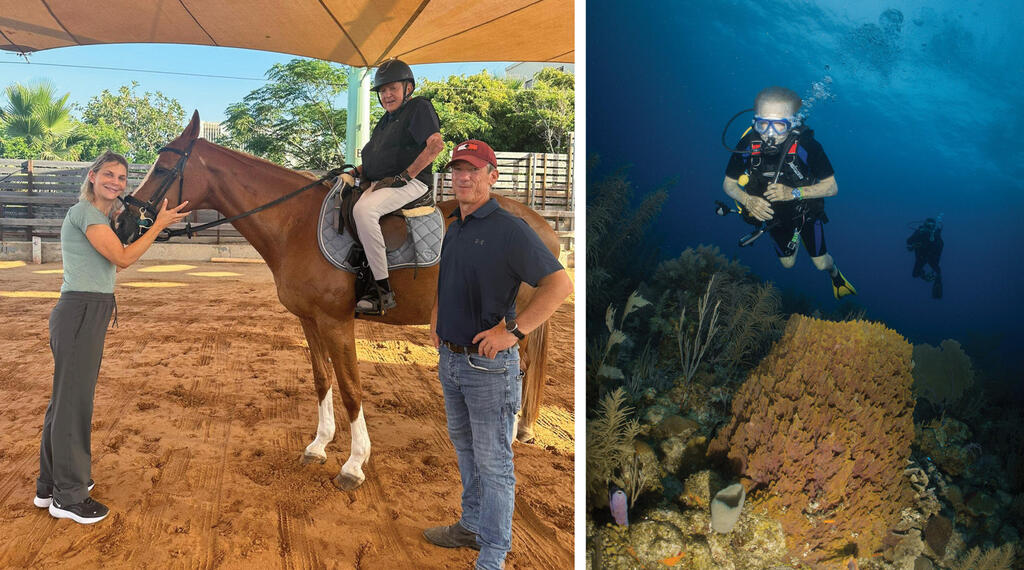

“If I told you, they’d send me straight to jail,” he laughs. “But, for example, they banned me from diving because my lungs could explode. I suffer from pulmonary hypertension, and my heart is a junkyard—I’ve had more than ten procedures and surgeries. Two months ago, doctors explained in detail all the ways diving could kill me. I said, ‘Okay. But this is what I want to do, and this is what I’m going to do.’ So I did. In the past, I used to dive twice a year with friends—scientists, NASA people... something special. Like Buzz Aldrin, for example. He and I are the same age, and like me, he’s not especially responsible either.”

You smoked until recently.

“I wasn’t a heavy smoker. I quit more than two years ago. And I did more than just smoke cigarettes.”

Weed?

“No. I tried it and didn’t like it. But if you want a recommendation, you can get it privately.”

So how do you add life to your years?

“I have a young girlfriend. She’s a bombshell. You can see a picture—I’m not ashamed. What did I do wrong? My wife passed away 20 years ago, and I’m not a monk.”

Have you done anything you regret?

“I remember the pleasures to the end. I forget the regrets. I came from a very poor family. But today, I have a Mercedes, a Porsche, and a Jaguar in the garage. I have a yacht in the marina. I have a plane at the airport. And right outside this house, I have horses. My riding instructor and I are working on a way for me to ride with a small oxygen tank, because the regular one is too heavy for a horse. So yes, I live like a lord or a prince—but I earned it honestly, and I also help people.”

How do you get to 95 in this condition?

“One of the secrets is to stay active and live a meaningful life. I wake up every morning with coffee and four newspapers, I meet people and take care of things. I admit I’m starting to get tired—at 95, I don’t have the same strength or drive I used to have. But as long as I don’t lose my intelo, I don’t have a problem. Because that’s who I am.”

2 View gallery

Kahn dives in Eilat and at his private stable in Beit Yanai.

(Photos: Adam's Undersea Adventures - Adam Baxter, courtesy of the family)

Yellow Pages and Amdocs for Philanthropy

Morris Kahn is one of the first billionaires to emerge from Israel’s high-tech sector. He founded Yellow Pages in the late 1960s and later co-founded software giant Amdocs. In the 1970s, he also established Coral World, the company behind the underwater observatory in Eilat. Run today by his son, Benji Kahn, Coral World has since built underwater centers in Australia, Hawaii, Spain, and other locations.

Today, Kahn devotes most of his time to philanthropy, into which he has invested roughly $200 million to date. He founded LEAD, an organization dedicated to developing young leadership in Israel, and supports nonprofits such as Zalul (founded by his son Benji) for environmental protection, the Movement for Quality Government, and Save a Child’s Heart, which brings children from developing countries to Israel for life-saving heart surgeries. He is also a major backer of biomedical research, having invested $50 million in the field.

“Two days ago, I attended the opening of a manufacturing lab for Precise Bio, a company that prints corneas—and soon, retinas,” he says. “I invested several million shekels in it. In two months, they’ll implant the first cornea in a human as part of a clinical trial. The global demand is huge. Right now, a patient needs to wait for someone to die in an accident or murder to receive a cornea. For every cornea available, there are seven candidates.”

What was your last investment?

“I’m currently considering a nanomolecule that could potentially cure cancers of the digestive system. I’m looking at it carefully before diving in. This is a world that moves slowly, and I’m already 95. I tell people, ‘Shoot me if I make another investment,’ because at this age I should just focus on what I’m already involved in. I swore to myself I was done—but I’m probably addicted to the satisfaction of being part of something that can change lives. It gives me a sense of meaning.”

Is it more important for you to be remembered as a biomed investor or the founder of Amdocs?

“Amdocs is the past. It gave me satisfaction and financial security, which now allows me to do what I really care about. What could be more important than saving a life? That’s the only thing that gives real fulfillment. Otherwise, what is life? You’re born, live, and die. I don’t want to be the richest man in the cemetery. In fact, I’m no longer a billionaire—I’m a millionaire. Where did the money go? Philanthropy. I plan to leave my children a reasonable amount, not everything. The rest will go to philanthropy.”

Kahn’s most publicized investment was in the Genesis project, in which the SpaceIL nonprofit launched the first Israeli spacecraft to the moon in 2019. The mission ended in failure when the probe crash-landed due to human error.

Do you regret spending tens of millions on a probe that crashed?

“I’m proud of it. We were the first non-governmental organization to reach the moon, and we did it with relatively few resources. It was an incredible achievement—we got there in a very innovative way: hitching a ride on a rocket that orbited Earth.”

But it crashed.

“I call it a ‘hard landing.’ The main thing is that we reached the moon. It also had enormous educational value. Kids dressed up as astronauts that year on Purim.”

In 2021, Kahn launched the Beresheet 2 mission and raised $45 million for it—but in 2023, he abruptly pulled the plug.

Why did you abandon the dream?

“Because once in a lifetime is enough. It’s a luxury to pursue a project like this now, when the country has other, more urgent needs.”

“It’s Not a Tragedy to Fail”

Kahn grew up in South Africa but struggled with the realities of apartheid. “I was expelled from university in Johannesburg because I was a communist,” he says. “All my friends went to prison, so I ran away to a remote town and opened a shop—my first failure. I went back to my mother and said, ‘I’m not cut out for business. What am I going to do about all the people I owe?’ And she said, ‘Thank God this happened to you at 20 and not at 60, because you would’ve been finished. You’re young. Start again.’”

At 25, Kahn immigrated to Israel and bought a farm in Beit Yanai. A year later, his wife Jackie and their two children, David and Benji, joined him. But his business journey in Israel was also filled with early setbacks—from a bicycle factory at Kibbutz Tzora to a cattle breeding venture in the Hula Valley, and a leather glove factory.

“Young people today are afraid of failure,” says Kahn. “But my message is: failure is not a disaster. I succeeded only because I didn’t give up. Every time I fell, I got up again.”

His breakthrough came in 1967, when he won a Ministry of Communications tender to market telephone directories with his company, Dapei Zahav. In 1982, he partnered with Avi Naor and Boaz Dotan to establish Orek Information, which computerized telephone directories and operated internationally via a U.S. entity called Amdocs. Amdocs later evolved into a provider of billing and customer service software for telecom companies.

Success came quickly: within three years, 50% of the Orek Group was sold to Southwestern Bell. In 1998, Amdocs went public in the U.S. at a $2.75 billion valuation. Kahn sold shares worth about $1 billion. In 2004, he sold his Yellow Pages stake to the Markstone fund for another half-billion shekels.

“Morris is a marketing wizard,” says Naor. “He can charm anyone—even top executives. When he walks into a room, he owns it. Much of Amdocs’ success is thanks to his charisma.” Others note the more combative side of Kahn’s personality: “He’s not easy,” says an acquaintance. “He loves a good fight and will battle ferociously for what he sees as his—even greedily.”

On Trump and Israel

As someone who owes his fortune to the U.S. market, what do you make of Donald Trump’s isolationist tariff policies?

“I don’t understand what he’s trying to do. He’s driving the world crazy and wrecking relationships the U.S. has built over decades. Yes, the U.S. has given more than it’s received—but Trump acts like a bully. He’s causing long-term damage. His tariff policy will make the world more miserable. I believe in cooperation, not confrontation.”

On Israel, Hamas, and the hostages—Trump seems to be on your side.

“We’re lucky Trump feels that way. It’s a big surprise. He really does care about Israel. He’s charismatic, motivated, and speaks directly to the American people. That’s what made him the most powerful man in the world—the regional sheriff, maybe even a king. The hostages thank him, because he was the one who threatened Hamas. I believe Bibi cares about the hostages too, but he’s a politician, and he’s trying to survive—so he’s navigating both worlds. But there’s no doubt: we haven’t done enough to bring the rest of the hostages home. That’s why we need Trump’s help.”

“We got a wake-up call”

As a long-time philanthropist and supporter of the Movement for Quality Government, Morris Kahn has strong views about Israel's current political situation. "I'm deeply concerned about the ongoing attacks on the judicial system," he says. "It troubles me that politicians are making decisions instead of professionals, and I feel that the public isn’t being adequately protected. An independent judiciary is the heart of the country, and it must not be compromised. I support reforms, but the changes this government is promoting are undermining the foundations of our democracy.

"And when the commander of the Navy is disqualified from heading the Shin Bet just because he took part in a protest—it’s disgraceful. But this is the country we’re living in under the current ruling party."

He then adds, nodding, "By the way, I once dated Ariela, the mother of Education Minister Yoav Kisch."

What’s the issue with Ariela being Kisch’s mother?

“There’s no issue. Ariela is a lovely woman, and I enjoyed our relationship. But I don’t appreciate what her son is doing—diverting money from general education to Haredi schools. He’s one of those Likud politicians who’s trying to please Bibi Netanyahu, and I don’t respect that.”

Is she still your partner?

“No. Life moves on.”

What worries you most about Israel today?

“Our international standing. Antisemitism has always existed under the surface, but now it’s out in the open and has become socially acceptable. That worries me. You can’t wage war on Hamas in a polite, civilized way—and that’s fueling antisemitism, especially among people who don’t even know where Israel is on the map. But we are, generally, ethical people. The destruction you see on TV is terrible. Innocents are dying. But we didn’t start this war—it was forced on us, and we’re fighting to survive.”

In an interview with Calcalist 12 years ago, Kahn said: “The Palestinians have a right to their own state, and we need to divide the land between us. The injustice infuriates me.”

Today, you sound different.

“I know. October 7 was a terrible wake-up call for Israel. Can we live with the Palestinians? It will be very difficult. We failed miserably by being caught unprepared. We let ourselves be lulled to sleep by the Qatari money flowing into Gaza, and only later did we realize that they were far more sophisticated than we thought. We’re guilty of letting this happen. We were shocked by how much they hate us and want us gone. Now we want to destroy them. That’s the reality.

“I don’t believe there’s a viable solution to the conflict at this moment. We must believe that one day a solution is possible—but it will take hard work and time. If someone wants to dream of a Palestinian state, let them dream, but they should be careful when they wake up.”

As a former immigrant, how do you feel about Israelis leaving the country?

“It’s natural for people to want to protect their children. Everyone has the right to choose how and where they live when faced with uncertainty. My children and grandchildren are still here—but like many Israelis, they’ve taken out foreign passports. Mentally, Jews are used to living out of suitcases.”

“Being like me is not such a compliment”

One of the more surprising aspects of Kahn’s story is that, unlike many billionaires, neither of his sons has followed in his business footsteps.

“David is a psychologist. He treats patients and invests his money wisely, but he doesn’t care about getting richer,” Kahn says. “Money doesn’t motivate him, and I respect that. I’m not disappointed that he didn’t go into business. Benji, on the other hand, is more of a builder. Right now, he’s constructing a spectacular aquarium on a river in the heart of Berlin. I’m proud of them both.”

You said they were angry with you. Why?

“I worked a lot outside the home, and they felt my absence. Back then, I didn’t realize it was a problem—but even now, when they’re adults (David is already a grandfather), I still hear complaints.

“I feel I gave them values, opportunities, and a good life. Benji turned out to be a bit like me, but David is more like his mother. When he earned his psychology professorship, I saw just how much value there is in him. He’s very humble, and what he cares about is his patients—and that’s a good thing. Being like me isn’t necessarily a compliment.”

That’s a typical struggle for sons of strong fathers—you can never quite live up.

“My father immigrated alone from Lithuania at age 12, with no parents, no language, no education. He never succeeded, and I don’t remember ever having a meaningful conversation with him. Only when he was sick and near death were we finally able to talk. I saw that as a loss. I wanted a father who would guide and inspire me. I didn’t have that.

“Later, I realized that my children also had a strong and difficult father—and they suffered for it. But maybe the lack of a strong father in my own life made me who I am. I had to do everything by myself. There’s always a kind of balance.”

You were asked onstage at your birthday what you miss, and you said: your wife. That’s a bit surprising, given your image over the years as a man of many women.

“Jackie died 20 years ago at age 75. She understood me, supported me, and let me do what I needed to do. She was an important part of my life. I love women, and she never minded that. She loved me, and I loved her. We had trust, even though I wasn’t an easy man to trust.

“She was a very good person who gave a lot to others. She had heart problems, and she told me she’d die at 75. On her 75th birthday, we managed to go out to dinner in Caesarea. We brought her there in a chair. She didn’t have much strength left. Five days later, she passed away.”

You talk about your tough character, but you’re also known as a hedonist who loves the good life.

“I do enjoy life—cruises, new experiences—but those are fleeting pleasures. When you do something for others, the satisfaction is immense. That’s why I do philanthropy. Not to have my name on a building—it means nothing to me. People put their names on things because they want a sense of permanence. I’ve never wanted that. In fact, I recoil from it.”

So—see you in five years for another interview?

“I hope so.”