"This is no longer just a crack in Nvidia’s hegemony, but an entire pipeline, and we intend to expand it"

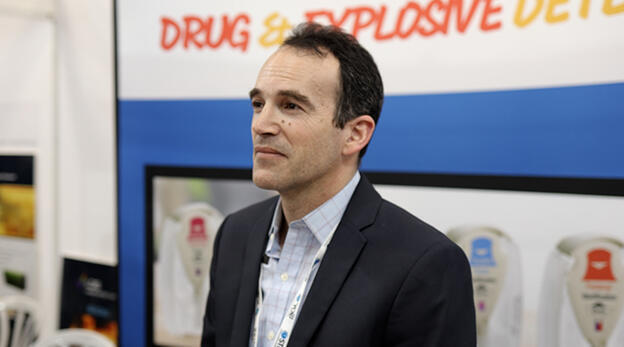

Ofer Shacham, former Head of Silicon at Meta and a key leader at Google's silicon, co-founded Majestic Labs to develop energy-efficient AI processors capable of challenging Nvidia’s dominance.

On a winter day in 2018, Sergey Brin, one of Google’s co-founders, invited Ofer Shacham for a personal conversation. When the two sat down, Brin opened a new file and asked Shacham, then Head of Silicon Design and Implementation, Consumer Hardware, a simple question: “Write down the next thing you want to do at Google, and we’ll start running it.”

The number of times people receive offers of this kind, in any industry, can usually be counted on one finger or less, but the then 40-year-old Israeli engineer had to refuse. Just 10 kilometers from Google’s headquarters, an even more tempting offer awaited him, extended by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. “Google tried hard to keep me, and I had an open ticket from Sergey, but what awaited me at Facebook at that time was a crazy engineering challenge, setting up the company’s AR (augmented reality) silicon activity,” he says.

What was so challenging about it?

“This meant taking hardware that exists in server farms and cramming it into smart glasses without the battery inside the glasses overheating and burning the user’s ears,” explains Shacham (48), now co-founder and CEO of the startup Majestic Labs, in a first and exclusive interview with Calcalist. “All that Mark told me and the team recruited by Facebook as our mission statement was: ‘All-day wearable, socially acceptable.’ This sounds concise and simple on the surface, but in practice it is almost impossible to implement, because the smart glasses he envisioned also had to look good, be suitable not only for geeks, and be lightweight. Regular glasses weigh about 40 grams, so glasses that weigh more than 80 grams are too heavy. As a result, during the development process, every gram in the battery or chip had to be carefully considered. In the five years I worked on the project, I built a team of more than a thousand people from scratch, and with budgets of hundreds of millions of dollars, we developed 15 chips for this project.”

Presumably, one of the reasons Zuckerberg’s smart glasses did not become a hit is that his definition of “socially acceptable” differs from that of the average person. Still, Shacham’s team, where he served as Vice President, Head of Silicon, met the technological mission it was given and brought Facebook into the field of chips needed to run artificial intelligence applications. Shacham led the silicon team expansion in Israel. About a year after his departure, the operation was shut down and most of its employees were laid off.

"Sergey and Mark didn’t get where they are by chance"

Shacham, a man without the ego-driven mannerisms that characterize many entrepreneurs, has accumulated quite a few Brin hours and Zuckerberg hours over the course of his career. And as happened at Google, even after he moved to Facebook (now Meta), Zuckerberg tried to keep Shacham at the company every time he considered leaving. Among other things, when Shacham and his family decided to return to Israel after the coronavirus pandemic subsided, Facebook allowed his role to move to Israel with him. It was that important to Zuckerberg to retain the humble Israeli engineer rather than look for a replacement in Silicon Valley.

Do you enjoy working with Zuckerberg? He’s considered a difficult person.

“I know it’s going to sound like a cliché, but Mark is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. He can walk into a conference room in flip-flops and a T-shirt, go over to an engineer and talk about code as if he were one of the junior programmers himself, and then sit down at the executive table with ten other VPs, of whom I was one, and ask a really smart question about a footnote on page 13 of a document that he’s probably one of the only people who read in full in advance.”

Who is more impressive: Zuckerberg or Brin?

“Sergey probably has higher emotional intelligence than Zuckerberg. The first time I met him at Google was when I was sitting at lunch in the cafeteria and he just walked up to me without knowing me, asked if he could sit next to me, and then inquired a bit about what I do. What I can say about both of them is that they are very impressive people who didn’t get where they got by chance.”

Two of the world’s top industry executives are courting you, and yet you decided to return to Israel.

“During the pandemic, we were in isolation for 364 days, and at one point my wife told me: ‘Enough, it’s time to go back.’”

The Shacham family, with its three children, all born in Palo Alto, settled in Hod Hasharon, the city where he and his wife grew up, and had to adjust to the new environment in the midst of war. “It takes some time to get used to the intensity and aggressiveness of Israel, especially for the three children who were born in the United States and were therefore new immigrants in every sense of the word,” says Shacham. “The differences are in the small things in daily life. The children were mostly shocked by the noise in the classrooms when they entered them in the morning, and by the students’ attitude toward the teachers. But in the end, the Israeli roughness is actually good preparation for life.”

And how did you feel during the transition?

“Facebook informed me that the position would move with me to Israel, but after a period of work that started at 4 p.m. and ended at 2-3 a.m., I felt exhausted. In the background, I also saw what was beginning to happen in the field of AI and realized that I had to act.”

The next chapter in Shacham’s career sounds like the beginning of a joke: an Israeli, an Iranian, and a Japanese woman decided to establish a startup to develop processing chips tailored to the massive computational demands of artificial intelligence, without consuming electricity on a country-wide scale. During 2023, Shacham, Sha Rabii, and Masumi Reynders, who had worked with him in senior positions at Meta, resigned from the company, and in August they began working together on their ambitious project, designed to challenge Nvidia’s hegemony in AI processors.

You didn’t set out on this new path with perfect timing.

“We officially launched Majestic Labs AI in November 2023, already in the midst of the war in Israel. We raised $100 million in two almost consecutive rounds that were in high demand, and we could have raised double that.”

Didn’t the partners ask you to return to Silicon Valley in light of the war raging here?

“The partners didn’t say anything. We’ve been working together for 15 years and they’re like family to me, but other people kept asking questions. There were venture capital funds that explicitly made their investment conditional on my moving to Palo Alto, and that’s why I didn’t take money from them. Beyond that, it was important for me to have Israeli funds on the board so I would have support for staying here,” says Shacham, explaining the combination of Israeli funds Grove Ventures, managed by Dov Moran, Lior Handelsman, and Renana Ashkenazi, Hetz Ventures, Tal Ventures and QP Ventures. The first round was led by one of the hottest funds in the United States today, Lux Capital, which specializes in hardware and defense investments. The second was led by the relatively new Bow Wave Capital fund, managed by former Israeli Itai Lemberger.

Today, Majestic is registered in the United States, but Shacham is far from the only Israeli working for it from Israel: about half of the company’s employees live here. Rabii, Shacham’s Iranian partner and the company’s president, can relate to the issue of homesickness. He was born in Iran and came with his family to the United States as a child on the eve of the revolution. When the Shah’s regime fell, they decided not to return.

Was it difficult to run the company together during two years of war here, including tensions with Iran?

“There are the countries of Israel and Iran, which have complex relations, and there are the people who live in them. In the United States, I worked with many employees of Iranian origin, and we also have investors of Iranian origin in the company. When missiles started falling from Iran, they were the first to contact me, by any means of communication. I received dozens of messages from them, and I also asked how their families were doing, because it wasn’t easy in Tehran during that period either. Ultimately, these are relations between people who want to live in peace. Iranians are very similar to Israelis: they take great pride in their cultural heritage, and it’s clear that the vast majority don’t like the regime.”

So you’ve founded a company and you’re serious and ambitious people, but let’s be realistic: the idea that a small Israeli startup will defeat Nvidia’s hegemony and compete head-to-head with it isn’t crazy to you?

“‘Win’ is a big word for a small startup facing trillion-dollar companies that built the chip sector. Even with the word ‘compete,’ I’m cautious, because Nvidia currently controls about 90% of the market, so any activity in the processor space inevitably competes with it. That said, we identify areas where Majestic has an order-of-magnitude advantage over Nvidia. We’re solving a problem that no one else has a solution for today, just as we did when we worked on chips at Google and later on the glasses at Meta. In AI, there is a once-in-a-century opportunity right now to build a company in the midst of a transformation that affects everything in the world.”

And you know the key figures in the field very well.

“We built a one-of-a-kind team, which currently numbers several dozen employees, because we had access to the best minds in Israel and Silicon Valley. Over the years in the United States, I’ve recruited about 1,500 engineers, so I know a lot of people in the field. Recently, Google did a great job breaking new ground with its TPU chips. This is no longer just a crack in Nvidia’s hegemony, but an entire pipeline, and we intend to expand it.”

"We thought it would be nice to see a little of the world"

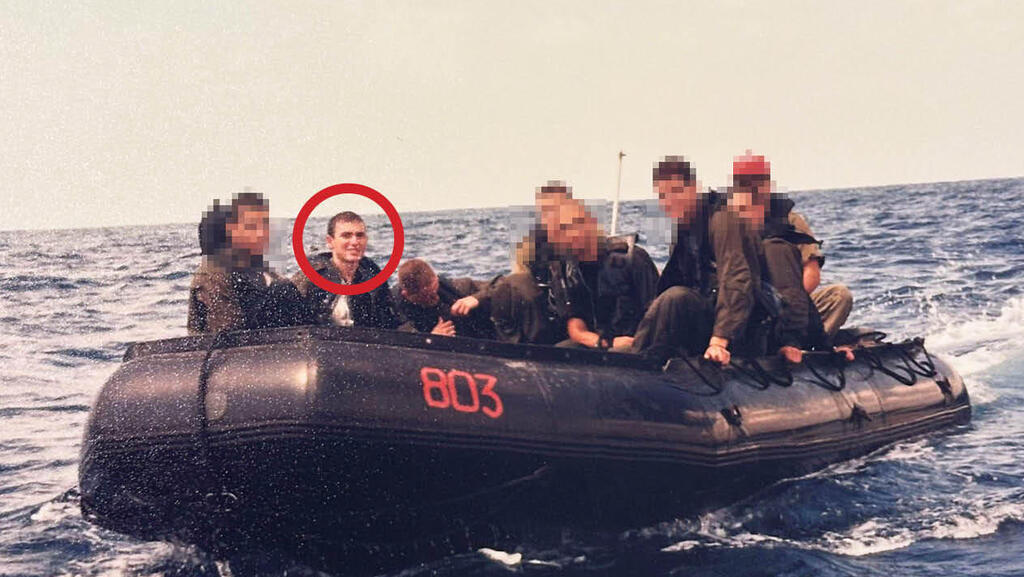

It is likely that if Shacham had read these words 25 years ago, he would have had difficulty imagining that the man at the center of the story could be himself. Unlike many entrepreneurs and executives in the Israeli high-tech scene, Shacham was not a computer geek, did not serve in a technological unit, and in fact came to his impressive career largely by accident. As a child, he dreamed of becoming a doctor, and while others were programming or playing computer games, he volunteered with MDA (Israel’s national emergency medical, disaster, ambulance, and blood bank service). His military service in the naval commando also did not bring him closer to his future career. “I can’t count to 8200, only to 13,” he jokes about himself.

After being discharged from the IDF, Shacham was close to enrolling in medical school, but at the last minute changed his mind. Seven years of study seemed like too long, so he decided to change direction and study electrical engineering and computer science at Tel Aviv University. He had no idea that, without any detailed planning for the future, this choice would set him on a 12-year path that ended with a doctorate at Stanford University.

Describe the state of mind you were in when you started your studies.

“I was so far from this world that in one of my first classes I went up to the professor and said, ‘I don’t even remember what a derivative is, what are you talking about?!’ That was my level. During my degree, I worked as a diving instructor, and only toward the end of my undergraduate studies did I start working at IBM and thinking about entrepreneurship. But I felt I didn’t know enough to invent something new. Around that time, I got married, and my wife and I thought it would be nice to see a little of the world and do a master’s degree abroad.”

Stanford is one of the world’s most respected universities in engineering and technology. That’s a bit more than “seeing the world.”

“It’s almost embarrassing to admit, but I only applied to universities whose names I recognized from movies and TV shows. My wife wanted us to live somewhere with nice weather, so the only university I applied to on the East Coast was MIT in Boston, because it’s the most famous institution. In the end, I was only accepted to Stanford, but the embarrassing part of the story doesn’t end there. During the application process, I consulted one of my undergraduate professors, and he told me, ‘If you apply only for a master’s degree, you have no chance of getting a scholarship. How are you going to pay for your studies? You have to apply for a doctorate first, and then you can decide what to do.’”

The young couple arrived in the United States, and Shacham, who did not receive a scholarship, had to find a job to support himself during his studies. By chance, he found a position very similar to the one he had held as a student at IBM in Israel, and became a research assistant in a Stanford laboratory working on chip-related projects. “The person who hired me was Professor Mark Horowitz, head of the faculty and responsible for the entire field of silicon chip design at Stanford,” Shacham says, describing one of the world’s leading scientists in the field and the founder of Rambus, a chip technology company traded on Wall Street with a market value of about $10 billion.

“After one quarter, I went up to him and said, ‘Listen, the project isn’t finished yet, should I look for another job, or do you want me for another quarter?’ He said, ‘Stay for another quarter.’ After another quarter, I asked again, ‘It’s still not finished, do you want me?’ And so, little by little, the first doctoral students I helped completed their degrees, and I inherited the project. I didn’t plan to pursue a doctorate, but that, too, happened by chance, because of Horowitz.”

How do you end up with a doctorate?

“At Stanford, there’s an admissions test for the transition to a doctorate. About 250 students take it each year, and around 80 with the highest scores are accepted. The test is a series of interviews conducted in a single day with ten professors in your field. Each one puts you in front of a blackboard and asks professional questions. I knew I didn’t want to do a doctorate, so I didn’t prepare at all. At the same time, I had to take the test so they wouldn’t know I wasn’t planning to continue. The plan worked perfectly: I ranked 82nd, which meant I wasn’t accepted. But then Horowitz said, ‘I know exactly how much you studied, and I don’t want you wasting your time taking this test again next year. I filed an appeal for you, and you were accepted.’”

"In the Stanford lab, I was in the right place at the right time"

Two decades ago, long before anyone predicted the massive computing needs that the then-nascent AI revolution would demand, few engineers understood that it would not be possible to keep shrinking silicon chips indefinitely, as Gordon Moore, one of Intel’s founders, had predicted. Shacham’s research group at Stanford, which included industry figures such as Bill Dally, who later became Nvidia’s chief scientist, and Kunle Olukotun, founder of the AI chip company SambaNova, was among the first in the world to challenge the doctrine known as "Moore’s Law." Their argument was simple: cramming more and more transistors onto ever-smaller chips and trying to run them fast would cause processors to overheat, or even catch fire. In other words, Shacham was at the forefront of designing processors for the AI era.

“It’s the kind of story of being in the right place at the right time. In 2010, I started working on a startup I founded, and the academic breakthrough in AI began in 2013. We started building processors for specific applications, the same direction Google is pursuing today with its AI processors, and also writing papers on the subject. That was the focus of my PhD. In 2011, Google, which had just established its first silicon group under the Android division, became my first customer, and a year and a half later it acquired my company.”

Why did you think such computing power would be needed in mobile phones?

“When I joined Google, I told people, ‘Computer vision and artificial intelligence are going to be the next thing in smartphones.’”

And they took you seriously, even though it sounded far-fetched at the time?

“That’s right. At Google at that time, they reacted to almost every crazy idea with: ‘Wow, that’s cool. Let’s see what we can do with it. Get some people and prove it’s feasible.’ That’s how we built the world’s first AI processor, which was later launched on phones.”

And so Google’s TPU processor came into being, designed to accelerate certain applications?

“The work on TPU, a processor dedicated to AI tasks and now competing with Nvidia’s processors, was in a different group, but I helped found it in 2013 and worked closely with those leading its architecture. They built a processor optimized for data centers, and we built one suitable for phones. In 2018, just weeks apart, Facebook approached Rabii and me, and we both moved there to establish their Silicon Group.”

“In a market worth trillions annually, it’s still worth investing for investors”

Today, the three former employees are focused on developing chips specifically for AI, unlike the graphics-focused chips that Nvidia continues to use. Nvidia, founded by Jensen Huang, began as a supplier of gaming GPUs and is now valued at $4.45 trillion. Around 2019, when Nvidia acquired Israel’s Mellanox, Huang realized that gaming hardware could also handle the massive data demands of AI applications. But as AI scales, server farms loaded with Nvidia chips consume unprecedented amounts of energy, and electricity bills are soaring.

Against this backdrop, the industry recognizes the need for AI-dedicated chips that are energy-efficient and for new approaches to server farm load management. Recently, Google demonstrated that its TPU chips could compete with Nvidia’s offerings. Shacham, Rabii, and Reynders aim to challenge Nvidia from the other side: designing extremely efficient servers that reduce energy consumption and operating costs. The product is still in development, but Shacham says Majestic already has several customers involved in the design process.

Why would server farms choose your solution over Nvidia?

“Our server can be 10 to 50 times more efficient than existing solutions. It can serve as a cloud platform while providing fast, precise processing for clients in finance, pharmaceuticals, and other industries. It can replace an Nvidia AI server or complement it to solve tasks where Nvidia is less effective. I won’t tell customers to discard their current systems, but in the near future, data center capacity will double, and we want to be in all the new facilities being built. The AI computing market will reach hundreds of billions, possibly trillions, annually. It’s enormous, and no efficient solution exists yet.”

Shacham is correct, but Majestic isn’t the only startup trying to challenge Nvidia. Israeli startups run by Avigdor Willenz, an expert in the field, are raising capital quickly, as is the unicorn NextSilicon.

Doesn’t that competition add stress?

“Competition is healthy. It’s not really me versus Avigdor Willenz, it’s all of us against the giants of the market. If anything, collaboration is better; it allows us to move forward together. I’m glad I’m not alone, there are other brilliant minds around me.”

Aren’t you worried the AI bubble could burst, given your $100 million fundraising for a team that doesn’t yet have a product?

“We weren’t in a rush to raise capital. Each founder initially wrote a personal check, giving us a budget to quietly work on the business and technology plan. Investors noticed we left Meta to pursue a new project, and the inquiries never stopped. Even after two fundraisings, investors contact us daily.”

And yet, for now, you are selling a vision rather than a product.

“We are developing the product, but it will take time. Data center construction takes one to two years, and companies investing billions want the most efficient solutions. I’m not selling a server like Nvidia’s at a 20% discount. I’m selling a server that can serve ten times more customers on the same infrastructure. It’s a game-changer. The urgency is real, some European countries already block server farms due to electricity shortages.”

You are clearly invested in the ecosystem, but is there a bubble in AI?

“AI is already transforming every part of our lives and will continue at a breakneck pace. Not every company will survive, some will fail. Some growth in data centers is ‘healthy inefficiency,’ some is fear of missing out. But in a market worth hundreds of billions or trillions, investing is still worthwhile for investors.”

Most readers might assume you will eventually be acquired by Nvidia or its competitors.

“An employee once asked me: ‘Is the product really the product, or is the product the company?’ My answer: We’re building a product that will allow the company to grow, be profitable, create new products, and expand. That’s my objective function. We live in a world where all areas of life are changing - from art to medicine. And this happens once in a century."