ISRAEL AT WAR

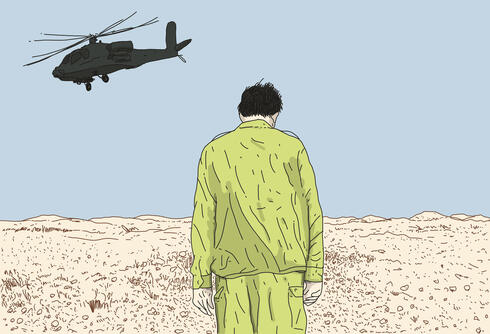

Amidst battle fatigue, Israeli soldiers find relief in unique resilience-building dialogues

Moments after they've left Gaza and moments before they return to it, IDF soldiers engage in group discussions with therapists, talking about their fears, guilt, and lack of motivation, reconnecting with their friends and commanders, and learning to find strength to continue. The members of the association who accompany them describe the complex coping mechanisms in the field, as well as those of the parents and partners who participate in wartime support groups

At the beginning of this meeting, these soldiers, who had just come out of Gaza a few hours ago, are hesitant. They don't know if what they are experiencing - extreme fatigue, loss of appetite, tension - is normal, or if it indicates post-traumatic stress. They are worried that their teammates or commanders are angry or disappointed with their performance. They don't know if they are also afraid. So, in the first stage, they start by breathing. "Many times, we start with breathing and grounding," explains the facilitator, Danny Neuman.

"Grounding" is a technique that helps restore a sense of security and maintain a connection with the here and now through short technical questions. After the initial calming, the stories start to flow. One soldier talks about the sharp smell of death that has been with him since the Black Saturday, another about the harsh sights he has been exposed to, and a third dares to start talking about fear. And suddenly, everyone realizes that everyone is afraid, including their commander. Someone shares a deep sense of guilt for not being able to save his comrade, and hears from the commanders or medical personnel that he couldn't have saved him, that he couldn't have done anything differently. Some cry, many embrace, sometimes they even laugh, and in the end, they even remember why they are there and what they are doing there. And then the soldiers, according to Neuman, "tell us: 'What energy you gave us,' they gear up and go back into Gaza."

Dozens of such meetings, involving hundreds of soldiers, have taken place since the beginning of the war. An hour and a half of conversation - not therapy, everyone emphasizes that - that allows soldiers and reservists in the south and north to release their emotions and receive validation for their legitimacy, to organize their experiences in a healthier way, and to gather strength, or as it is commonly referred to today, "strengthen their resilience." The meetings are led by members of the "For Tomorrow" Association; before the war, the association's members, therapists and group facilitators, conducted nature trips for discharged soldiers and reservists to help them cope with events they experienced during their service. Since the beginning of the war, they have accompanied soldiers in current operations, in cooperation with the army and the police. 25 volunteers from "For Tomorrow" work in the field as civilians, another five are already being recruited as commanders and engage in similar activities on bases, and there are also those who accompany the partners and parents of soldiers.

The power of these meetings in the field lies primarily in sharing. "Soldiers in combat, their fear response is natural and healthy, and some of them have lost friends, or they were there on October 7th and didn't have time to digest it," explains Dr. Shai Shorer, a clinical social worker and researcher at the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Haifa, who has led ten meetings since the beginning of the war (and serves as the research center of the association). "These conversations give them an opportunity to share with friends and hear from friends. They tell us, 'We haven't talked about it like this until today, we were busy with action, but now that we can talk about it and not be afraid to talk about it, and our teammates can hear me and give a normal response to the pain I express - then we can move forward.'"

This is a point that everyone emphasizes: it is not just a matter of "venting". The initial emotional response provided by these meetings is also a significant need for the continuation of activity. "Today there is an understanding that if there is a psychological response, the soldiers' functioning will be better," explains Guy Zimerman, a social worker and psychotherapist who has been recruited to the reserves as a captain since Black Saturday. "The commanders and soldiers understand this, and even at home - there are women who asked their combatant partners that when they return from operations, they should go to the captain. I made it clear to our commanders that no one leaves home before they meet with me. It is necessary."

"Each person needs to talk about things that help them cope," explains Neuman, who specializes in leadership development and is a trained psychologist and group facilitator who has already led seven meetings in the gathering areas in the south. And then he starts to elaborate. "Combat responses can include sleep problems, anxiety, emotional detachment, and basically what we say is 'it's normal, everything is normal at this time, these are normal responses to an abnormal situation,' and of course, if we identify something abnormal, we refer them for treatment. So when fear arises, we say 'it's normal to be afraid,' we don't say 'be brave.' To be afraid is also to show responsibility. Even your commander is sitting here and saying he is afraid, it's okay."

This is really the first aid.

"Yes, we don't do deep processing, and we even avoid it, so we don't ask 'how are you?' but rather 'how was your day?' to connect to action and proactivity and not to expectations. We also don't go into graphic descriptions. At this stage, in order for them to be there at the peak of alertness and capability, we need to avoid emotional expectations. But when things come up, we don't say 'we won't talk about it now.' We simply don't want to go too deep, we leave it at a level where you can express your feelings but we don't treat it now."

"And the emotions, as expected, come up. In one of the meetings, a soldier talked about an event inside Gaza, where one of his team members was injured and killed," Neuman recalls. "The soldier blamed himself for not reaching him in time, he said, 'If I had arrived five minutes earlier or even a minute earlier...'. In the meeting we had after the event, the team doctor told him, 'Even if it had happened on an operating table, he would still have died'. When this soldier heard that, and received such a timely team hug, it was very helpful. It was incredibly moving."

This is also part of the process of reframing the story, "so that they don't have a narrative of helplessness or despair, but rather one of proactivity, a desire to protect. If there is a narrative of 'I am ashamed of an army that failed to protect the settlements,' we try to replace it with 'I am a soldier, and I am willing to sacrifice my life for the homeland.'"

And from here, they move on to the central theme of "resilience resources". "We tell them - look at where you draw your strength from, so that they don't connect to despair, depression, and anxiety, but rather to capability. We ask 'what enables you to cope?' and they answer - 'seeing my officer and receiving personal example from him', 'being with my entire team', 'protecting my family', and then one breaks down in tears. It connects them to their own abilities, each one with themselves, and when the whole group hears these answers, it does something to the diversity of their resilience resources. It reminds them that their activity has a purpose, a meaning. And the fact that they have been exposed to personal stories of the victims, that these are families, children - it engraves a strong memory in them, and on one hand, it is complex for coping, and on the other hand, it gives them a lot of strength and resources to fight. The motivation is very strong."

Neuman demonstrates how such a change in narrative can look, even in the case of a soldier who managed to do it on his own: "Someone told us that he entered one of the communities in the Gaza periphery during a battle and constantly felt hunted, until he saw a woman fleeing from her house and a terrorist shooting five bullets into her back, killing her. At that moment, and he really remembers it, he said to himself, 'From now on, I am not the hunted, I am the hunter'."

How to trust friends, how to talk to family. The conversations, as their facilitators testify, can change the soldiers' functioning in the field, and also afterwards, at home. Zimerman, for example, says that they also give soldiers concrete advice on how to cope with difficulties falling asleep or with a sense of helplessness and recurring thoughts about the events. "These things are more effective during waiting times, not when fighting in the field, and one way to deal with them is to create a clear daily routine, knowing when to wake up and what to do throughout the day, and it is also recommended to do sports. Before going to sleep, if there are difficulties falling asleep, it is advisable to do a review ceremony of the entire day, and then 'close' it, literally saying, 'Okay, now I put things aside and focus on sleep, and I will come back to the things that occupy me tomorrow.' Breathing exercises are also an effective tool before sleep to create less threatening thoughts, an alternative to difficult thoughts."

Another tool given to soldiers in these meetings is the Yehalom model for initial treatment of a severe emotional response (acronym for establishing contact, emphasizing commitment, clarifying facts, verifying the sequence of events, giving tasks). "This is actually the first aid they can do in the field in case of a crisis response," explains Zimerman. "The goal is to help the affected soldier regain a sense of capability, as it will reduce the risk of post-trauma. First and foremost, we establish a connection with them - some kind of connection, each one at their own level. There may be those who won't listen to us because of the situation or because they are absorbed in themselves, but maybe a touch will allow them to be with us, for example. We emphasize to them that they are not alone, that we are with them, we remind them who we are, and we ask them short and focused questions to organize the story around the event - who was with you, who was the commander.

3 View gallery

IDF Chief of the General Staff Herzi Halevi talks with soldiers in the Gaza strip.

(Photo: IDF)

Who is with you, who is your commander, it grounds them, and we tell a story that will help build the narrative, 'we are in such and such a place, they are shooting at us, we need you to return fire, you are protected and capable of shooting'.

The idea is to get the soldier back into activity, and if they are unable to shoot, they are given another task so that they don't feel useless. When we succeed in doing this, the likelihood of feeling guilt or inadequacy is reduced. The Yehalom model is focused and very helpful, and anyone can do it, so we explain it to the soldiers in our meetings with them.

Another source of power that the meetings greatly strengthen is group connection. "These soldiers are themselves serious resilience experts, and we simply encourage them to take a moment to think about it, talk about it, bring examples of their coping abilities, and through such collaborations - because these are not conversations that happen among reservists - an atmosphere of security and trust is created among them, and these are serious resilience resources," says Shorer. The definition of resilience is the ability of any entity, whether it be a person, a team, a platoon, or the entire society, to absorb a blow, cope with it, recover, and grow. And we see this in small and big moments. So if they leave the workshop with a feeling that they can rely more on their comrades, not only in combat but also in all aspects related to its consequences, it has significant value.

The change, he says, is felt already during the meetings. "Suddenly there is laughter, suddenly there is an atmosphere of sharing, of inclusion, and it is so different from the stress and trauma they have experienced, it balances them, we see it. And they take it with them, we have seen it in the activities of the association in the past. People have told us, 'Until I participated in the activities, I couldn't talk about it with anyone close to me. Now, after practicing these things, I can talk to them more fully.' This is also a resource, and also using it, the possibility of relying on support systems around, is critical to reduce distress and minimize trauma over time. So if the soldiers are less afraid of emotional conversation, if we help them to seek and also provide help, that is also very meaningful."

Clinical psychologist Doron Merom, the professional director of Bishvil HaMachar, also emphasizes the need for strengthening resilience, rather than psychological treatment as done in other frameworks. "There is a tendency for mental health professionals to talk about how you feel and what it did to you, and that is something that should not be done at this stage of combat. We need to focus on resilience and work in a focused manner, what helped you." Merom, like the other interviewees, praises the collaboration with the army and the police, and notes how important it is to connect soldiers with members of the association they already know, "so that it won't be something sporadic but rather a therapeutic sequence," even if it is not technically therapy.

Parents and partners at home have already opened a "Place for Concern." In addition to meetings with the soldiers, Bishvil HaMachar Association also provides a response in war to partners, couples, and parents of the soldiers, and operates about 70 Zoom groups, with about 600 participants. If you will, you can call it a place for concern. "What arises in these groups is primarily existential concern," says Dr. Meitari Shacham, a clinical social worker and head of the second-degree program in movement therapy at the Kibbutz Seminar, who leads the association's journeys and now accompanies groups of partners.

Naturally, what arises in the groups of parents is different from what arises in the groups of partners. For women and partners, for example, existential concern is not only about concern for their serving partners but also about the overall picture of the war: "There was a feeling that home is not a safe place, so they returned to their parents' home, they are distant from friends, some of them are not working, or wondering when to return to work because maybe if I go back to work it means everything is okay and I am abandoning my partner who is currently at war and not working, maybe I should also take a break. There are questions of 'forbidden pleasure', if they have permission to enjoy. And of course, there is a lot of loneliness."

Even when the partner returns on vacation, it becomes clear that the difficulty does not disappear. "There is a great expectation that he will come, and everything will be fine, but the reality is different. He settles back into life, she releases a lot of pressure, so sometimes there are arguments, and sometimes until they manage to move on from the arguments and enjoy a little, he goes back to the army and the partners are left again with emptiness and anxiety." Partner groups allow them to share experiences and receive support and even more concrete advice on how to navigate communication or meetings, and they also encourage them "to find other outlets for their needs - a friend, a cousin, a colleague at work whose partner is also in the military."

The coping strategies of parents, as mentioned, are different. "The questions that arise are how do I get through this, how do I breathe, how do I sleep, how do I deal with anxiety, and here we leave it at the level of ventilation - we let them talk, and we give tips to strengthen," says Tal Baruch, a psychotherapist and group facilitator, who led journeys for Bishvil HaMachar and now accompanies parent groups. "And there is another issue. Everyone puts the needs of the child first, and then the questions arise: when the child - because he is always a child, even if he is already nearing release from service - contacts from the field, from the combat, how should we interact with him, what do I say, what do I ask, they really seek some kind of guidance. And what happens when he returns, after or when the war is over?".

The concern for the soldiers' well-being arises again and again, and here normalization is also important. "One of the things we keep telling parents, as well as fighters and partners, is that the physical and emotional reactions you experience yourselves or see in your children are normal reactions to abnormal events," emphasizes Baruch. "This is a very important sentence that brings a lot of order and calm. What you are seeing now is what happens in the first few days and weeks after the event. It does not mean that your child will be post-traumatic. 90% will heal. If these reactions persist for several months, then it will be time to consider treatment, but most likely what you are seeing now will pass, and it is important not to panic, to understand that it is a natural process. We guide them on how to ask questions, not to dig and not to press, because it is not appropriate to open everything right now, it will come later. Don't overprotect, don't smother, it is not appropriate at the moment, but if the child needs to open up and talk, then convey that you are strong enough to listen."