Breaking electrolysis: Inside the Israeli startup betting on cheap green hydrogen

H2Pro believes it can slash costs and clean up one of the world’s dirtiest industries.

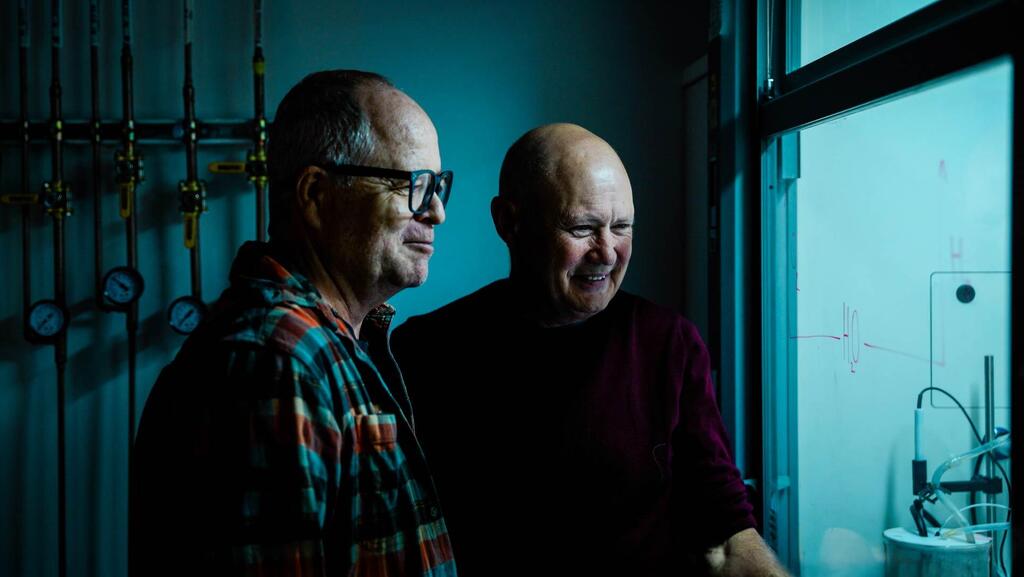

In the Caesarea industrial zone, an Israeli startup is working on a technology that could help reinvent one of the world’s most polluting industries. H2Pro, founded in 2019 after a chance bus ride conversation between two Technion professors and later led by serial entrepreneur Talmon Marco, is aiming to transform how green hydrogen, hydrogen produced without carbon emissions from renewable energy, is generated.

The means: a fundamental re-architecture of electrolysis, the decades-old process used to produce hydrogen from water. The ambition is bold, streamlining the process enough to drive the cost of green hydrogen down to around one dollar per kilogram, making it competitive with hydrogen produced using fossil fuels.

Today, the world consumes roughly 100 million tons of hydrogen each year, a market worth an estimated $200 billion. “The large hydrogen market today is in refineries, chemical plants, and steel manufacturing, and in the future, jet fuel production,” says H2Pro CEO Tzahi Rodrig. The problem is that hydrogen production accounts for roughly 2.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

“About half of the hydrogen used globally goes to ammonia production, and the other half to the oil industry,” says Prof. Gideon Grader, one of H2Pro’s founders from the Technion. “This market creates enormous pollution because of the way hydrogen is produced.”

Most hydrogen today is made using steam methane reforming (SMR), a cheap but highly polluting process that relies on natural gas. The clean alternative, electrolysis, which separates hydrogen from oxygen in water using electricity, has been known for more than a century, but it remains prohibitively expensive.

“The cost of producing hydrogen through electrolysis simply can’t compete with the polluting methods,” says Prof. Avner Rothschild, another Technion professor and company co-founder. The most expensive and problematic component, he explains, is the membrane at the heart of the electrolyzer, which separates hydrogen and oxygen gases.

“A membrane is a component that operates under constant stress,” says Rodrig. “Over time, it degrades. If it fails, hydrogen and oxygen can mix, and that’s an explosion risk.”

That insight led to H2Pro’s central idea: removing the membrane altogether.

“Our invention challenged something that no one had questioned before,” says Rothschild. Instead of producing hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously, separated by a membrane, H2Pro’s system generates the two gases in separate stages.

In the first stage, one electrode produces hydrogen while the other temporarily stores oxygen. In the second stage, the oxygen is released. “This two-step architecture dramatically reduces costs and complexity,” Rothschild says.

The change required an entirely new type of electrode. “We had to reinvent the electrode, its composition, its structure, everything,” he explains. At H2Pro’s R&D facility in Caesarea, engineers manufacture electrodes from scratch, mixing metal powders and sintering them at temperatures of up to 1,200 degrees Celsius to withstand the harsh operating conditions inside the electrolyzer.

Protecting the technology poses its own challenge. “You can’t protect hydrogen itself, it’s a natural molecule,” says Dr. Revital Green of the Ehrlich Intellectual Property Group. “Once hydrogen is sold, there’s no way to trace its origin. That’s why protection has to focus on the system: the components, their configuration, and how they interact.”

For hydrogen to be truly green, it must be produced using renewable electricity from solar or wind. But those energy sources are inherently volatile.

“Conventional electrolyzers don’t cope well with fluctuations in power supply,” says Rothschild. “They degrade quickly, and that comes at a high cost.”

H2Pro’s system, by contrast, can be turned on and off repeatedly without damage. “Existing electrolyzers can’t handle constant cycling,” says Rodrig. “Ours can.”

That capability allows the system to be connected directly to solar fields. In theory, farmers growing tomatoes or cucumbers could also produce hydrogen on-site and sell it as an additional revenue stream.

“To reach one dollar per kilogram of hydrogen, every cost component has to be attacked,” says Rodrig. “Electricity is the biggest one. At around five cents per kilowatt-hour, the math starts to work.”

Talmon Marco, who chairs the company after selling Viber for $900 million in 2014 and Juno for $200 million in 2017, is cautious about timelines. “A dollar per kilogram is an extremely tough target,” he says. “But reaching a low, economically viable price, probably around 2031, is realistic.”

Marco frames the effort as part of a broader climate solution. “Green energy may be less fashionable right now, but progress is real, especially in China,” he says. “In the end, we’ll have to go where the problem leads us: solving the climate crisis.”

H2Pro has raised more than $100 million from investors, including Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy fund and Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund. A 50-kilowatt system is already operating at its Caesarea facility. In February 2026, a 500-kilowatt system is scheduled to go live in Ziporit, near the Sea of Galilee, followed by a much larger system, up to 50 megawatts, in Spain or Portugal.

“There simply isn’t enough green hydrogen today,” says Rodrig. “Even if everyone wanted to switch tomorrow, the supply doesn’t exist. Someone has to build the infrastructure.”

That demand could soon explode. “Aviation wants hydrogen. Shipping wants hydrogen. Heavy-duty trucking wants hydrogen,” he says. “We’re talking about a market that could eventually reach trillions of dollars.”