Interview

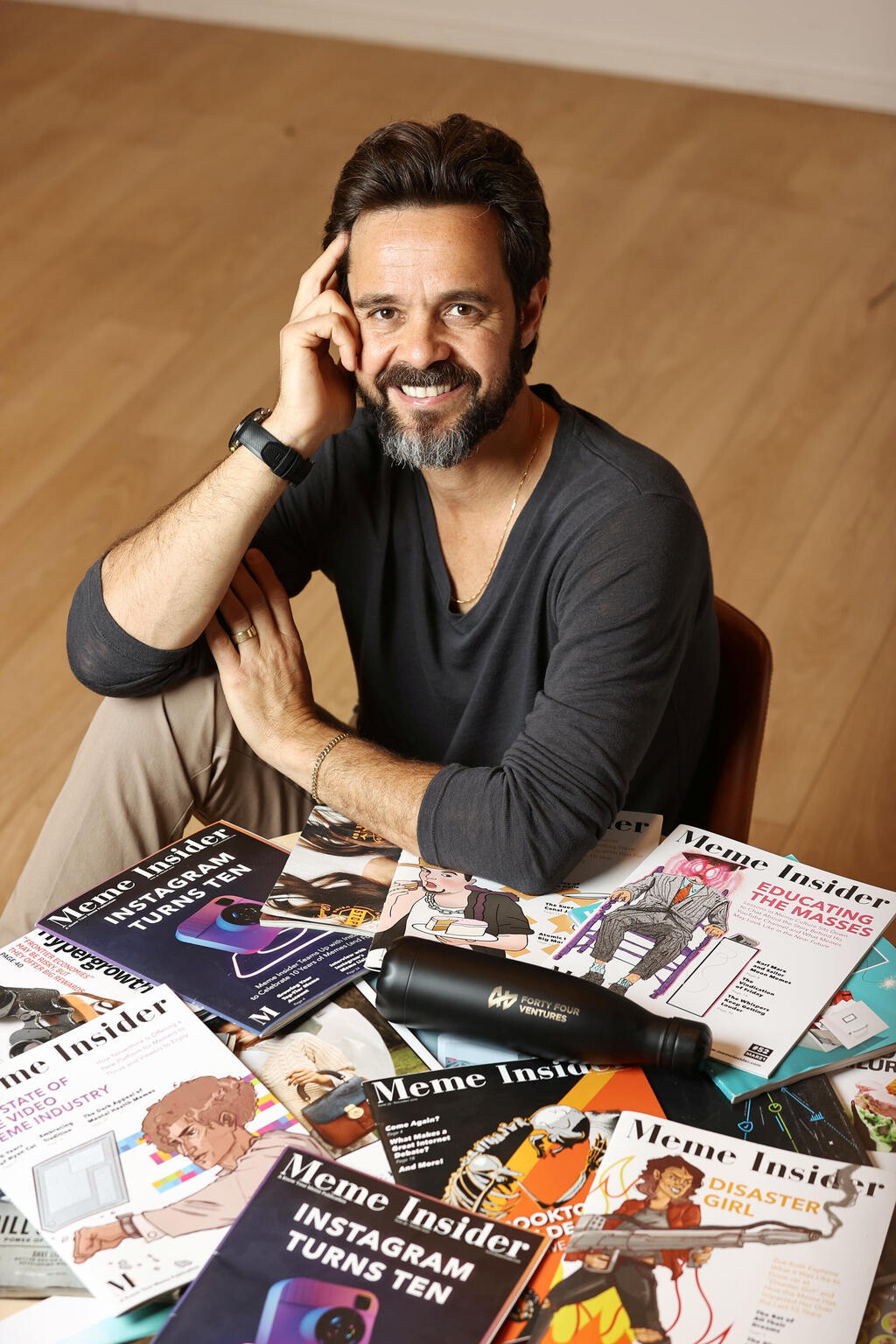

The Israeli Meme Insider selling Americans their own humor

Kobi Nizri has built an empire of American comedy, making money off viral parody clips, memes, and more. He discusses how he generates revenue from cute cat pics, how not to offend an American audience, and how it all ties back to his childhood in the peripheral town of Ramle

“I’m the least funniest person alive,” admits Israeli comedian Jacob (Kobi) Nizri in an interview with Calcalist. That’s a surprising revelation for someone who’s built an entire empire of comedy websites - whether that’s funny videos, memes, or comedic pieces - who runs Literally Media, a group that has 40 million users a month, and according to Comscore, is rated as the most popular group in the humor category in the U.S. Nizri is on a mission to give Americans a dose of their own humor.

How does someone who’s not funny end up working in a business that’s all about humor?

“It started out as a business interest. While I don’t consider myself funny, I can appreciate good humor. My childhood friends back in Ramle are hysterical. I’m the serious guy in the group, who people come to ask for advice. It’s funny that I was the one who discovered this side of humorous content - somewhat randomly - but I’m very proud of it. In a bombastic sense, we provide people with everyday relief. Our content is meant to make you feel good. Clearly, we earn money from it; we’re not suckers. Our goal is to give our users a five minute food-for-thought break, and if we succeed: wow!”

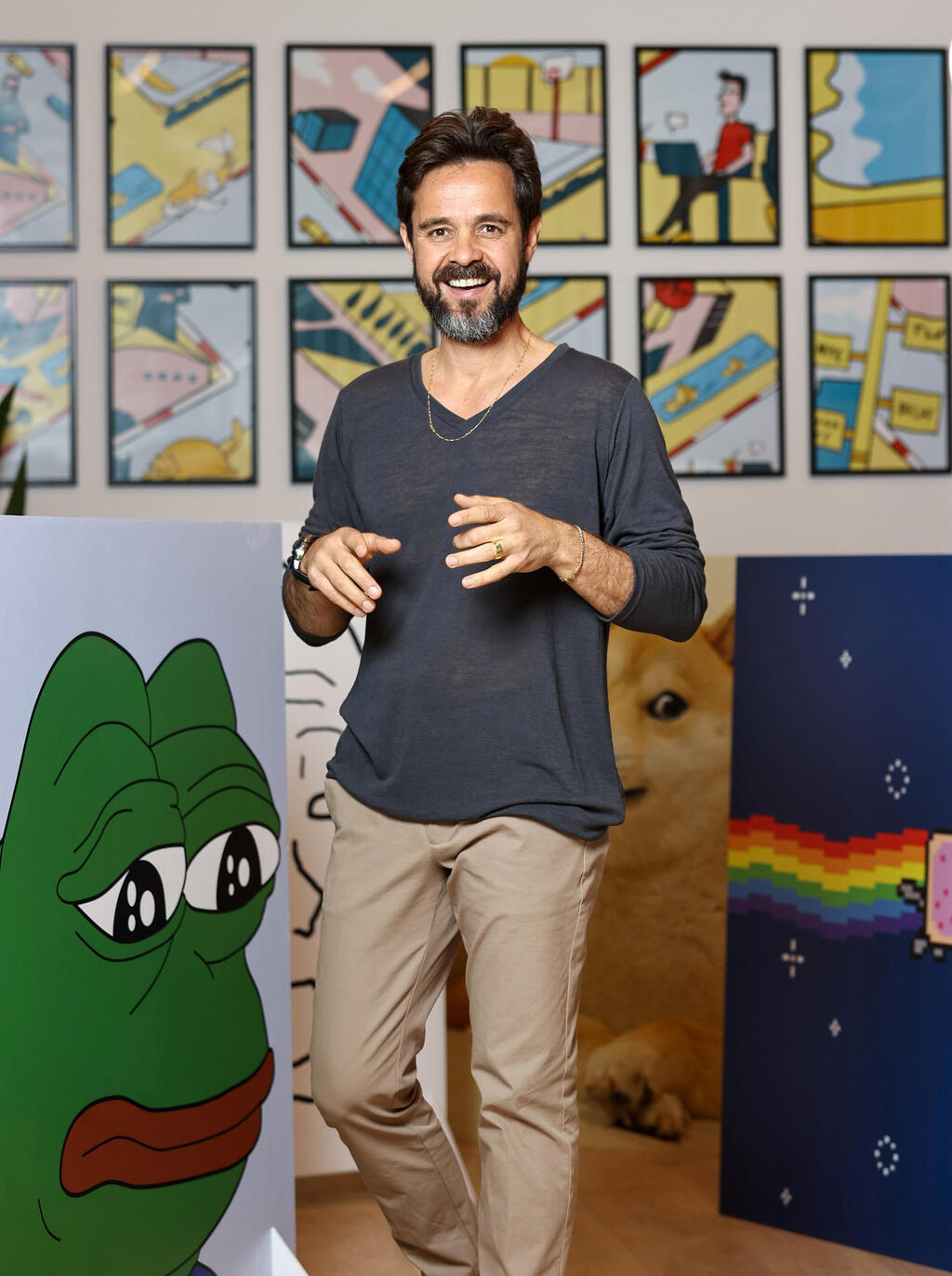

The expertise of Nizri’s websites is creating viral content, oftentimes generating a countless number of items which are then re-shared on social media. That could be cute pictures of pets and animals, to a top-20 list of the biggest fashion failures at the Oscars, amusing memes, images accompanied by a punchline, or parody clips on cultural references. In Israel, the meme culture hasn’t taken off yet like in the U.S., but there are some popular humorous Instagram accounts and Facebook pages. In the U.S., however, there’s an entire industry of comedy sites, with each one targeting a certain group or type of humor.

Literally’s brands include popular sites that are considered a core part of American humor, including “I Can Has Cheezburger,” which was one of the pioneers of cat-centric memes; “Know Your Meme,” a Wikipedia of online culture and viral phenomenon, which is also behind Meme Insider, and eBaum’s World, a site built on user content that has been around since 2001.

The second surprise regarding Nizri is the fact that his very U.S.-centric comedy empire, which has 80 full-time employees and 40 freelancers, and generates 2,000 new pieces of content per month, is managed from Herzliya. “I’m really proud of the fact that most of the content is created here,” he says. “Israel is a major exporter of tech and media, so there’s no reason why we can’t sell viral content as well as TV series’.”

How can an Israeli manage something as local and cultural as American humor?

“It’s really complicated, and it took us a long time to find the right equation. In the beginning, there was plenty of doubt, especially since I came in as an Israeli and started telling American content creators that I get their humor better than they do. It led to arguments.

“Last year, we had a management consultation, where one of our main goals was to rebuild the bridge between Herlizya and New York. What worked in the past wasn’t enough. The Americans feared an Israeli-takeover, and also were frightened by Israeli pressure, and our ability to make snap decisions, sometimes without prior approval. We also struggled a bit with the American corporate management culture, where everything is organized but the decision-making process is super slow.”

How did you overcome your cultural differences?

“I think that the moment they realized that our Israeli team is full of content creators who have a background in big data, they started listening. They realized that our challenge - what type of content site visitors see - will help them in the long term. They also saw the numbers - all the sites we bought were money drainers, until we optimized them. We also ran an aggressive campaign on social media (on Facebook alone, Literally has over 8.5 million followers, RD).

“On the Israeli side, we had to realize that the American content creators were right, we had to ask beforehand what changes we wanted to make, and get their blessing. This content is deeply rooted in American culture, and that’s why it was important to clarify that Israelis aren’t competing with Americans over content. It’s not our playground, it’s theirs.

“In the end, we agreed that the Israelis can respond, criticize, and be involved in the content creating process. We taught the Americans that they’re allowed, and oftentimes even encouraged to disagree with their managers. We taught them how to say ‘no.’ And we also learned to talk slower, to examine things for a bit longer, and to be more organized. Now, our U.S. team even knows a few words in Hebrew.”

Why did you decide to run the company from Israel? The majority of your targeted audience is American.

“For me personally, it was important to me to operate from Israel, and not the U.S.”

Why?

“Because I’m an Israeli patriot, but I’m also a business guy. Loving Israel is a wonderful thing, but if it doesn’t work out business-wise, I’d find something else.”

How can an Israeli make an American laugh without offending them?

As part of the streamlining and outsourcing of the comedy sites, Nizri has added a few Israeli comedy experts to his team, including TV creator Moti De Piccioto, Tamar Sukenik, formerly of Walla news, and Itzik Shasho, formerly creative director of Ynet’s commercial content department, and others.

How do you overcome cultural gaps when you’re creating content - like funny memes - that only Americans will understand?

“First of all, we aren’t the only ones doing this,” clarifies De Piccioto, who oversees social media and SEO Operations. “For example, the entire team of Bored Panda resides in Lithuania, even though most of their editors are from England, they also hire locals. We also have some operations in Israel, but most of our team, close to 75%, lives in the U.S.

“Our first attempt at creating content was with Cheezburger (which generates content for young women and teenage girls). Our offices are in Seattle, and when we needed more content people, we decided to recruit them in Israel and not in the U.S. Obviously, there were some concerns. We didn’t just buy the business and say, ‘we’re moving our offices to Israel because we know how to do our job better than you guys.’ We’ve hired a lot of local talent in Israel, especially people who made aliyah from the U.S. We’re looking for people who are proficient in the content world of American culture, know their memes, know what stuff works and what doesn’t, and how to write well.”

What’s the difference between American and Israeli humor?

“The issues are constantly changing based on cultural differences,” said Sukenik, the editor-in-chief of Cheezburger. “There are entire categories of humor that Americans like and Israelis haven’t even heard of. The transition from childhood to adulthood has generated millions of memes, funny quotes, and jokes in the U.S., because ‘adulting’ is sort of a gray area. But in Israeli culture, once you complete your mandatory military service and are released from the army, you’re already an adult.

“Another type of content that occupies a serious share of American online culture is ‘wholesome’ - a word which has no real equivalent in Hebrew. It’s heartwarming, feel-good, and comforting. It isn’t well-known in Israeli culture, but in New York I came across women at cafes who surf through cat lovers’ sites, and say: ‘I got my dose of serotonin for today.’ And when it comes to coffee, they also love memes about ice coffee, but that’s an entirely different topic in itself.

“The biggest difference between Israelis and Americans is meme culture. In Israel the format is pretty new, while in the U.S. even older adults are familiar with memes. They grew up with them, and use them naturally, they even make their own and share them not just to be funny but as a form of coping with an emotional issue. That isn’t something that I’ve encountered in Israel.”

Are there do’s and don'ts in writing content for Americans?

“Israelis are more straightforward and blunt with our humor,” De Piccioto explains. “But when we try to appeal to broader audiences, the minute you cross a red line - even slightly - it’s a lot harder to deal with the repercussions afterward. I would expect there to be more tolerance for daring humor after sitcoms like Seinfeld and even the amount of American comedians who make jokes about being politically correct, but it doesn’t really work. You need to know how to tread lightly. The biggest taboos are like those in Israel: any issues about religion, ethnicity, gender, and shaming. The difference is in where those red lines are, and in order to understand where the boundaries lie you need to understand U.S. culture firsthand.”

Do some types of humor work better?

“There isn’t any clear equation which type of humor works better, and it’s also something that changes constantly. I’m always surprised how nonsensical humor always works - things like wordplay and double meanings. Once a month we have a meme on Facebook that reaches between 30-40 million people with hundreds of thousands of shares. Sometimes, it’s really funny but other times I don’t really get why people think it’s so funny.”

Does Israeli and American humor have much in common?

“Since the Trump era, U.S. humor looks a lot more like Israeli humor. Beforehand, there might have been more sensitivity, but that all disappeared and now American discourse looks a lot more like Israeli discourse - and that’s not necessarily a good thing. Now, society is a lot more divided, which reflects what is happening in Israel.”

From rags to riches

Today Nizri lives with his wife and four children in Ramat Hasharon, but his story starts much earlier, back in Ramle, where he was the middle child of a hairdresser mother and a father who worked for national water company Mekorot. “I had a lovely family-centered childhood,” he says. “My mother worked constantly but was always within eyeshot. I would wake her up when customers would drop by at 8:30 a.m. or during the afternoon hours, and help her out.”

Ramle is considered a difficult city, especially during your childhood.

“I didn’t feel it back then. We were raised to excel, and were taught that we could do anything. When you tell people you live in ‘Ramle’, and they think it sounds like ‘Ramallah’ you realize how society's perception of the town isn’t so positive. We lived in one of those plain two-story houses with four tenants. My childhood was split up between hanging out at home, at my friends’ houses, and in the Israeli scouts. We didn’t take too many vacations, but we weren’t unfortunate either or were lacking in any way.

“On the other hand, when you leave and see other towns in Israel with fancy villas, you start to ask yourself where you really want to live? Or why other people are so well-off and you aren’t? You want to believe that one day you’ll live in someplace like that too, that you’re just as good as them. It isn’t jealousy, but proving that you have that ability to make it.”

And Nizri more than proved himself. In the military, he was an officer in the Armored Corps, and later pursued a double-major in teaching (computer studies) and business management at the College of Management Academic Studies in Rishon Lezion.

How did you have the funds to study at a private college?

“The Ministry of Education gave scholarships to those pursuing double majors - such as teaching computer studies - and covered nearly all my tuition. The rest I covered through a scholarship I received from the Ramle municipality.”

Nizri’s entrepreneurial spirit was expressed from early on in his college days. “During my academic degree, I started a small company that taught people how to use computers. We’re talking about the early 2000s, where there were a lot of industrial facilities with older managers who didn’t know how to use that device that sat on their desks. I would travel to them, and explain it to them and transfer all their documents to Excel or Word. I had a family member who worked at Microsoft and they looked for someone who could help them out and give lectures on how to use the new version of Office, so I did that as well.”

It must have been tough as a 20-year old to give up your job security and dare to embark on an entrepreneurial dream.

“I wasn’t afraid. Maybe it’s because my dad lived like that. He was driven by this desire to have a steady and safe position, and yet we constantly lived in existential tension, where we were always wary of not reaching a state where things were scarce. So I developed a response against that. And that tension, which was always alive within me, turned into a sense of awareness and hunger for more.”

Toward the end of his degree, Nizri met Ofer Druker, one of the pioneers of the Israeli digital advertising industry, who took him under his wing. “We spoke for six months, and I didn’t really get what he did in his business, until one day he said ‘come with me,’” says Nizri. “His company, Oridian, operated out of the U.S., and his idea was that I’d expand the business into the international market. The work suited me just fine, and I took it on as a student night job. I got a small computer, and started doing proper marketing, sales, and business development. Later, Ofer took me with him to Europe and I joined in on his meetings. I learned so much from him.”

A year later, Druker left the company, and Nizri - who was only 26 at the time - was promoted to VP. “It was one of those high-tech environments back in the day, and I was still that kid from Ramle, and didn’t fit in,” he says, diplomatically, hinting that his promotion didn’t go over so well with the rest of the company. “But I was very goal-oriented, and I didn’t let it get to me.” In 2006, right before he turned 30, he was appointed as CEO. And a short time before the markets collapsed during the U.S. recession, less than two years later, the company was acquired by Ybrant Digital.

Since then, Nizri took on a number of roles in the media and founded a few companies, such as Positive Media, a platform that promotes positive reviews online and deletes negative ones, which was later acquired by Ynet in 2018; Twist Digital, a platform for independent content creators to promote and market on social media networks, where he continues to serve as co-founder and chairman, and MindAd Media, which specializes in segmented marketing, where he also serves as chairman.

How did you go from advertising to creating funny memes?

“In advertising, my job was sort of like a broker’s: I was the link between the site and the advertiser. In that food chain, the site owner is at risk, because the advertiser charges them a lot. I spotted great potential in this market, and decided to acquire digital assets - just like real estate, where you buy buildings with tenants, evict them to remodel, and then take on newer tenants who pay you more because your product is better - that’s what we did in terms of content.”

So why did you choose humor?

“We did some research. We started out with sports and then branched out into a few different areas, until we reached entertainment and looked at the numbers, and were shocked. Then an opportunity came along through eBaum’s World, whose numbers were good but was losing money, and somehow its ownership was up for grabs. We acquired the first site, and then quickly acquired the second site as well, and so forth. We were looking for assets that were at a crossroads or struggling financially, because back then we didn’t have the ability to finance growing businesses.”

What does an Israeli advertiser understand that American content experts don’t?

“As someone who came from the monetization side, I know how to maximize any asset to yield maximum output. Literally’s profits stem from three different channels: our first and main channel is advertising banners (whether images or videos), which are located on our sites; the second is actual video clips - anything I upload to our YouTube or Snapchat channels - the site adds embedded advertisements and shares the income with us; and the third is insights services that we provide, which are based on our data capabilities and enable us to give groups, like advertising agencies, advice on a periodic basis, such as what’s trending right now, which will help them produce their next content.

“Aside from that, we had a lot of work in optimizing the sites we acquired. We suddenly saw a crazy picture, where sites employ a lot of American VPs who earn too much, when they can do it for less in Israel or elsewhere.”

Making dreams come true

As impressive as it is, Literally Media is only a small part of Nizri’s success story. In 2015, he started his own private investment firm, WeEndeavor, which he also manages, and is involved in around 15 different companies, who employ 250 people in 10 different countries. His fund has invested in companies like Convert Media, which was acquired by Taboola in 2016, and owns shares in eXelate, which was acquired by Nielsen International Holdings, Inc. in 2015 for $200 million.

“That hunger and fire within me doesn’t ever go away," said Nizri, who is also a member of the YPO program for Young Harvard Leaders. “I’m constantly thinking about the next task, and am busy trying to prove the next big thing. For years I didn’t stop to relish in my experiences or pause to be happy about my achievements, I simply plowed forward. Now, I know how to better appreciate these things. It comes with age and is a matter of maturity, but is also part of change - I’ve been taking a step back from working and spending more time with my family. Learning to calm down and let loose more often.” To that effect, last month Niziri appointed a new CEO at Literally, Oren Katzeff, who is former president of the Conde Nast Communications Corp.

That break has also allowed Nizri to delve into taking more social action. Since 2014, he has been a board member of Tapuach, an organization that works to promote digital equality in Israel through hands-on tech training in peripheral towns, by teaching the elderly how to use the internet, subsidizing high-tech training courses, and supporting a digital youth movement. Over the past few years, Nizri has devoted a lot more time to the organization. “I clicked right away with Dafna Lifshitz (the former CEO), mainly because she talked about the groups’ youth organization - which is called Neta@ - and also mentioned by chance that one municipality is willing to donate its building to the organization's needs - and that it happened to date all the way back to the period of the British Mandate. That city was, of course, Ramle. I felt like somehow everything was connected.”

Nizri also recently changed the name of his fund - which employs his old childhood buddies from Ramle - from WeEndeavor to 44 Ventures. He decided to name the fund after Highway 44, which connects Ramle to Tel Aviv. "To me, that number represents making friendships with good people," he explained. “We are active investors in startups that have a certain twist - we help create the companies with the entrepreneurs themselves. My goal is to help out the young guys - not the fancy entrepreneurs who want to manage big venture capital funds, but those who need that extra boost. I call them 'unpolished diamonds.' They can be VPs in companies that want to take the lead, but aren’t daring enough to do so, or those who live in peripheral towns, who get less chances with big funds because they are more direct.”

How does that work?

“I work as the chairman of those companies’ and help them out. My partner, Yaniv Ben-Atia, is their tech guy. He used to work at Microsoft-Israel, where he previously served as CTO, and is also a good childhood friend of mine from Ramle. He accompanies their teams from the very beginning, whether that’s helping them build their infrastructure, starting out with IT-level tech to reaching a more hard core level of technology, helping them recruit their first developers and accompanying that first team until it can stand on its own. Our third partner in the fund, Shirley Lowenstein, is responsible for researching the field we’re entering, collecting data, and examining the venture's business feasibility.

“My other childhood buddies at the fund include Shahar Shaharabany, our CFO, who provides financial services to all the companies, and Daniel Ravner, who provides the companies with external marketing consulting.”

In the end, it all goes back to Ramle.

“Yes, even Amit Tapiro - who’s a partner of mine on several companies - we realized we had grown up on the same street in Ramle, just a few houses apart. Our grandmothers even lived next door to each other.”

So your goal is to show to people in Ramle that they can make it big?

“I’m a big believer in starting out small and giving people chances. It’s something that I’ve carried with me since childhood - to make people realize that you can make your dreams come true, even when everyone else tells you ‘no,’ or that you aren’t in the right place or aren’t the right person. Our mantra is: try, what’s the big deal? Worst case, you’ll fail. That’s how we founded seven companies, and a few more that we later sold.”

Is the high tech industry the solution to the socioeconomic inequality in Israel?

“Not necessarily. I’m not one of those who think that everyone needs to serve in Unit 8200 (an intelligence unit in the Israeli military) to make connections. My goal is to instill in those who live in small towns that they can dream big too. My experience growing up in a small town left me with a fear of being told to work somewhere safe and boring, only not to fail. And that’s what I want to change. People need to try. Worst case scenario? Nothing will happen, but you’ll learn a thing or two that will help you or even carry you to your next position. I don’t think that everyone should be an entrepreneur, but everyone should have internal entrepreneurship and anyone can dare.”