Analysis

Unlike Europe, Indian privacy law is skewed in favor of Google & Amazon

The new Indian law for the protection of digital personal data prioritizes the interests of the government and private companies over the protection of surfers

India has joined a handful of countries that have passed advanced privacy protection legislation. The upper house of the Parliament recently passed the "Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023" (DPDP), its fifth draft, which will come into force after the signature of Indian President Droupadi Murmu, which is expected in the coming days. Among other things, the law establishes obligations for those who hold the data, provides protection measures for children's data and rights for individuals, allows the transfer of data between borders, and establishes financial fines and a system for managing complaints.

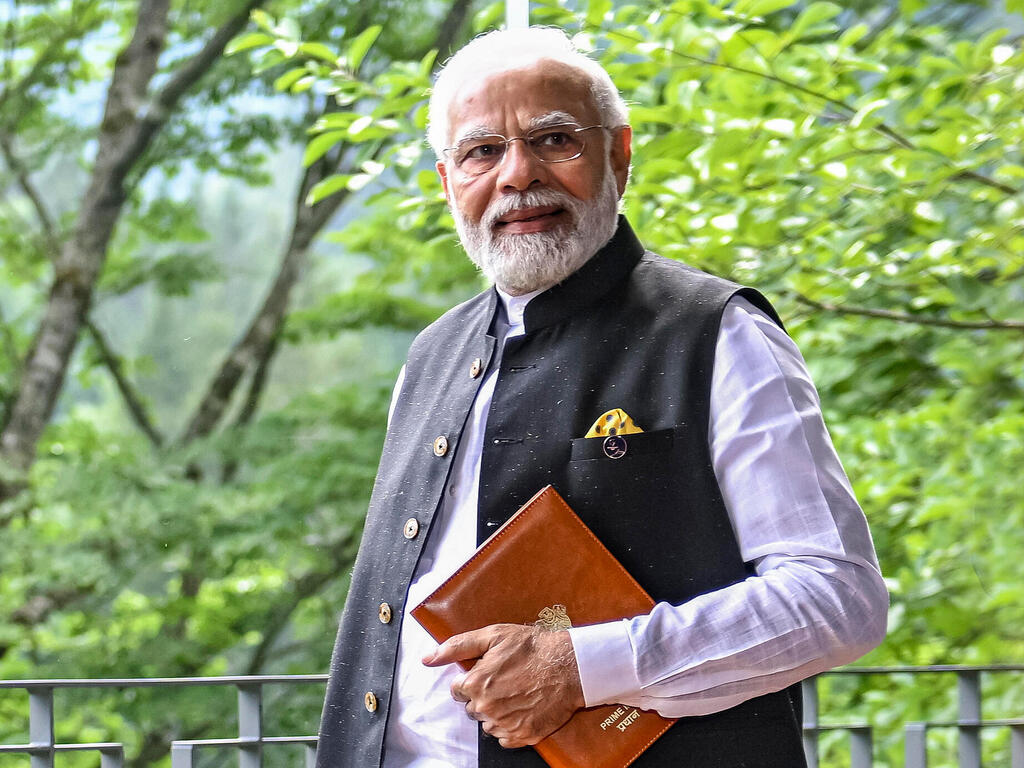

"We live in an age where we find ourselves in the digital world more than ever before," Electronics and Information Technology Minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar said this month. "There is an environment of large companies, small companies and technology companies that create business models by abusing and exploiting digital personal data of citizens. This is something that this bill intends to address," he emphasized.

In some ways the legislation does address a number of urgent issues, especially in a country that has never had specific legislation on the subject. It defines and limits companies operating in India or processing data on Indian residents, as well as when the data can be collected and used. Also, the law requires the companies to obtain consent for this purpose and to stop processing the digital personal data within a reasonable time frame, if the consent is revoked.

The law defines what is the "consent" required for data collection and guides it to be obtained in simple language. It also defines the obligations of the collection, including deletion of information within the "right to be forgotten". Companies that do not comply will be exposed to heavy fines of up to 2.5 billion rupees (about $30 million). It was also determined that the government will establish an information protection council that should ensure compliance, impose penalties and serve as an outlet for public complaints. Council decisions can be appealed to the High Court within 60 days.

Work on the law began when the Supreme Court of India ruled in 2017 that there is a basic right to privacy. In 2019, a first framework was built and passed in parliament, and during the public comments phase, it received more than 20,000 comments from interested parties, including the technology giants Amazon, Google and Meta, who claimed that it would impose too great a burden. Following the pressure, the Indian government withdrew the bill and began working on a business-oriented version. Last year it presented DPDP 2022, and in November the draft was opened for public comments. This month a proposal was submitted for a vote in the houses of parliament, but of a new version. This was the first time the members of parliament saw the proposal, which was fundamentally changed compared to the 2022 version and did not pass the public comment stage. Despite this, the government acted quickly, the lower house passed the proposal in 51 minutes, and the upper house in another 68 minutes, without objections or amendments - this is because the opposition left the plenary hall in protest and did not vote.

The legislation was supposed to be good news to about 900 million Indian Internet users - a basis for promoting a comprehensive data protection regime. But the wording of the law, as well as the way it was passed, drew strong criticism from the opposition and social organizations. The criticism concerns the fact that the proposal does not address the protection of information for the benefit of the citizen, but its purpose is to balance the basic right to privacy and the desire to utilize data as much as possible for various uses by private companies and the government. This bias is present in the first sentence: "An Act to provide for the processing of digital personal data in a manner that recognizes both the right of individuals to protect their personal data and the need to process such personal data for lawful purposes and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto." From this it follows that its first purpose is not to protect private information, but to explain under what conditions companies can process the data.

This approach is quite different from the one that exists in the European Union under the GDPR privacy legislation. According to the GDPR, companies can export data of EU residents only if and when the party to whom the data is transferred complies with the mandatory rules. In Indian legislation, on the other hand, data can be transferred to any country, unless India determines otherwise. That is, the legislation significantly eases the compliance required from companies such as Google, Amazon or Facebook, which operate widely in the country. Not only that, the legislation allows granting "exemption" from compliance to certain companies, at the government's discretion, including the freedom to collect data without user consent for "certain legitimate uses" and their exclusion from collecting data on children. The legislation gives the government broad discretion to determine which countries can be transferred data, and even provides legal protection to the government and the Information Protection Council.

The government also reserved the authority to exempt any government entity from the application of the law and removed the state's obligation to disclose information if there is a "public interest" in doing so (based on legislation from 2005). These concessions, in particular, provoked criticism, since today the state operates an advanced biometric identification system (Aadhaar) which is necessary for receiving welfare and other government services and is also used as a means of registering for services in banks, schools or insurance companies.

The data protection in the version of the previous law is also not valid regarding personal information available to the public, so that external companies can allegedly scrape the data from social networks and process it. This is what Clearview AI did, according to estimates, scraping 30 million photos from Facebook for its facial recognition system, which it later sold to law enforcement agencies in the United States.

The digital rights protection group, Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), in New Delhi, stated that the law does not include "some of the significant recommendations" received during the consultation process of the latest draft, "does not sufficiently protect the right to privacy", and should not be passed.

In the State of Israel, for comparison, there is no proper progressive legislation regarding the privacy of citizens in the digital age. The current law, which was written in 1981 and has not been amended or updated since the invention of the smartphone, does not really address the challenges that exist today. And yet, many Israeli companies operating in India, for example in the operation of large service centers, will have to go through a quick adjustment procedure in order to comply with the rules. For some, this is a continuation of the procedure they went through following the privacy legislation in Europe in 2017. Thus, Israel, which seeks to lead in the data-based artificial intelligence revolution, does not offer proper protection for its residents, but Israeli companies are forced to offer advanced protection to the residents of the European Union, and now also in India.