The battle over end-to-end encryption: Legislation threatens user privacy

A new law proposed in Britain, aimed at protecting children's safety, could set a dangerous global precedent for accessing encrypted messages, jeopardizing the privacy of journalists, human rights activists, diplomats, and all users

On July 20, a Nebraska court is expected to sentence Jessica Burgess, a 42-year-old woman who provided her 17-year-old daughter with pills for a late-term abortion, resulting in a two-year prison term. This case garnered attention as it raised concerns about prosecutors targeting individuals seeking abortions and those supporting them. It also underscores the privacy issues surrounding Meta's compliance with a search warrant, leading to the handover of private chats between the mother and daughter on Facebook to law enforcement authorities.

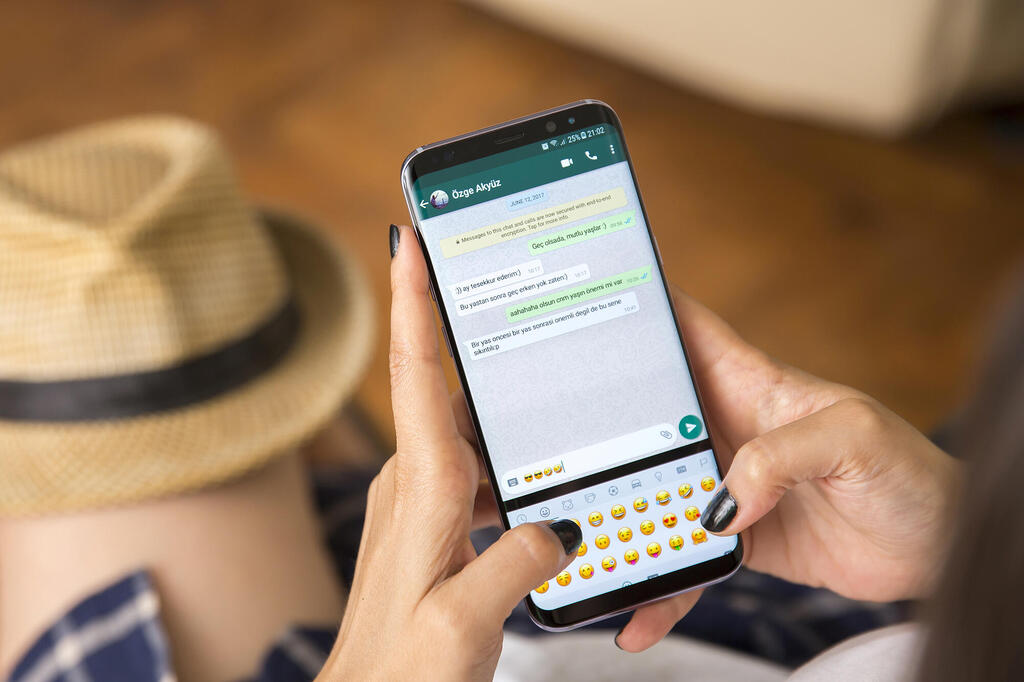

Meta's compliance was mandatory due to its possession of the data. However, this raises the question of why the company had possession of such data in the first place. Messenger is among the few major instant messaging services that lacks end-to-end encryption (E2EE) technology. Twitter also falls into this category, with its employees having been exposed to users' messages on the platform both actively and passively over the years.

Today, the greatest challenge to user privacy comes from governments striving to mandate technology companies to provide a "backdoor" for access to personal conversations in messaging applications. The most advanced legislation in this regard, supported by major industry players, is the British "Online Safety Bill," currently awaiting a vote.

This complex and comprehensive law addresses various important issues, including Section 110, which requires websites and applications to proactively prevent harmful content in messaging services. The legislation grants regulators the option to employ scanning technology (if available) to examine user communications and identify prohibited content. Based on the findings, various actions can be taken. The concern is that the legislation in the UK will establish a legislative precedent that other governments worldwide may follow, significantly undermining end-to-end encryption.

An open letter signed by the heads of seven messaging applications, including WhatsApp and Signal, stated, "If implemented as written, [this bill] could empower Ofcom to try to force the proactive scanning of private messages on end-to-end encrypted communication services — nullifying the purpose of end-to-end encryption as a result and compromising the privacy of all users. In short, the bill poses an unprecedented threat to the privacy, safety and security of every UK citizen and the people with whom they communicate."

End-to-end encryption (E2EE) technology safeguards user privacy and security by encrypting digital communications, ensuring that only the sender and recipient can decrypt the messages. This means that even service providers like WhatsApp, Signal, or iMessage cannot read or listen to conversations. This technology already exists and is the default setting in many applications, enabling billions of users worldwide to communicate privately and securely.

While the British legislation is among the most advanced and comprehensive in addressing this technology, it is not the only one. In April, the United States introduced the federal bill "STOP CSAM (child sexual abuse material)" to protect children online. This legislation creates an exception to Section 230, which grants partial immunity to internet intermediaries for user-generated content related to child exploitation. The proposed bill holds technology companies civilly and criminally liable if their products are used to "promote or facilitate" crimes involving child exploitation and other offenses. It also requires companies to submit annual reports to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), detailing the means and technologies they employ to protect users and any factors that may hinder their ability to identify instances of child exploitation.

According to the American digital rights organization the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the terms "promote" and "facilitate" are broad and allow for low-standard accountability. Such broad wording may lead to a surge of lawsuits by victims of child exploitation filing claims against tech companies. Consequently, courts may have to address questions like whether Signal facilitates child exploitation by defaulting to end-to-end encryption or whether Apple contributes to it by offering the application in its app store. Opponents of the law argue that these options provide sufficient room for negotiation and could incentivize tech companies to weaken encryption, compromising digital security for all internet users.

In the European Union, efforts are also underway to promote CSAM legislation. Proposed in May and currently in the legislative process, this regulation mandates instant messaging applications to install monitoring software that scans images and conversations based on a secret database. An independent entity overseeing the process determines the content and criteria for searching, and if prohibited content is detected, it must be reported to the authorities. This legislation not only compromises end-to-end encryption but also enables governments to directly access personal information.

Proponents of these various legislations claim that they are necessary to protect children. "We support strong encryption, but it cannot come at the expense of protecting the public," said a British government spokesperson in a statement. "End-to-end encryption cannot hinder efforts to apprehend the perpetrators of the most serious crimes." A leaked document from the European Commission in May, responding to the Commission's legal advice on the proportionality issue, stated that "the Commission believe that there are many elements which, especially when considered as a whole, justify the conclusion that the proposed search warrant system is proportional."

Civil organizations working in this field argue that existing encryption is not only vital for the fundamental right of individual privacy, but also serves as essential protection for the most vulnerable. They explain that it prevents personal information from falling into the wrong hands, especially for children, and enables human rights activists to operate in hostile environments. Moreover, providing a backdoor for accessing private communications creates a significant information asymmetry between governments and citizens, potentially increasing surveillance and control, leaving citizens more vulnerable to cyber attacks, and ultimately failing to address the problem of child exploitation.

Signal President Meredith Whittaker, in discussing the British bill, told the BBC, "It's magical thinking to believe that only the good guys can have privacy. Encryption protects everyone or it is broken for everyone."