"There will no longer be paperwork": The professor who wants to kill the PDF

Factify founder Matan Gavish is building a “Tesla of documents,” and waging war on bureaucracy, academia, and Big Tech along the way.

On Prof. Matan Gavish's left arm is a tattoo of a five-pointed star. "This is the orbit of Venus from the perspective of the Earth, a pentagram," he explains.

Why?

"We humans are sometimes subject to forces stronger than ourselves. The gods do whatever they want with mortals. Venus is a force that can capture your attention, redirect your desire toward something beautiful, attractive, interesting, and make you forget everything else. It is a force stronger than us, one that plays with us. I have that side in me. If I’m shown something interesting, I go all the way in, I dig into it until I come out the other side. But now I’ve committed to a mission of at least ten years, and I have obligations to investors, employees, and society. So I’m in negotiations with this entity, and I ask it not to turn my head elsewhere."

The meeting with Gavish (46), founder of the startup Factify, is unlike meetings with typical entrepreneurs, and certainly with professors - and not just because of the tattoos, earrings, and slightly hippie appearance of a world-renowned academic. During the interview, it feels as though several AI agents are running around in his head at once, as if his brain is bursting with ideas. Every touch of one idea opens a window to another, from which branches extend into an endless chain of information, unconventional thinking, and vivid answers filled with cultural, historical, and mythical references.

This is how, his students say, he taught the popular humanities course on the information revolution that he offered to computer science students before going on sabbatical to work on Factify. He illustrated it with examples from Greek mythology, the Bible, the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, Disney films, and the “Star Trek” series.

We meet at the company’s offices in a brightly lit building in the redeveloped garage district of south Tel Aviv. From here, he is trying to address a “dybbuk,” - a spirit - that has gripped him since his doctoral days at Stanford, which he completed in 2014: the feeling that the digital revolution has raced ahead and left the world of documents behind.

Gavish’s idea may sound somewhat dry and technical: eliminating form-filling for businesses in document-heavy industries using, of course, AI agents. The plan is to replace the outdated, static PDF format with a smart document that can “fill” itself out without human intervention in tedious, routine tasks. The concept may sound about as exciting as an accounting conference in Eilat, until Gavish paints it in vivid colors.

"The real revolution is bureaucracy that will no longer be handled by humans," he explains. "The goal is to free people from this inefficiency and burden, which significantly slows organizations down. There will no longer be paperwork, because automation will become an infrastructure layer."

How will this happen?

"The tools are smart documents that communicate with one another, know how to extract what they need from each other, and are easy for machines to process. Filling out documents is a tedious experience. How many times can I write my ID number and address? If forms are intelligent and know something about me, why can’t they fill themselves out? Maybe the form could call me and say, ‘Hello Matan, I’m your insurance renewal form. Has anything changed?’ Maybe I could ask all the valid contracts I’ve signed to ‘activate’ themselves. Why can’t my tax return submit itself? All the relevant paperwork already exists, it can find it. And why can’t receipts submit themselves to the tax authority, instead of me suffering the headache of collecting and totaling them?

"The analogy is Spotify. If I want to organize the best Bon Jovi songs, it happens in a second. I don’t have to go to a record store and search for every album. That’s how we should operate in the world of documents: if everything exists, even if it’s scattered, the data can organize itself. It’s a more advanced documentary experience. Everyone can imagine it, but it has to be built. It’s the automation of bureaucracy, and when it becomes fast, easy, and secure, it will change the economy."

When will the revolution happen?

"We’re already there in a small way, and we hope to become the leading method within five years, until it becomes almost absurd to do it the old way, and we become the standard."

Building a “Tesla” of documents

Investors were immediately fired up. Gavish recently completed a $63 million Seed round, an extraordinary amount for such an early-stage company. Factify was founded in 2023 and has only about 40 employees. The Seed round was preceded by an equally extraordinary $10.3 million pre-Seed round.

A lot of money for such an abstract idea.

"My idea isn’t abstract, it’s just huge."

Did venture capital funds even understand what you wanted to do?

"We first raised money in the spring of 2024, when interest rates were high and no one was writing checks. People told me, ‘Matan, get ready, it’s going to be long and humiliating.’ But in the end, it was short and great. I went to Silicon Valley and came back within 48 hours with $10 million for the pre-Seed stage. The team asked, ‘What did you do?’ I told them, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. I came back with twice the money I wanted in two days, and I’m already on the plane home.’"

What happened there?

"Silicon Valley is hungry for disruptive ideas that create new markets. They looked at the idea and said, ‘We get it.’"

And how did the Seed round go? Were you warned again about being humbled?

"I wasn’t planning to raise more money, the round came sooner than I expected and before we actually needed it."

So how did you complete an unplanned round?

"We started talking to customers and showing early versions of the product. The reactions were so enthusiastic that investors said, ‘If I don’t do this now, Sequoia will.’ Only six months passed between the pre-Seed and the start of the Seed round. But when investors you really value approach you with terms that are right for the company, you take it. It’s not complicated."

Does it really take that much money to develop the Factify product?

"Yes, because we’re building everything from scratch. How did they build Tesla? At first, many people tried to take a gasoline car and replace the engine with an electric motor. Then someone said, ‘We have to start from scratch: four wheels, a new battery architecture, and a very powerful computer.’ Tesla’s product is great because it owes nothing to the cars that came before it. The same goes for us. Our product is great because it owes nothing to what came before it. It doesn’t use anything that resembles a PDF form.

"Factify requires significant capital because we’ve invented a new database infrastructure, a new type of document with applications, a new user interface, and a new way of presenting documents to people. These are substantial systems being built from the ground up. In addition, we’re entering a field with very powerful incumbents, and we’ll likely disrupt them, so we need the resources to move quickly and effectively."

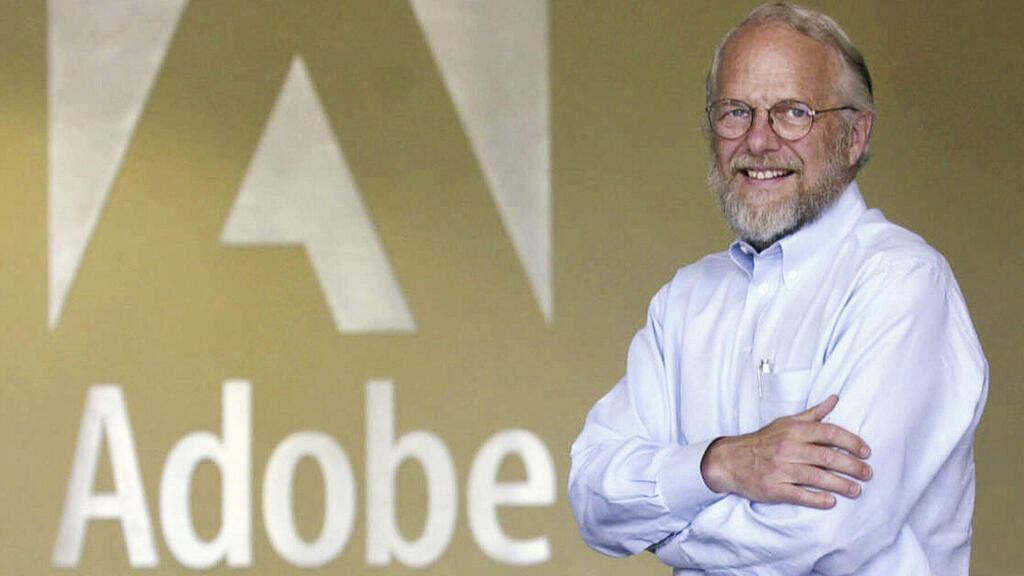

For example, the software giant Adobe, which, among other things, owns the PDF format?

"Yes. Adobe was built around the PDF, invented by its legendary CEO John Warnock, who passed away two years ago. We actually celebrate his birthday here, because he was a giant of the 1990s. What he did then, we want to do now. He was the last person who had the courage to say, ‘I am reinventing the document for everyone.’"

The current funding round was led by Valley Capital Partners. Prominent Silicon Valley figures also participated, including John Giannandrea (a former executive at Google and Apple), Ken Moelis (founder of the investment bank that bears his name), Peter Brown (CEO of Renaissance Technologies), and Shai Wininger, founder of Lemonade.

"The relationship between entrepreneurs and investors is delicate, and our relationship with our lead investors is exceptional," says Gavish. "They were an excellent choice, and they’re not Israeli. We were their first Israeli investment. Since then, now that they understand what an Israeli company is like, they’ve invested in three or four more Israeli companies."

How difficult was it to convince them to invest in a first-time entrepreneur like you? The trend today is to back experienced founders.

"Experience is very important. But when it comes to an entrepreneur for whom this is ‘their first child’, someone who imagines a new market and lives and breathes the company more than anyone else, you often prefer that person, even if they make mistakes. For me, it’s truly an obsession. I’m on a fascinating, all-consuming, and sometimes brutal journey."

What do you mean?

"When I say all-consuming, I mean working 18 hours a day, six days a week, for two years. Brutal because you have to learn constantly in a reality that changes very quickly, while managing expectations from investors, customers, and employees, and maintaining belief that something which doesn’t yet exist truly has a place in the world. Every day, every minute, there’s a fear of losing your investors’ money and not meeting their expectations. It’s a huge responsibility, and it demands that level of dedication. For something like this to come to fruition, someone has to be willing to take that risk personally."

At the Olympic academic field

Gavish grew up in Haifa, the son of a psychologist and an engineer, one of Intel’s first computer engineers in Israel. "I hated school. It was hard for me, and in high school I even wanted to drop out," he says. "I was a bit of an idealist and a bit bored. I graduated with mediocre grades. In the army, after dropping out of flight school, I became a paramedic instructor. But I was always rebellious, and original, creative thinking from an 18-year-old doesn’t fit well within a military system. The army needs people who do what they’re told and ask few questions, if any."

His academic path proved far more successful. Gavish earned a double bachelor’s degree in mathematics and physics in the outstanding students program at Tel Aviv University, completed a master’s degree in theoretical mathematics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2008, and went on to a prestigious doctoral program in Stanford’s Department of Statistics.

5 View gallery

Factify investors (rrom right, clockwise): Wininger, Moelis, Brown, Giannandrea

(Dor Malka, Jeff Chiu/AP, Betty Laura Zapata/Bloomberg, Grace Villamil, Wikipedia)

"The statistics department at Stanford is ranked first in the world. Its doctoral program has always been very small, admitting a class of about eight students from around the world each year. That’s like entering the Olympic arena. I had to finish first in my class for that to happen. Suddenly, I was studying alongside the smartest student in India, the smartest in China, the smartest in Canada, and that was it. I wish more Israelis would study there. It’s like going to the Vatican to study with the Pope. Silicon Valley was built around Stanford; people in those departments built much of what we use today. Google and Apple were founded just across the street, in the computer science building. In that sense, the place is the cradle of digital culture."

What was your PhD about?

"A mathematical theory of data science, explaining why and when familiar methods in data science actually work. I worked under a highly respected supervisor of international stature, David Donoho, probably one of the greatest data scientists alive today, a multidimensional genius who has won nearly every major award in the field. As fate would have it, I was his only PhD student for several years."

And where was the idea for Factify born?

"At the time, with the move to the cloud and the widespread adoption of the software-as-a-service model in organizations, it was clear to us that the digital revolution that transformed the entertainment and music industries would continue advancing. Netflix and Spotify shifted file-based industries, which struggled with piracy and complex pricing, to a streaming model. We assumed something similar would happen with documents. But it didn’t."

Then you started the company?

"When I returned from my PhD, I began working as a senior lecturer in computer science. I established a data science program and taught artificial intelligence. Like a good Jewish boy, I received tenure and, three years ago, a professorship. But these ideas never left me. Until I finally gave in to what felt like destiny, and in 2023 I decided to start a company. That’s what a life mission looks like."

And Factify was born.

"The biggest opportunity lies where the pain is greatest. And the pain is enormous in document-heavy industries, insurance, healthcare, banking, and others. I’ve never met anyone who enjoys working with documents. The digital revolution has advanced rapidly, from stock trading to Netflix, but document workflows haven’t meaningfully changed in 30 years. It was clear there was a large, neglected problem here. Replacing the PDF is just a byproduct."

Aren’t you afraid you’ll fail, that advanced technology won’t catch on?

"Failure is always a possibility. In its early years, a startup is always one step away from catastrophe. But we’re obsessed with ensuring that the documents of the future don’t look like the documents of the past. And we’ll do it gradually, so the change doesn’t feel scary, difficult, or threatening."

"It's harder than talking about an illness"

Gavish lives in Givat Ada. He is divorced and the father of three daughters (12, 14, and 15). His life was shaken by a long and difficult divorce process that began in 2015 and concluded only in 2022. "Don’t try this at home," he says. "I understand why, at certain levels of difficulty, some men don’t survive it. I’m talking about what they perceive as injustices in family courts when children are young, about financial strain, about painful custody battles. Many men are ashamed to talk about it. It’s easier for them to talk about serious illness than about divorce. Even now, it’s hard for me to discuss."

You’ve spent your life in elite academia, and divorce suddenly demands more basic life skills.

"That’s absolutely true. An academic career develops certain abilities, but it doesn’t necessarily cultivate strong social or emotional skills."

What were the consequences?

"My life was shattered into its smallest pieces. I found myself with no money, no friends, no family structure, feeling as though I have no future and no hope. It’s a total experience. Ten years ago, I didn’t look like I do today, I didn’t sound like I do today. I changed. I learned new things and became different. I discovered that as a professor and scientist, there were many basic things I didn’t know about myself, about how to live. I set out to explore them and discovered entirely new worlds. I wanted to understand why I do what I do, what my calling is. What is the thing I can do that has the greatest positive impact on my environment? These are questions people often push aside. For me, they emerged from a deep crisis and a very vulnerable sense of helplessness. I asked difficult questions and met people who taught me important lessons."

Did the statistics professor become a spiritual seeker?

"I discovered that the human experience is much broader than I thought. I met intelligent people who know how to live, people with original, non-mainstream worldviews. Some approaches that Western culture considers marginal or strange contain valuable insights. As a researcher, I explored them carefully and adopted what made sense. If you go to Pardes Hanna, you’ll meet many such people, and not all of them are charlatans. For me, it was about survival. It opened a door to another world, taught me to work with emotions, to breathe, to be present in my body. I also became stronger. I learned to fight."

Related articles:

- Factify raises $63 million in Seed funding to kill the PDF and build a new document standard for AI

- "The next wave of AI won't arrive with fireworks. It will be boring, and that is a good thing."

- "The gap in the global AI arms race lies in infrastructure, and that's exactly where the opportunity lies"

For example?

"I spend time in nature, practice physical disciplines, yoga, hypnotherapy, I trained in jiu-jitsu. It creates balance. You can’t live only in your head all the time. And I approached it rigorously, someone trained in math and physics doesn’t accept ‘that’s just how it is.’ I need to understand everything from first principles.

"And all of that helps, because starting a company requires all of me. Everything I know, everyone I know, everything I believe, all my ability to understand myself, solve problems independently, and grow. It’s like playing ten instruments at once. In yoga, for example, you learn that even during an emotional storm, you can calm yourself quickly and profoundly."

How do you live with a head constantly bursting with ideas?

"It’s not easy to live with ideas morning, noon, and night. Only at 40 did I realize not everyone experiences that. Insights and ideas never stop flowing, and I feel responsible for them."

Meaning?

"I can’t just ignore them. If I have an idea that feels significant, I want to write it, share it, build it. You can’t simply put an idea on a shelf."

That might conflict with the demands of being a CEO.

"As a CEO, you can’t hide behind ‘I knew I was weak.’ It becomes a laboratory for personal growth. Every flaw in your personality is amplified within the company, so it’s your responsibility to improve. The parts of me that don’t function well are shouting at me through a megaphone from seven in the morning. I can’t escape them. That’s good for someone committed to growth, but you have to know how to handle it.

"This is the most interesting job I’ve ever had. But like parenting, being a founder takes you quickly to the most vulnerable edges of your personality. The ‘child’ meets you exactly at your sensitive points. It’s so powerful that you look at it and ask: ‘How did you know?’"

"Academia hasn't woken up"

In academia, too, he believes change is necessary. That conviction led him to create a humanities course for computer science students that examines the problematic aspects of the technological revolution. "It’s important to inspire people to think about the meaning of what they’re doing," he says. "That’s far more important than technical courses. The added value of a university is to open your mind and challenge your values."

When did you come up with the idea for this course?

"Computer science was in peak demand, artificial intelligence was becoming increasingly prominent, and I began asking myself whether I was giving my students the right tools for this new world. The degree is highly technical, and what you learn in it is very narrow. I thought the training also needed to be humanistic. Otherwise, each screw in the machine may do an excellent job, but the machine as a whole could lead humanity toward disaster. I discovered that students were eager for this perspective, it genuinely interested them."

So should degree programs change?

"Urgently. We need to teach more imagination, creativity, responsibility, and ethics. Around 100,000 people in Israel, software developers, product managers, and their leaders, are driving the digital information revolution. Yet many operate within an engineering bubble, where economic incentives disconnect their work from its broader consequences. Those incentives can also encourage immoral or even harmful outcomes. Like a certain spyware company that no one thought its products would lead to people being dragged out of their beds at night and shot."

AI can cause harm as well.

"Exactly. So who is responsible? The person who trained the model? The one who collected the data? The one who wrote the code? The one who deployed it? In class, I show students a picture of half a Tesla smashed into a wall and ask who is responsible. It quickly becomes clear that the answer is complex, and that they need broader tools to think it through.

"In the context of my so-called ‘hippieness,’ I went through a process of expanding my perspective, which led me to ethical questions. In the end, everything connects. It’s reassuring to see that your life isn’t just a collection of random facts. And since we’re building technology that aims to strengthen truth, grant control, and respect privacy, I want to build a company, and hire engineers, with a strong ethical backbone."

Is it even worthwhile to study computer science today?

"Not in its current format. The degree does not adequately prepare students for the next generation of computer science. Historically, it grew out of mathematics, but someone who wants to specialize in artificial intelligence systems might benefit more from studying physics. Physics provides a deep understanding of models and systems. If I were choosing today, I might study physics alongside Carl Jung, to better understand the human psyche."

So the problem in academia is broader?

"Academia is in the midst of a dramatic transformation, and its leaders may not fully grasp it. The way students learn has changed, yet universities continue building physical campuses. Why? Many students barely come to campus anymore. Learning habits have fundamentally shifted, but academia hasn’t fully awakened to this reality. Why are lectures constantly recorded? I can guarantee that anything I can teach on camera, someone else in the world has already recorded better. Artificial intelligence is reshaping the very definition of what a professor is and what a scholar does. I sincerely hope academic leaders understand the magnitude of this moment."

So academic studies are unnecessary?

"The value of education lies in mentorship and skill-building, not just in delivering exercises and solutions. Saying ‘enrollment is up, so everything is fine’ is like being the Catholic Church in Europe in 1500, just before the Reformation."

What would doing it right look like?

"A more humanistic structure. Smaller learning groups. Fewer undergraduates. In humanities courses, for example, classes should revolve around discussions of material students study independently at home. That model works very well."

Not only academia, but also the high-tech job market is undergoing a revolution.

"Like much of Israeli high-tech, we don’t hire junior employees, because we develop artificial intelligence with the help of automated systems. So what do we need? Creative, mentally resilient people who can think outside the box, believe in an idea and then let it go when necessary. They must be able to work in teams at a fast pace and possess specific technical skills, not all of which are acquired in a traditional degree program."

Not only employees are affected, companies are as well. Some software companies, such as Wix or Monday, have been hit by the market shift.

"These companies were once valued at extremely high multiples that assumed hyper-fast growth. Now expectations are more moderate. Companies that traded at multiples of 100 or even 1,000 may now trade at 20 times earnings. That’s still a strong multiple, nothing catastrophic has happened. It simply reflects a more realistic understanding of which companies will become giants and which will not."

And all the AI hype could also backfire.

"In Disney’s ‘Fantasia,’ there’s a scene where Mickey Mouse, as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, orders a broom to carry water from a well. He falls asleep, and when he wakes up, the house is flooded. The broom kept carrying bucket after bucket because it was never given a stopping point. He smashes it, but the fragments turn into many smaller brooms, making the situation worse. Every technology is a kind of Faustian bargain. You gain something, but you give something in return, and you don’t always know what that will be. In a way, I was relieved that AI is the first technology to spark widespread discussion about its risks.

"Information technology can also be enslaving. Everything you say or do in the public sphere contributes to a digital profile of you. This could enable a form of digital totalitarianism that would make Orwell’s ‘1984’ seem naïve. You read Facebook, but it also reads you. Technology in the hands of regimes without checks and balances can be dangerous. And we haven’t seen the full extent yet.

"I make my students watch an episode of the series Black Mirror about social credit. In it, everyone has a contact lens that identifies the people they see and displays the average social rating others have given them. As a result, everyone behaves with exaggerated politeness, almost to the point of absurdity. It’s a difficult episode to watch, especially because it reflects facial recognition technologies that already exist.

“Anyone who has willingly uploaded thousands of photos of themselves to Facebook may find it’s already too late. Reclaiming their privacy would require something as extreme as changing the distance between their eyes. Good luck with that."