The calm town at the center of the quantum race

Lyngby has become Europe’s bid to avoid another technological defeat and secure sovereignty in the post-AI era.

The drive to Lyngby, a university town north of Copenhagen, creates a deceptive sense of calm. Nothing in the serene Scandinavian landscape hints that behind a cluster of modest buildings sits one of the most ambitious technological efforts ever undertaken outside the United States: an attempt to build an entirely new kind of quantum computer, one that could reshape not only computing but the global balance of power.

Microsoft’s Lyngby facility, built at an investment of more than one billion Danish kroner ($157 million) and developed in close collaboration with the University of Copenhagen and the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), blends seamlessly into its academic surroundings. From the outside, it looks like just another campus building. Inside, it is something else entirely.

At the heart of the facility stand the so-called “golden chandeliers” - the massive dilution refrigerators that have become icons of the global quantum race. Each descends roughly four meters and is built from layered copper and gold designed to cool quantum chips to temperatures approaching absolute zero. The nickname comes from their shape, but the work they perform is anything but decorative. It is an unforgiving battle against energy itself: every stray photon, every microscopic vibration, can disrupt a qubit, the fundamental unit of quantum computing.

In the quantum world, heat is not merely a nuisance; it is a fatal flaw. Even the smallest fluctuation can invalidate an entire calculation. Quantum chips are therefore lowered through successive cooling stages until they reach millikelvin temperatures, colder than outer space. In this environment, near total darkness, near absolute zero, qubits behave in ways that nature allows almost nowhere else.

A New State of Matter

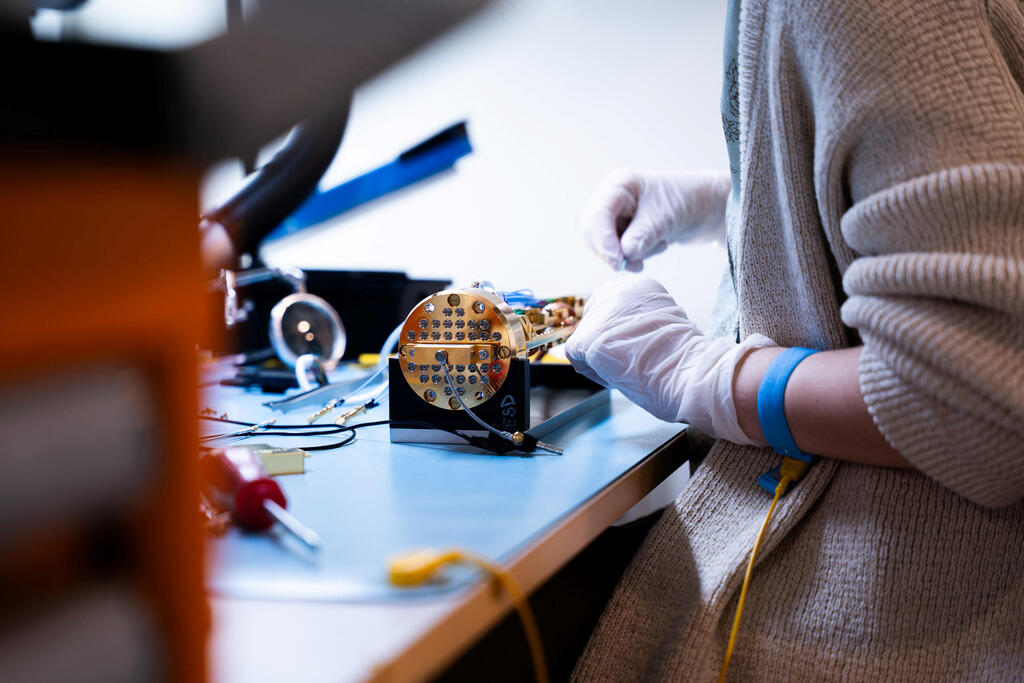

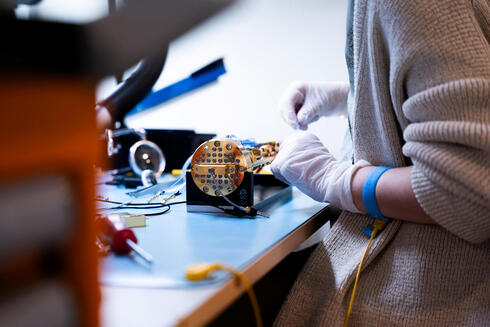

Beyond another sealed door lies one of the most remarkable spaces in the facility: the Fabrication Lab, known simply as “the fab.” It resembles a surgical theater of the semiconductor industry - sterile, silent, and unforgiving. But unlike conventional chip fabs, where engineers deposit metal layers or etch silicon, here researchers create something that until recently belonged to theoretical physics: a new state of matter.

Microsoft’s approach is based on topological qubits, which are inherently more stable than conventional qubits. Producing them requires a physical structure that does not occur naturally. Using Molecular Beam Epitaxy, ultra-high-vacuum systems that fire indium arsenide and aluminum atoms onto silicon wafers with atomic precision, engineers build the material layer by layer. The process resembles sculpture, but at the scale of particles. Each atomic layer must be flawless; a single defect can destroy the qubit’s stability.

The margin for error is vanishingly small. A grain of dust can ruin an entire chip. A misplaced molecule can alter a qubit’s behavior. This is why Lyngby has become a center for atomic-scale manufacturing, translating ideas that lived for decades in theoretical papers into physical reality. The result is Majorana 1, Microsoft’s new quantum processing unit, the first chip in the world to contain fully realized topological qubits, not partial demonstrations. The current version integrates eight qubits and is designed to scale, in theory, to as many as one million.

There Will Be No Second Chance

To understand the significance of Lyngby, it helps to step back and think at a continental level. Over the past three decades, Europe has accumulated a series of technological near-misses that have taken on an existential tone. It did not lead the internet revolution. It did not produce the dominant social platforms. It failed to control the smartphone supply chain. More recently, it has struggled to keep pace with AI advances driven by the United States and China.

Across Brussels, Copenhagen, and Berlin, the prevailing view is that quantum technology represents a final opportunity. This sense of urgency has given rise to the Quantum Europe Strategy, an effort to build an end-to-end ecosystem: basic research, national infrastructure, shared standards, and, crucially, technological sovereignty. Europe’s conclusion is stark: regulating technology is not enough. To retain strategic autonomy, it must own the core technologies themselves.

That ambition is expected to be reinforced by the forthcoming Quantum Act, slated for 2026. The legislation aims to create a new incentive framework, including public funding, shared infrastructure, support for materials and equipment manufacturing, and the protection of internal supply chains. Within Europe, quantum is now discussed in the same strategic terms as nuclear power was in the 1950s: not as a research discipline, but as national infrastructure.

Denmark, however, moved earlier. Rather than waiting for EU-wide funding, it built a hybrid model combining elite universities, public investment, capital from European institutions such as Novo Nordisk, and global industry, led by Microsoft. Initiatives like QuNorth seek to ensure that Europe does not merely publish quantum research, but manufactures quantum technology at scale.

A Doomsday Weapon and a Magic Wand

The stakes of the quantum race are extreme. A sufficiently powerful and stable quantum computer would function as both a doomsday weapon and a magic wand. On the security front, it could theoretically break RSA encryption within hours, rendering today’s internet traffic, banking systems, and state secrets defenseless. The balance of power would shift overnight.

The economic implications are equally profound. Quantum computing could enable the design of entirely new materials at the atomic level: drugs for neurodegenerative diseases, batteries that charge in seconds, fertilizers that dramatically increase crop yields. Control of quantum technology would confer not only economic leadership, but the ability to shape the pace of human progress itself. Europe’s determination not to leave this power solely in American or Chinese hands flows directly from this reality.

Denmark’s role is deliberate. What has made Lyngby attractive is not scale or spectacle, but stability. The facility was built for decades, not for a five-year funding cycle or a short-term corporate bet. The Danish government provided land, capital, regulatory clarity, and a culture of cooperation. The result is an ecosystem where international researchers can plan long careers and students gain daily exposure to frontier technologies.

The Danes emphasize another differentiator: openness. Unlike Silicon Valley’s culture of guarded secrecy, Lyngby operates on shared physical space and institutional collaboration among academia, government, and industry. Europe sees this model not as a weakness, but as a potential structural advantage.

A Continental Vision

At first glance, an American corporation anchoring Europe’s quantum ambitions appears contradictory. Microsoft argues otherwise. Its European leadership frames Lyngby as a genuine partnership, combining European scientific expertise with industrial engineering capabilities. The decision to manufacture the quantum core in Europe rather than the United States is, in itself, a strategic signal.

Microsoft has also linked the Danish lab to its advanced AI infrastructure in the cloud, creating a feedback loop in which data from materials experiments is fed directly into AI models that optimize manufacturing. This convergence accelerates progress in a way that neither field could achieve alone.

Ultimately, the significance of Lyngby lies not in its refrigerators, vacuum chambers, or chips, but in the decisions behind them: Europe’s decision not to relinquish the next foundational technology; Denmark’s decision to invest in long-term infrastructure; and Microsoft’s decision to transform theoretical physics into manufacturable reality. Beneath Lyngby’s quiet exterior lies a continental bet on the future. If it succeeds, the history of computing may indeed be divided into two eras: before Lyngby, and after.

The author was a guest of Microsoft at the Quantum Lab in Lyngby.