"Without a long-term UAV program, Israel will not be maintained as a world leader"

Alon Unger, Founder and Chairman of UVID, one of the world’s largest conferences focused on the unmanned aerial sector, warns that despite the strength and scale of Israel’s UAV industry, it lacks the national support needed to remain competitive.

“UAVs are a national growth engine, and it should have a program that is budgeted and planned for the next short, medium and long term,” says Alon Unger, Founder and Chairman of UVID, in order “to maintain Israel as one of the five leaders in the world.”

“It’s more than 300 companies in Israel… it’s a huge economic issue,” he says. “In the year 2022… UAVs were 25% of the total defense export in Israel.

“It’s the most manned ecosystem that I know,” adds Unger.

Speaking to CTech, Unger argues that while Israel’s UAV sector is undeniably robust and globally influential, operating without a national program or cohesive long-term strategy, as well as under stifling regulations, means it risks losing the stronghold it has attained.

Despite accounting for a significant share of Israel’s defense exports in recent years, he says the unmanned sector is still not receiving the coordinated policy attention it needs as a national growth engine, stunting the full realization of its potential for the country. Given that Startup Nation holds national programs for space, cyber, and AI, he questions why its unmanned industry is not afforded the same status in its export priorities.

While Unger grants that in Israel “the ecosystem is very mature with this work,” he states “the cheese is moved,” and it is time for its governing and regulatory bodies to “wake up” to the fact that a leadership paradox has emerged. Despite Israel being instrumental in defining modern UAV capabilities, he argues it is not building the infrastructure required to sustain that position in the way other countries are doing.

“Many nations are looking at this as something that is a national strategy,” says Unger. “Building infrastructures, investing a lot of money in civil success, academic parts, technology hubs… opening the burdens of laws or restrictions.” He continues: “You can find a national program in the States… you can find it in Turkey, you can find it in Iran, in China, in India.”

In Israel, “it’s not this way,” says Unger. “The Education Ministry… doesn’t think this way yet.” By contrast, he says, Israel lacks a dedicated UAV airport or test range, as well as academic degrees specifically for UAV engineering. Nor does it have a national R&D budget for its unmanned sector, defense or civil, or any other policies that would cement the industry as a driver within Israel’s national economic planning.

The consequences of not treating the unmanned sector with the same gravitas as our global competitors, “investing in this technology, while the world is investing in this, and while the world is looking at this as a national issue,” says Unger, means “probably we will not be maintained as a world leader.”

Unger himself has spent 35 years embedded in Israel’s UAV ecosystem, first as a senior operator in the Air Force, then in industry, and later establishing the country’s main annual UAV conference after years of attending similar forums abroad. The idea emerged as he felt that “it doesn't make sense that the Israeli [UAV] community has to fly outside of the state in order to meet each other.”

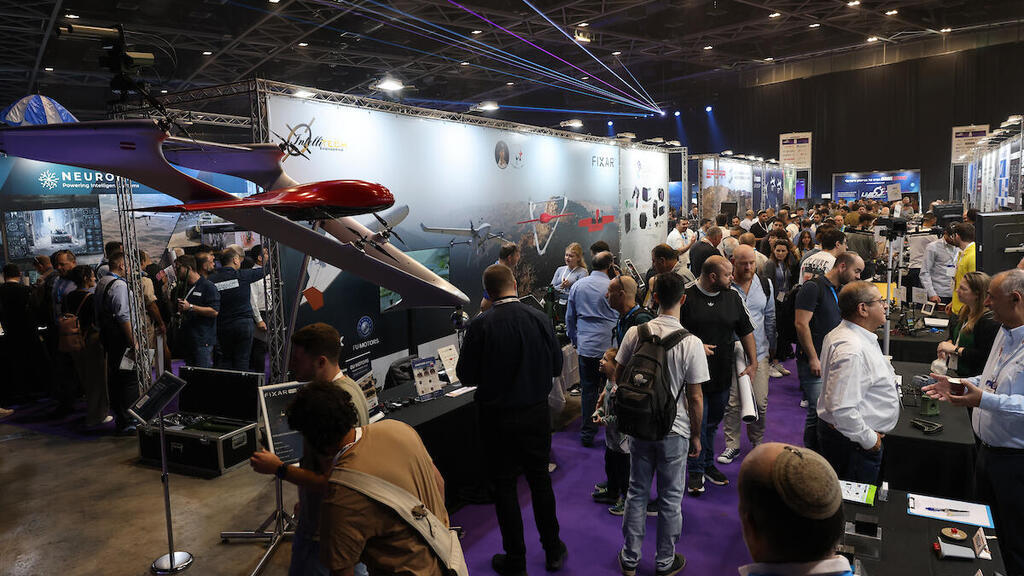

UVID started in 2012 as a convening platform, bringing together the sector’s defense contractors, startups, regulators, academics and international delegations. The conference held its latest gathering on November 26 in Tel Aviv and, according to Unger, was the second largest of its kind in the world.

One of Unger’s main concerns for Israel’s UAV industry is that beyond its military uses, the civil and dual-use segments (those used for both military and civilian purposes and the fastest-growing areas of the global UAV market) are underfunded and constrained. For the latter, he explains, these companies are often classified as defense exporters, placing them under the MTCR (Missile Technology Control Regime) and Israel’s own strict export licensing system.

Meanwhile, Unger contrasts this with the United States, where the Trump administration made adjustments to MTCR export rules specifically to support American UAV producers. “He was making kind of adjustments to support his economy and support the larger industries,” Unger says.

One of the consequences is that it places particular strain on funding, especially for venture capital. “There are capitals that are not coming here or not investing because it’s a large burden,” Unger says. He notes that countries less bound by MTCR and similar export rules are able to push more aggressively into the medium-altitude, long-endurance (MALE) UAV market, which was once dominated by Israel and the United States. “Today, there are something like 10 countries… selling the MALE system,” says Unger.

However, for Unger, the commitment to fortifying Israel’s UAV ecosystem is not only based on a reverence for its decades-long heritage but also on “looking at the future.” He calls the UAV community “the soul tree,” comprised of “many people that are working together in the last 50 years… and they wish it to continue.”

Yet even a community as wide-reaching as UVID has limits, and no conference can substitute the inertia that comes from the kind of higher-level national support he is lobbying for. “It’s one of the largest technology aviation markets in the world,” he says. “The challenges are… how to maintain your position… how to build strong roots which are relevant for our days today.

“It’s a duty of this community to be together,” he says. “We are here to continue.”