The deepfake hustle: How AI is weaponizing the voices of trusted economists

Impersonation scams are flooding Instagram and Facebook, exploiting the reputations of real experts while platforms do little to intervene.

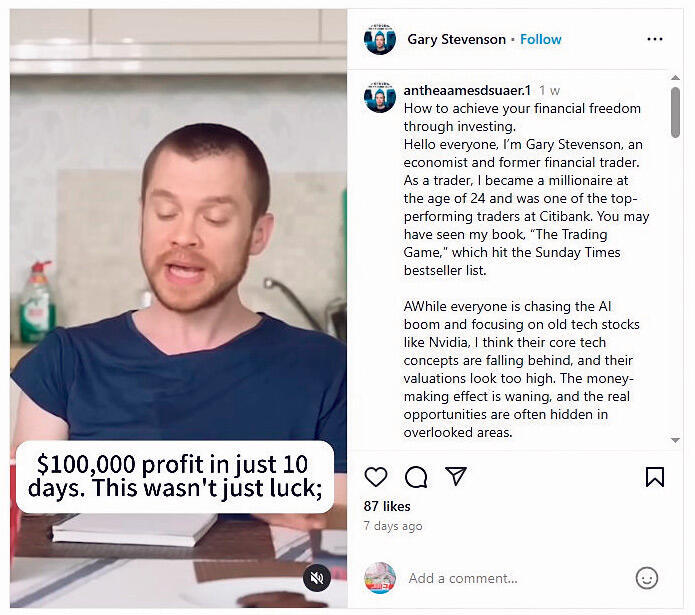

The Instagram video looks promising. Respected economist and author Gary Stevenson is seated behind what appears to be a desk in his home. On the desk are papers, a notebook, and a can of Coke. In the background: a sink, a kitchen cabinet, and a bottle of dish soap. Stevenson, dressed in a dark blue T-shirt, has a tempting offer: join an exclusive WhatsApp group where he shares hot stock tips.

“Last month, a recommendation of mine allowed one of our members to make an incredible profit of $100,000 in ten days. It wasn’t just luck—it was the power of strategic investing,” he says confidently.

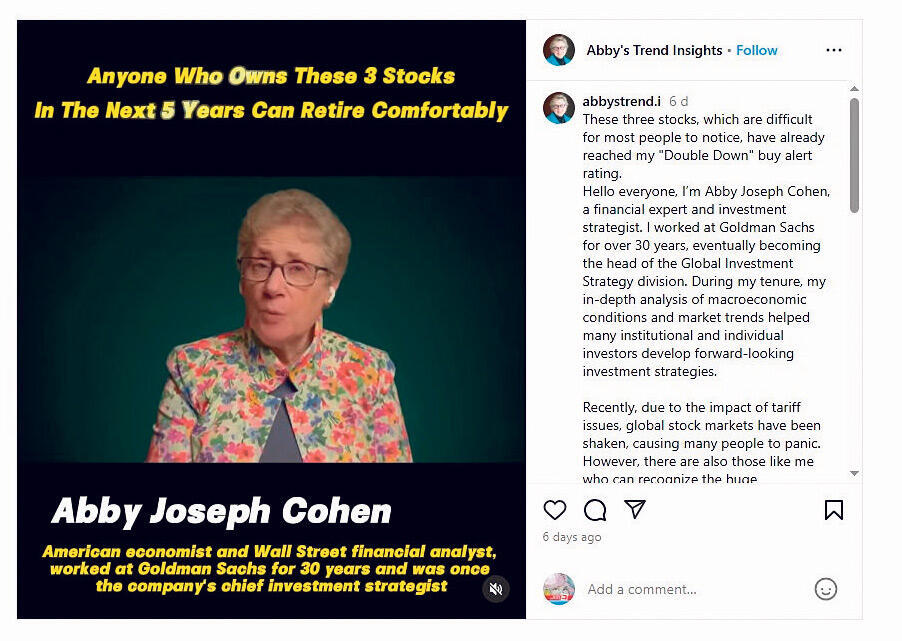

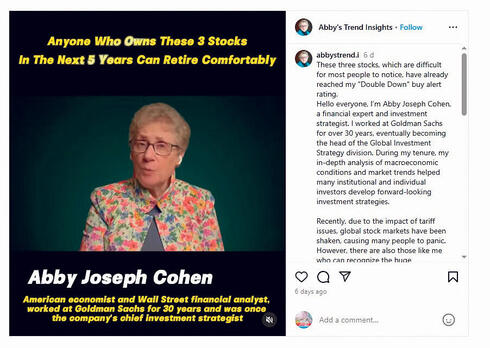

Similar videos circulate online featuring other high-profile economists. David Kostin, a senior strategist at Goldman Sachs, makes a similar pitch. So does Abby Joseph Cohen, a former Goldman Sachs executive and now a professor at Columbia Business School; Anthony Bolton, the legendary British investor who serves as the President of Investments at Fidelity International Limited and manager of Fidelity China Special Situations; and NYU business professor and popular commentator Scott Galloway. All of them appear to promise market-beating advice through WhatsApp groups.

The problem? Every one of them is fake. These videos are products of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) or other deepfake technologies designed to impersonate real people and trap unsuspecting users in scams.

Platforms turning a blind eye

What are platforms—especially Meta—doing to fight this? The short answer: the bare minimum. Despite many of these fakes being easily identifiable, they often remain live for days and are only removed after receiving major attention in traditional media or on large social media accounts.

“It’s crazy—they say everything is fine,” says Micha Catran, a financial content creator and the face behind the YouTube channel Micha Stokes, whose image has also been used by scammers. “I reported one account to Instagram and got a response saying it didn’t violate their rules. And it’s not the first time. These accounts are even promoted through paid ads—so clearly, they don’t care.”

A history of deception, supercharged by AI

Financial scams are nothing new. The earliest documented scam dates back to 300 BCE, when a Greek merchant insured a cargo ship, tried to sink the empty vessel, and collected the insurance payout while keeping the cargo.

In 1814, a conman impersonating a British army colonel falsely claimed that Napoleon had been defeated, triggering a rally in government securities on the London Stock Exchange. In 1880s America, Elizabeth Bigley posed as the daughter of Andrew Carnegie and defrauded banks of millions.

The internet gave these scams new tools. The infamous “Nigerian Prince” scam migrated from fax to email, and phishing attacks became widespread in the mid-1990s. But GenAI has taken things to another level. Since 2022, with the release of DALL·E 2 and ChatGPT, fraudsters have gained easy access to powerful tools that can generate hyper-realistic voice, video, and images with little oversight.

These tools are now being used to create fake videos of economists and investors. The results aren’t perfect—the voices are slightly off, movements are jerky, and gestures may glitch—but they’re convincing enough to deceive a percentage of viewers. With mass distribution, even a small success rate equals significant financial gain for scammers.

Scam playbook: Pump-and-dump, smart contract fraud, fake courses

These fake videos serve multiple types of scams. In pump-and-dump schemes, scammers buy illiquid stocks at low prices and then lure investors to buy in, creating a temporary price surge. They then sell at the top and vanish.

Another scam involves convincing victims to transfer money into supposedly “smart” investments. In reality, the scammers disappear with the funds. Catran has encountered yet another variety.

“Every now and then someone messages me: ‘When do I get the course link?’ And I ask, ‘What course?’ Then they say, ‘I just transferred money to you.’ One person thought he had sent me 30,000 shekels. I explained it wasn’t me—it was a scam.”

Many of these fraudulent videos are promoted through Meta’s ad platform. And platforms are often slow—or unwilling—to take them down.

“Broken trust”

Over the past week, Calcalist tracked several videos that automated systems should have flagged as AI-generated. Users also commented, flagging the videos as fake. Yet, they remained online for over a week, continuing to reach and mislead new users.

As a result, victims of impersonation are forced to constantly defend themselves.

“I pinned a video on both Instagram and TikTok warning people. Every few days I post a story. I spend my time warning people instead of Meta removing the videos,” Catran says. “These scammers use Meta’s ad platform, and that creates a conflict of interest. They get hundreds of reports and still do nothing.”

In responses from Meta, Catran was told the posts “do not violate community guidelines on impersonation and fraud.”

Ironically, Catran praises Elon Musk’s X (formerly Twitter) for its swift action.

“Every scam account I report there is removed within 24 hours. Every single one. They’re efficient. Meta is wasting everyone’s time.”

But the consequences go beyond inconvenience.

“When you’re constantly seen warning people about scams, some followers just unfollow you. They don’t want the risk,” Catran says. “It damages my reputation, my income, and my viewers. It’s a breach of trust. I keep refuting the lies so people know it’s happening. And yet, people still fall for it.”