WeWork’s Next Challenge: Get Off the Steroids

SoftBank invested over $10 billion in WeWork, enabling the company’s meteoric growth—and its massive debt. The successors of ousted CEO Adam Neumann will need to halt that growth and even start pruning if they want the company to last

14:0926.09.19

The outwards drama at coworking giant WeWork may have come to a close with the ousting of co-founder and former CEO Adam Neumann, but the hard work is only starting. Exposing the inner workings of a company as part of an initial public offering without going through with the fundraising is one of the worst things that can happen to a company, and WeWork will have to persevere.

The entire world is now aware of WeWork’s numbers, and has come to the realization that there is not much behind it that differentiates it from competitors like Regus, which has a much more modest valuation of $4.5 billion. Worse, everyone now knows that WeWork is in dire need for cash, and a lot of it. CEOs and investment banks like to spout the motto that you raise money when you need, not when you can. WeWork really did need the money, and hoped to capitalize on the tech IPO hype of 2019, which saw giant IPOs like Uber, Lyft, and Slack.

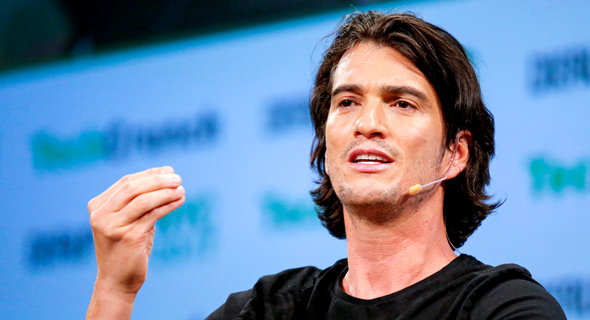

WeWork co-founder and former CEO. Photo: Reutersצילום: רויטרס

1. WeWork: things are going to get worse

According to its prospectus, WeWork had $3 billion in its coffers at the end of the first six months of 2018, but given the rate of its cash burning, this is not a high sum. The company’s expenses surpassed $1 billion a year for the past few years, so at best it will be enough for two years of operations. However, Wall Street estimates that taking into account WeWork’s debt repayment requirements, the company has a year of cash at most. The main challenge that new co-CEOs Artie Minson and Sebastian Gunningham will face, then, is stabilizing WeWork financially.

To make matters worse, the company—which until recently enjoyed the glamorous image of a tech company that invented the coworking concept—revealed its weak spots in its public prospectus. And they aren’t any different than the average real estate company operating today, except that in WeWork’s case, a real estate company on tech company steroids, those weak spots are 10 times worse.

The $10 billion SoftBank infused into WeWork since 2017 enabled the company to grow meteorically, while also collecting unchecked, massive debt. The company has minimum future lease obligations of around $47 billion, and that’s a lot for a real estate company, no matter its growth rate, especially considering WeWork ended 2018 with $1.8 billion in revenue and a loss of $1.6 billion.

Potential investors were not the only ones made privy to WeWork’s inner workings following the publication of its prospectus—both landlords and tenants were looped in as well. WeWork’s model is based on the very low-risk difference between the very long leases WeWork signs, and the more expensive short leases tenants sign. WeWork also puts money into renovating its co-working spaces. Its business filings reveal that the company learned to balance its expenses and revenue only recently, and until then basically subsidized its operations with SoftBank money.

Both landlords and tenants now understand they have leverage on the new management. The tenants, especially WeWork’s corporate clients, understand that they can pressure the company into lowering its rates, though that holds true mostly for WeWork’s still unoccupied locations—which the company has a lot of. In its prospectus, WeWork prided itself on 40% of its tenants being companies of over 500 people, but now having so much strong customers is a double-edged sword.

With no short-term strategy for raising money, WeWork’s new bosses understand that to maintain financial stability, the company will need to take a step back from the SoftBank-mandated expansion rate that encourages companies to take over the market without any consideration for the bottom line. With a $700 million debt to bondholders in the U.S. and bonds that entered junk territory a while ago, and a $500 million debt to a banking consortium, WeWork’s management will need to consider its profit margins much more now. It is therefore unsurprising that since Tuesday, more and more news outlets have reported the company is heading towards extensive cutbacks of its 12,000-person workforce.

2. Adam Neumann: I or We

As Minson and Gunningham drafted their announcement, Neumann—who founded WeWork at the age of 30 and became a superstar even compared to other unicorn founders—wrote his own declaration. Ironically, his main motive was, once again, the divide between I and we, the same issue that drove away so many investors when the prospectus was published. “In recent weeks, the scrutiny directed toward me has become a significant distraction, and I have decided that it is in the best interest of the company to step down as chief executive,” he wrote.

Those were the words of the same man who licensed the use of the name “We” to the company for $5.9 million. While he hurried to return that sum to the company following the criticism the revelation drew, it was just the beginning. The entire prospectus read as Neumann’s social-philosophical manifesto, intermixed with hints of a personality cult for the co-founder. Now SoftBank could be seen as trying to distance him from the company with what seems like directed reports intended to assassinate his character, bolstered with “hints” that SoftBank founder and CEO Masayoshi Son opposed much of what was written in the prospectus.

Neumann’s dethroning included cutting down his voting rights. Reports in the U.S. seem to suggest that he will lose most of his WeWork options, and that his wife Rebekah will leave all of her roles in the company. This is a complete ousting for the Neumanns, as in the original prospectus, Rebekah had the authority to choose her husband’s successor should anything happen to him.

The big question both WeWork’s employees and its potential investors should ask themselves is just how central Neumann was to the company. Just a month ago, the company dedicated a few hundred pages to explaining how Neumann is the predominant force at the company and has the final say on everything. Now they are being told he is the root of all of WeWork’s problems. The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle.

At the height of the financial crisis, only someone with a vision and Israeli “Chutzpah” like Neumann could have dared to take rundown buildings, renovate them, and market them to the tech sector as sexy coworking offices. But similar to many other companies—and in this aspect WeWork is indeed like a tech company—a decade after its foundation, WeWork needs someone else who will be able to take it from an amazing idea to a financially sound business. Neumann, unfortunately, is not that person.

3. SoftBank: a model or a bubble

SoftBank really needs to sit down and have a deep think following the events of the past month. The investment giant has become the tone-setter for the tech sector in recent years, but the past year has put it through the wringer, especially considering it is currently attempting to raise a second fund of over $100 billion. For SoftBank, WeWork is not just another bump in the road, but a hit threatening to take the air out of the bubble known as the investment model of Japanese genius Masayoshi Son. His perception as a genius was built mainly on the basis of one famous investment—the $20 million he betted in 1999 on a young company called Alibaba, an investment worth over $100 billion today.

In recent years, however, many an eyebrow has been raised over Son’s investment choices. Suddenly they were not measured in the millions but in the billions, creating what has become known as the SoftBank effect: massive investments that give startups inflated valuations and flood them with cash while pushing out more solid capital funds who do not believe that the ends always justify the means.

Most of the companies SoftBank backed in the past two years underperformed. The biggest disappointment is Uber, which went down 25% since its IPO at the beginning of the year. The price tag SoftBank gave WeWork at its last funding round, $47 million, has also proved to be lightyears away from the valuation Wall Street was willing to sanction. Though most of SoftBank’s investments are still profitable, it might find itself forced into recording down rounds that will harm the returns its mostly Gulf States investors are expecting.

The biggest threat is the creation of a new SoftBank effect—the realization that too much money has been invested too fast in tech companies, especially those operating according to the new sharing economy models that do not own assets of their own and grow quick without any reliable profitability model. SoftBank has another real estate company in its portfolio, New York-based real estate company Compass Inc., also founded by an Israeli, which have already reached a valuation of $6.4 billion thanks to SoftBank’s investment.

But the ultimate test for just how much investors are willing to swallow the unicorn hype will take place in 2020, when Airbnb is expected to list. The company’s latest round valued it at $35 billion.

4. First Travis Kalanick, now Adam Neumann: investors are starting to wean themselves from the myth of the founder

WeWork and Adam Neumann’s rapid fall from grace represents a line in the sand as far as the rehabilitation investors, the market, and the entire tech ecosystem are undergoing. It is a rehabilitation process from two dangerous addictions: the shiny front that media-hyped startups present, and the charismatic founders that head them.

WeWork’s management was caught by surprise by the response to its prospectus. They expected investors to show the same enthusiasm they showed for Snap, Uber, and Lyft. Those companies also reached the market with immense valuations, immense losses, and no strategy to become profitable in the future.

But the same investors have learned their lesson. They saw Snap’s, Uber’s, and Lyft’s stock plummet after their IPOs. It seems the market has realized that a popular product that sells isn’t enough, and that if the company is reporting mostly losses, there is no reason to take it at its word when it comes to valuation, especially when it is not at all clear why WeWork has decided it is a tech company.

Related articles

At the same time, Neumann’s plummet signifies that Silicon Valley is separating itself from the decades-strong myth of the visionary, strong founder—men like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos, who have led their companies to dizzying heights and were integral to their successes. That is why when Facebook listed, few were put off by its unusual control structure, which kept most of the power at the hands of founder Mark Zuckerberg. The company’s subsequent success seemed to justify the model, which was adopted by companies like Snap and Lyft, despite recent cracks that highlighted Facebook’s problematic managemental culture.

The most well-known case of a founder who fell from grace is Uber founder Travis Kalanick, who created a toxic working environment and did not hesitate to follow dubious tactics to strengthen Uber in different markets. Eventually, the scandals were big and widely-reported enough to have Kalanick ousted before the IPO. It seems the lesson taught by Kalanick, Snap, and others has left a big enough impression on investors, who took one look at Neumann’s behavior and said “no more.”